Encyclopedia of the oil crash: R is for Russia

…and recession, reserves, and royalties. View this and more in our encyclopedia of the oil crash

Share

RECESSION (ALBERTA, 1980s)

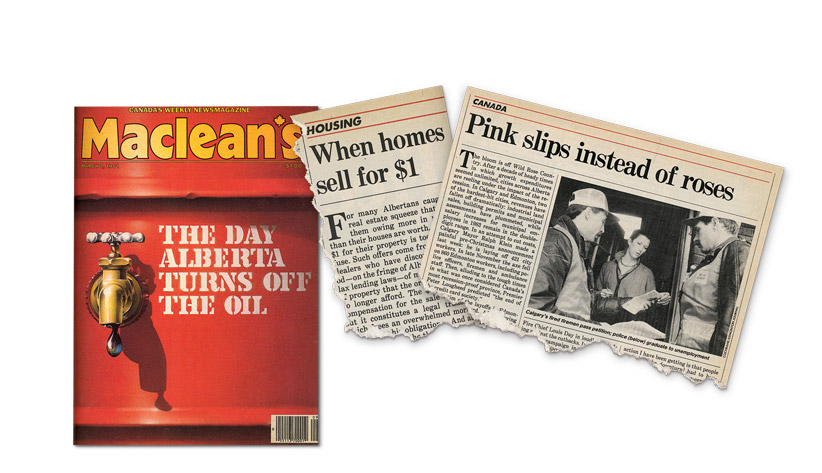

The year 1981 would mark the end of the eight-year oil boom. Two years later, as Maclean’s reported at the time, Alberta was struggling with a double-digit unemployment rate and a housing crash that had led to a crush of foreclosures—and people selling homes for absurdly low prices in order to get out from beneath massive mortgages.

RECESSION (2008)

We’ve seen this movie before. In July 2008, the price of oil peaked at US$145 a barrel, before tumbling all the way down to $30 and change just before Christmas. But the doldrums didn’t last long. By the next spring, crude was already back bouncing around the $70 mark. And the $100-plus boom times returned in early 2011. Albertans, and Canadians as a whole, should be pulling for a similar V-shaped price curve this time around, for that helped to pull the country out of the “Great Recession.” Driven by international demand for oil and other commodities, the Canadian economy was back growing after just two quarters and, within two years, had made up for all the jobs lost in the Great Recession—a better performance than any other G7 nation, as the Harper government never tires of reminding us. (Alberta’s comeback was even more spectacular. Provincial unemployment, which peaked at 7.7 per cent in the summer of 2009, was back under five per cent by the beginning of 2012. And, as of early 2014, the province was responsible for 90 per cent of all new jobs being created in the country.) Will the sequel play out the same? Oil’s current free fall—from $108 a barrel in June to $46 in mid-January—hasn’t been quite as precipitous as the last one. On the other hand, by this time, the V-shaped rebound had already begun. Jonathon Gatehouse

[widgets_on_pages id=”A to Z of the Oil Crash”]

RECESSION (WILL WE HAVE ANOTHER?)

We asked economists: Could the oil crash lead to another recession in Alberta? How about Canada?

Randall Bartlett, TD Economics

Randall Bartlett, TD Economics

On Alberta: What we’re expecting to see is that Alberta’s growth will remain in positive territory on an annual basis, but it is going to be dramatically weaker than even what we were expecting back in December. It’s certainly going to feel like a recession, but we don’t think it’s going to dip into negative territory.

On Canada: We definitely don’t see that happening in Canada. Lower oil prices do have a net negative impact on the Canadian economy, both in real output and income, but that part of the negative impact is going to be balanced or offset by positive economic impacts to non-energy producing provinces, such as Ontario.

Robert Kavcic, BMO Capital Markets

On Alberta: In theory, yes, we’ve revised down our forecast for 2015 to 0.5 per cent. If not technically a recession, it’s probably as close as you’re going to get to one.

On Canada: Probably not. From what we’ve estimated, the impact is probably, at most, half a percentage point cut to economic growth.

On Alberta: It won’t be a huge surprise to see some negative quarters for the Alberta economy during the temporary lull in oil prices. We tend to think of recession as 10 per cent unemployment rates, but, when you start from such a low unemployment rate (4.7 per cent), you may end up with a period that qualifies as a recession, with still relatively mild unemployment and a healthy provincial balance sheet.

On Canada: Very unlikely. It’s negative for the national economy, but, unless the fall in oil is associated with recessions elsewhere in the world, we’re just likely to see a period of disappointing growth.

Pedro Antunes, Conference Board of Canada

On Alberta: We believe it will be very hard for Alberta to avert a recession, in that we’re taking so much out of that economy, all in one shot.

On Canada: Not a recession, no. But, not that long ago, an oil price shock like this would have been good for Canada, because we weren’t that big an energy producer. Today, Canada is a much bigger crude producer and it’s going to be hard to overcome the negative impacts to some key provinces with the positives that are happening elsewhere.

On Alberta: It’s certainly not out of the question. If, in another three months, these oil prices haven’t recovered at all, or if they’re even lower, we would reduce our forecast for growth to something even weaker. We still believe the most likely scenario is Alberta will avoid an outright contraction this year.

On Canada: Because the U.S. economy is picking up and our dollar is soft, I think it’s less likely that we would see a Canadian recession stemming from the downturn in oil.

On Alberta: Yes, if the current prices are sustained. Our view is that we won’t see prices sustained at these levels. As oil picks up, we should avoid a recession in Alberta.

On Canada: No. When you take the negatives, then look at some of the offsets [cheaper gasoline and a lower dollar], we think it comes out as neutral for Canada as a whole.

RESERVES (UNRECOVERABLE?)

Calculating a nation’s oil reserves used to be a matter of figuring out how much crude could be recovered commercially, given current prices and technology. But, increasingly, it looks like the impact on global greenhouse-gas emissions could play a role in the calculation, too. Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England (and the former head of Canada’s central bank) has suggested the “vast majority” of the world’s fossil fuel reserves could be rendered “unburnable” if the world is to avoid catastrophic climate change. For Canada, that would have the effect of rewinding the clock 30 years by locking the estimated 170 billion barrels of oil sands crude in the ground. Chris Sorensen

ROYALTIES

University of Alberta economist Andrew Leach dissects what falling oil will mean to the royalties Alberta collects from the industry:

Low prices affect both the royalty rate, since Alberta uses a sliding scale, and the base on which royalties are collected—so Alberta is collecting (in some cases) a smaller share of a smaller pie with low prices. In its budget documents, Alberta Finance assesses sensitivities to changes in oil and gas prices. It calculates that a $1 drop in the oil price has a $215-million impact on revenues, a 10-cent drop in the gas price affects the budget by $8 million, and a one-cent depreciation in the Canadian dollar increases revenues by $241 million.

The budget in 2014 was based on West Texas Intermediate oil at $US95.22 and Western Canadian Select oil at $77.18, with a 91-cent Canadian dollar. If prices continue at their current levels, WTI prices will end the fiscal year at an average of a little over US$80 per barrel, which would be about a $3-billion hit, if you simply use the sensitivities in the budget, but, for major drops in prices, the percentage drop in taxes and royalties could be larger, as profits drop proportionally by more. The Canadian dollar provides some help, but not as much as you might think, as it will average just under 89 cents for the year, if rates stay at today’s level—only 2 cents under the budget figure, but still likely enough to make up close to half a billion of the lost royalties. Gas prices are a little above forecast, on pace to average $3.62 for the year versus a forecast of $3.29, so that will provide a small increase on the order of $25 million. Premier Jim Prentice has suggested that Alberta is on pace to see a small deficit, rather than the forecast $1.5-billion surplus. My back-of-the-envelope calculations above would suggest a deficit closer to $2 billion, if prices don’t bounce back in the next 10 weeks.

RUSSIA

Russian President Vladimir Putin lived by oil—and he’ll be damned if he’s going to die by it. Putin’s legacy in Russia so far rests on the transformation the country underwent during his first two terms as president, from 2000 to 2008. Russians remember the presidency of his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin, as a time of economic decline and instability. Under Putin, pensions were paid, salaries increased and sense of self-worth returned. He owes much of this to the high price of oil at the time. It was a fragile pedestal on which to stand, and he knew it. “He’s been working very hard to develop other bases of legitimacy, a legitimacy based on connecting with the Russian people,” says Seva Gunitsky, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Toronto. “Obviously, foreign policy is a part of that.”

This means that, as Russia’s economy suffers from the combined effects of Western sanctions and plummeting oil prices, Putin can point to Russia’s annexation of the Ukrainian region of Crimea, and its ongoing, if unacknowledged, military intervention in eastern Ukraine, as proof that Russia remains strong. Both moves have been broadly popular among Russians, who are again feeling the effects of the Kremlin’s shrinking revenue stream.

Some worry that Putin will now be tempted to double-down on foreign adventurism as a tactic to bolster his domestic support. This would be risky, says Mark N. Katz, a professor of government and politics at George Mason University. “The trouble with getting involved in more conflicts is that if he doesn’t win immediately, they can become very costly and draining, and he has fewer resources. So does he really want to do that? The drop in oil prices makes it very hard for him to lash out.” Already, Russian actions in Ukraine are a drain on Moscow’s budget. Much more blatant aggression risks triggering additional sanctions. But Putin can no longer count on as much oil and gas money to buy political popularity. He may be willing to gamble. Michael Petrou

NEXT:

S is for short Canada, Steyer, stock market, Suncor, supercycle, superpower

T is for tar sands, two-track economy

U is for upgrader debate