Can Canada Post survive the digital era?

Even radical reform might not save the post office now

Steve Russell/Toronto Star

Share

Update: On Dec. 11, Canada Post announced that it will phase out home delivery in urban centres. This feature by Charlie Gillis from March 2013 considers what the post office is up against:

As if Canada Post didn’t have enough problems. In the thick of a $2-billion modernization—with the Internet swallowing an ever-greater share of its lunch—came word that counterfeit stamps have been costing the 156-year-old institution an estimated $10 million in revenue each year. The new self-sticking stamps turn out to be a lot easier to fake than the kind you lick, postal officials acknowledged. “Our job is to detect and dismantle the network,” a spokeswoman said, “to really go for the big organizations.” But to anyone outside the postal world, enforcement problems raised by the story took a back seat to socio-cultural questions: who’s still sending letters these days—and so many that they need to forge stamps?

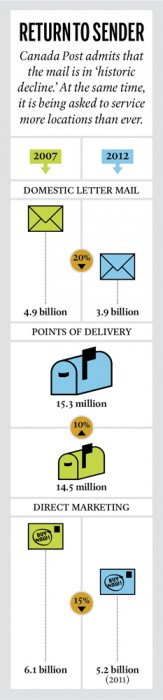

You don’t have to be a futurist to know snail mail is on the decline. Since 2006, the amount of domestic letter mail delivered annually by Canada Post has fallen by more than one billion pieces, a 20 per cent slide that has cast one of the country’s cornerstone institutions into existential crisis. Its once lucrative “direct marketing” business—junk mail—has fallen off by nearly 15 per cent, while its share of the parcel business has flatlined in the face of competition from private courier companies, many of which had partnered with online retailers. (Canada Post’s own parcel service recovered a bit last year; more on that later.)

The reasons are plain enough: like everyone else in the developed world, Canadians have been shifting their lives online, paying bills over the web, emailing loved ones rather than tossing a card into the post. Until recently, this shift was occurring at an orderly pace. In the early 2000s, volumes were holding steady and Canada Post was able to compensate for any losses by raising postage rates and cutting costs. The company remained profitable until 2011, when a 25-day labour disruption, combined with a court decision on pay equity, resulted in its first-ever loss.

But in recent months, the slide has accelerated, reviving long-standing fears about the post office’s ability to survive in the digital era. The company is on track to report another annual loss for 2012, and this time, the shortfall is due entirely to declining business. Letter mail, the bread-and-butter business that generates more than half of Canada Post’s revenue, fell off 6.4 per cent last year—a stomach-churning drop in a service over which it has a government-protected monopoly. The 273-million-letter nosedive accounts for nearly one-third of the post office’s volume losses in the past five years, and has left the company in a state of grim resignation. “There’s no question that mail is in a historic decline,” says Jon Hamilton, Canada Post’s general manager of communications. “We’re well-positioned for growth in e-commerce. But people buying a few things online is not going to make up for the mailbox full of mail we were used to delivering every single day.”

The question is: what will? The answer could determine the shape and size of the Canada Post to come—or whether there will be a Canada Post at all. In 2007, the pro-business C.D. Howe Institute published a study calling for the privatization of the postal service, along with deregulation that would allow competitors to deliver to its mailbox sites. Such a move would have left the post office to fend for itself or perish, possibly surrendering access to its own sorting facilities. But the idea gained little traction: as a self-supporting Crown corporation, Canada Post was returning a modest dividend to Ottawa each year, while costing taxpayers nothing in the form of direct subsidies from the federal government. Neither MPs nor voters saw much point in upsetting the status quo.

A year later, a strategic review commissioned by the federal government rejected privatization in favour of a wholesale modernization of the company. The arm’s-length panel recommended an ambitious upgrade of Canada Post’s decrepit sorting plants, financed by $2 billion in government-backed debt, along with a rethink of the service’s cumbersome logistics regime, which saw several workers handling mail in the same neighbourhood over the course of a single day—some dropping off mail at lock-boxes, others delivering to homes, still others delivering parcels.

The result can be seen in the so-called “transformation” initiative the company now touts at every opportunity. Small, multi-purpose electric vans now allow individual letter carriers to take mail—sorted and sequenced by address—from plant to neighbourhood doorsteps. In many places, the trucks swing through twice a day, says Hamilton, which has allowed the company to better compete with couriers: its parcel-post business grew seven per cent in the first three-quarters of 2012 compared to the same period last year. (Purolator, a courier Canada Post bought in 1993, operates separately and accounts for about 20 of the group’s revenue.)

Meantime, the post office has been amping up its online presence, partnering with retailers like Wal-Mart and Mountain Equipment Co-op to provide parcel delivery, and promoting its ePost service, which allows consumers to organize and pay bills through a secure Internet portal.

Yet even when it’s done, the transformation might not be enough to stave off wrenching change faced by post offices around the world. Last year, the U.S. Postal Service lost a record $16 billion and eliminated its time-honoured Saturday delivery service. The Netherlands and Germany have experimented with full or partial privatization of mail service, while New Zealand restructured its publicly owned post office to function like a private company, meaning it must cover its own losses and underwrite its own debt.

Robert Campbell, the author of a 2002 book on fixing postal services, led the review panel that recommended against the privatization of Canada Post. He says he suggested the reprieve, not as a permanent state of affairs, but as a temporary measure allowing the postal service to restructure to a new world of competition. “You’ve got what is basically a smokestack industry here that’s trying to modernize,” says Campbell, currently the president of Mount Allison University in Sackville, N.B. “It has huge legacy costs.”

Chief among its burdens: a $4-billion pension liability owed to current and retired employees that could hobble it in the face of leaner, private-sector competitors. Ottawa owes Canada Post the time—and possibly the financial assistance—to deal with that overhead before opening the field to its rivals, Campbell argues.

But if current trends hold, the pressure will rise, he acknowledges. This year’s loss reflects the gravity of Canada Post’s dilemma, and a few more like it could lose the company its prized status as a “self-sufficient” Crown corporation, meaning the government would have greater oversight of its managers and its board. Alternatively, Ottawa might simply proceed with deregulation, in the hope the market would provide cost-efficient substitutes to perform the same service. And that, in turn, would unleash a packet of new problems. What would happen to Canada Post’s obligation, enshrined in law, to provide universal service? Who would bring mail to rural and remote communities? Who would pay for it?

How close Canada Post is to that day is hard to say. Steven Fletcher, the minister of transport with responsibility for the postal service, said in an emailed response that the government will “work with Canada Post to ensure they are able to continue providing service to Canadians in a way that is sustainable in the long term without becoming a burden on the taxpayer.” But he didn’t say whether that might mean privatization or deregulation. And if Fletcher doesn’t see a more crowded playing field on the company’s horizon, he’s the only one. Even the head of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, which represents 54,000 employees, believes the future of the post office lies in robust competitiveness. The “exclusive privilege” to deliver letters is going down, says Denis Lemelin, noting that his members have accepted a lower wage for new hires in its most recent settlements. “You have to go into competition with private companies like FedEx and United Parcel Service. ”

Still, change may prove painful, for mail customers as well as postal workers. Even as Lemelin talks up the need to compete, his union is waging a court battle over allegations the current restructuring has placed unacceptable physical demands on workers. And Campbell wonders whether a reformed Canada Post might someday be forced to introduce differentiated pricing to reflect the high cost of getting mail to rural communities—a political land mine if ever there was one. Either way, he says, the chance of a publicly owned post service, modernized and maintaining the current level of service, is a long shot, at best. “I believe that’s what Canadians want, and Canada Post is giving it the old college try,” he says. “But it’s going to be an extraordinary struggle.”