Caught in Facebook’s net

Will its increasingly complex website be its undoing?

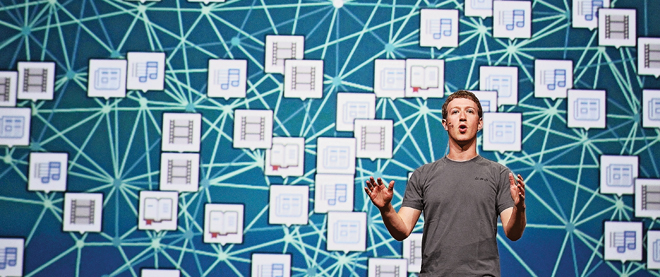

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Share

Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of social networking giant Facebook, stepped onstage at a developers’ conference in San Francisco last week and, probably unwittingly, launched into his best Steve Jobs impression. Wearing jeans, sneakers and a grey T-shirt (the Apple Inc. chair favours black turtlenecks, but you get the idea), Zuckerberg took the wraps off a host of new Facebook features while peppering the presentation with Jobs-isms—“really easy” yet “so powerful”—that emphasized just how intuitive and exciting everything about the overhauled Facebook would be.

Except that none of the new features unveiled appear to be either—at least not at first blush. Once a relatively spartan piece of online real estate, users’ profile pages will now display a comprehensive “timeline” of their lives, curated in part by Facebook’s software and by users themselves, while a new window shows exactly what everyone in your network is doing at any given moment (Stephanie likes Peter’s status update, Lisa commented on her photo, Steve is friends with Sharon . . . and so on). Zuckerberg called it a place to monitor “lightweight” activity that threatens to bog down the main news feed, which will now consist entirely of material that is deliberately posted by a user’s friends.

Turns out there’s a reason Facebook decided to create a dedicated space for all of these auto-updates: it plans to unleash a torrent of them on its users. The company is planning to throw TV, streaming music and other online media services into the mix so that users can see, in real time, what songs their friends are listening to, which TV shows they’re watching and what news stories they are reading—and soon, no doubt, where they’re shopping. “What’s even more interesting and exciting than getting people signed up is all the things that are possible by having these connections in place,” said Zuckerberg, who suggested that Facebook and its partners will “rethink some industries.”

What, exactly, is driving all this change? It’s not Facebook’s 750 million users, some of whom complained loudly last week when a few tweaks were rolled out in advance of the conference. Instead, it has more to do with ongoing efforts to transform the Internet phenomenon into a cash-producing business. Zuckerberg knows Facebook must continue to evolve if it’s to stay ahead of rivals like Google Inc. But can he do it without sacrificing the very thing—a simple way to stay connected with friends—that made Facebook a hit in the first place?

From a numbers standpoint, Facebook’s foray into online music and video is a no-brainer. The amount of video that Internet users watch online continues to balloon, with Google’s YouTube leading the pack with 162 million unique viewers in August, according to research firm ComScore. Facebook, meanwhile, was in third place with 51.6 million viewers (although many Facebook users view YouTube and other online video content via links on Facebook posted by their friends).

More importantly, making Facebook an online media hub promises to further solidify the site’s emerging position as people’s gateway to the Internet, similar to the way that Yahoo! was in the 1990s and Google in the last decade. But with one key difference. While Web users may start their surfing on Google’s clean-looking home page, they tend to use it as a springboard to other websites. But on Facebook, people are encouraged to stay in one place. ComScore numbers show that visitors to Facebook spent an average of more than seven hours on the site in August, more than any other site. “The changes we made last week ensure the level of engagement and passion for Facebook,” said Carolyn Everson, Facebook’s vice-president of global marketing solutions, in an interview with Maclean’s. “It’s moved from a place where people would post their updates to a place that literally is a container of their lives.”

Since advertisers follow eyeballs, keeping Facebook relevant and engaging users translates directly into increased sales. Research firm EMarketer Inc. estimates that Facebook, which is privately held, is on track to generate US$4.27 billion this year, about double 2010 (Everson declined to comment). And that’s just the beginning. The global market for brand advertising is worth about US$650 billion, much of which currently flows into the pockets of the television industry. But Facebook, a company developed by Zuckerberg in his Harvard dorm room just seven years ago, is betting it can grab a big slice of the market, which is why some are now valuing the company as high as US$100 billion.

Encouraging users to share their personal information is also key to Facebook’s long-term success. People in the industry now talk about “Zuck’s law,” which states that Facebook users double the amount of information they share each year. Everson says that, for advertisers, this provides an unparalleled opportunity to achieve word-of-mouth advertising—the most influential kind—on a massive scale.

At present, the majority of interaction between Facebook users and corporations takes place on companies’ Facebook pages, where users can voluntarily join as “fans” (companies also advertise on users’ home pages, often by offering games or contests that are designed to draw people to the company’s Facebook page). But it’s not just these people who are being reached by advertisers on Facebook. A recent study by ComScore found that friends of “fans” of Southwest Airlines, for example, were 2.5 times more likely to visit the airline’s website than the average Internet user. Justin Merickel, the vice-president of marketing for Efficient Frontier, a California-based online marketing company, says this is the true power of social networks when it comes to advertising. “You don’t have the emotional television spots, but what I think Facebook does have, and what they are leveraging, is their core product: connections.”

It’s all potentially bad news for Google, the current king of online advertising. Fearing a future where Internet users spend the majority of their time on Facebook, the search giant rolled out its Google+ social networking platform earlier this year and managed to rack up some 25 million test users before opening up its site to the masses last week. Tech bloggers have lauded Google for building in new features, such as a nifty way to sort friends into different “circles” so users can control who they share information with, and a feature called “hangouts,” a novel take on group video chats that switches webcams based on who’s talking. Though few people expect Google to seriously threaten Facebook’s dominance (Zuckerberg noted during last week’s keynote that as many as 500 million people have logged into Facebook in a single day), the early gains made by Google+ have suggested that it’s certainly possible to improve the social networking experience. “It’s going to be hard for someone to erode what they’ve built,” Merickel says of Facebook. “But that’s not to say it’s game over and they’re the winner.”

The risk is that as Facebook takes steps to maintain its hegemony, it may inadvertently end up trying to be too many things to too many people. One of the key reasons Facebook triumphed over MySpace was its simplicity. It didn’t get bogged down with cluttered profile pages, running media players and other extras—until now. It’s the same trap that Yahoo! fell into more than a decade ago as its portal strategy yielded a website riddled with buttons and links, which stood in stark contrast to Google’s stripped-down search engine. “The same truth applies in 2011 that applied in 1997,” says Carmi Levy, a Canadian independent technology analyst. “It’s all about getting as many users as possible to spend as much time on your site. Software service type companies like Facebook and Google walk a thin, high wire as they decide how many features to incorporate in their services and how complex the interfaces should be.”

Zuckerberg, on the other hand, seems to believe he can safely continue to add new features and functionality so long as it encourages users to share more personal information. He likes to point out, for example, that Facebook’s introduction of its news feed feature in 2006 resulted in howls of complaints from users who viewed it as unnecessary clutter. It has since become Facebook’s most popular feature. So while “Zuck’s law” may explain the exponential increase in sharing taking place on Facebook, Zuckerberg’s real brilliance may be recognizing the value of swapping trivial personal details in the first place: the more of your life is uploaded to Facebook, the more difficult it becomes to pick up and leave. No matter how hectic it gets.