Has Ben Bernanke made Stephen Poloz’s job more difficult?

The Federal Reserve chairman and the Canadian dollar

Share

In normal times, conducting monetary policy is a combination of setting short-term interest rates and managing expectations about the future. But when interest rates are so low that the zero lower bound becomes a binding constraint, monetary policy becomes less a matter of what the central bank is doing now and more a matter of communicating what the central bank is planning to do over the next few years.

The yield curve is a good way of illustrating the role of expectations. According to the pure expectations hypothesis, long-term interest rates are set equal to the average of the short-term rates: for example, the six-month rate would be set equal to the average of the next six expected monthly interest rates. This is almost never the case; other factors such as risk and liquidity will generate deviations from what the simple model predicts. But it’s still the case that changes in longer-term interest rates are largely driven by changes in expectations. So short-term changes in the yield curve — that is, the relationship between interest rates and the duration for which they apply — are typically driven by short-term changes in expectations about the future.

If a central bank wants lower long-term interest rates, it’s not enough to simply promise to keep future short-term interest rates low: talk is cheap. Promises have to be credible, and one of the more effective ways to make believable promises is to establish a history of making good on your promises. So it was a good thing for the Bank of Canada that it had accumulated some 15 years of credibility in carrying out its inflation-targeting mandate when the crisis hit.

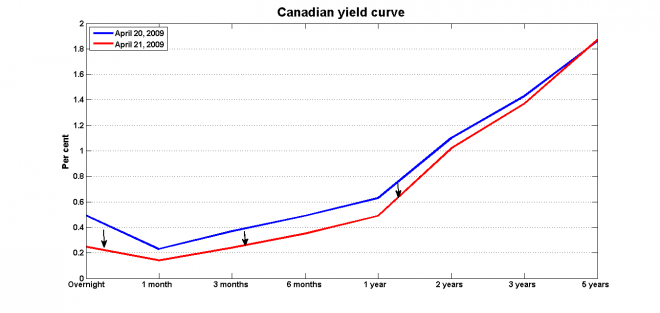

On April 21, 2009, the Bank of Canada lowered its policy rate to its lower bound, and it accompanied this measure with a ‘conditional commitment‘ to keep the policy rate at its lower bound until at least the end of the second quarter of 2010. The Bank’s goal was to generate a downward revision of future expected short-term interest rates, and it was largely successful:

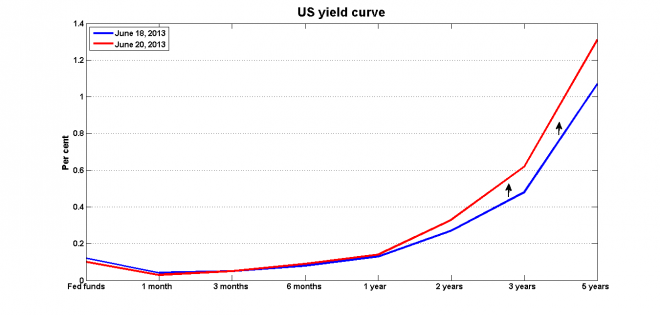

The Bank of Canada’s ‘conditional commitment’ announcement is a good example of a successful exercise in central bank communication. Which brings us to the remarks made by Ben Bernanke on June 19. It’s reasonably clear from the text of his remarks that Bernanke was not trying to bring about an upwards shift in the U.S. yield curve, and Fed officials have since confirmed that this was not what the Fed wanted. But the simple fact of mentioning what might seem to be obvious — at some point, the Federal Reserve would eventually wind up its asset purchases — appears to have been interpreted as an announcement that the Fed would stop buying assets soon:

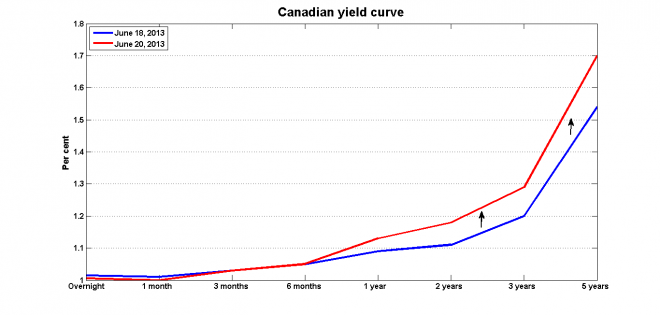

But look what happened in Canada:

There are two plausible reasons why Canada’s yield curve shifted up:

- Investors are idiots. This wouldn’t be the first time that markets seemed to be unaware of the fact that Canada has its own currency and that Ben Bernanake is not in charge of Canadian monetary policy.

- Developments elsewhere — particularly in China — are shifting yield curves up everywhere.

These explanations are not mutually exclusive. Either way, this is not a development that the Bank of Canada is likely to welcome. The associated decline in the value of the Canadian dollar — the CAD is down about 0.03 USD since June 19 — may or may not be enough to offset the increase in long-term rates.

There’s a French expression: manquer une occasion de se taire: “to miss an opportunity to keep quiet.” Stephen Poloz is unlikely to actually suggest that Bernanke missed a chance to shut up, but he might be forgiven for thinking it.