Newsmakers 2015: Noel Biderman, the fallen king of infidelity

The hack that brought down Ashley Madison and its CEO only revealed a dirtier secret at the company

Noel Biderman, chief executive of Avid Life Media Inc., which operates AshleyMadison.com., poses by a hotel room window overlooking the Imperial Palace grounds during a photo session in Tokyo. Biderman is stepping down in the wake of the massive breach of the company’s computer systems and outing of millions of its members, Avid Life Media announced, Friday, Aug. 28, 2015. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko, File)

Share

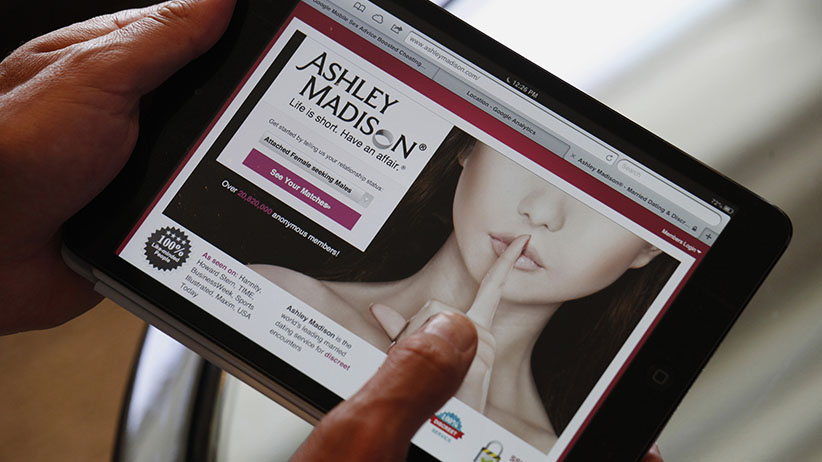

Noel Biderman is quite possibly the business world’s least sympathetic victim. The founder of marital infidelity website AshleyMadison.com—the homepage features a married woman (she’s wearing a wedding band) pressing a slender index finger to pouty, red lips—was brought down by hackers who exposed the identities of millions of would-be cheaters. Yet, to this day, it’s difficult to know what ultimately did more damage to Biderman’s “King of Infidelity” reputation—the fact he couldn’t protect his sheepish customers’ personal data, or the realization that Ashley Madison, despite its racy marketing, was revealed to be a bunch of horny men paying to flip through profiles of women who probably didn’t exist.

Before his world imploded, Biderman had managed to turn Ashley Madison into a $100-million company by charging (mostly) male members when they wanted to initiate contact with others on the site. Often banned from advertising in the usual places—television networks, subway cars—Biderman capitalized on the site’s notoriety by appearing on dozens of talk shows in Canada and the United States. On air, he defended Ashley Madison, launched a decade ago, by noting that cheaters were going to cheat with or without his service. “I’m not going to convince anyone to have an affair, with a 30-second commercial,” he once told Tyra Banks on her daytime program. “What I’m saying is if you’re going to have an affair . . . don’t do it in the workplace and, sure as heck, don’t go onto a singles dating site and lie about your status.” A heavy-looking gentleman in the audience, who had apparently been cheated on by his spouse, captured the mood of many in the studio when he blurted out: “How would you like me to come up there and kick your ass?”

Violence, of course, wasn’t necessary to bring down Ashley Madison. Its middling IT security saw to that. In mid-July, a shadowy hacker group calling itself the “Impact Team” claimed to have infiltrated the database of Ashley Madison parent company Avid Life Media. The group, angered by a $19 delete-profile service that apparently didn’t do what it promised, demanded Ashley Madison be taken offline immediately or else have details about its 37 million users posted online.

Avid Life called the threat “cyberterrorism” and assured users it had contacted police. But it was already too late. The hackers made good on their promise a month later, posting names, emails, street addresses and other identifying information about Ashley Madison users online. Several high-profile people were outed, including politicians, a Florida state prosecutor and the head of a prominent U.S. family values group.

The scandal, which came just as Avid Life was contemplating an initial public offering in the United Kingdom (due to investor queasiness in North America), prompted a larger debate about the ethics of exposing people who had committed no crime. Experts also pointed out that, thanks to Ashley Madison’s flimsy verification tools, email addresses couldn’t definitively be linked with actual people. “I could have created an account at Ashley Madison with the address of [email protected], but it wouldn’t have meant that Obama was a user of the site,” noted security researcher Graham Cluley in a blog post.

Equally damning was the revelation that the vast majority of profiles on the website belonged to men. In fact, by some counts, only about 12,000 of the site’s 5.5 million female profiles belonged to actual women. The rest appeared to be fakes created by Ashley Madison’s web team. In other words, it was a far cry from the carnal world depicted in Ashley Madison’s controversial marketing, and by Biderman himself. “There’s no word for a male mistress, but we’d better find one,” he said coyly during a CNBC interview a few months before the scandal broke—no doubt trying to lure even more paying male customers.

Biderman finally stepped down as CEO in late August. He was an infidelity king felled not so much by moral rebellion, but his website’s glaring inadequacies—not the least of which was its surprising inability to keep a secret.

[widgets_on_pages id=”2015Newsmakers”]