The death of the department store (1796-2017)

They were once temples of commerce and hubs of cultural activity. But rising competition, then the internet, rendered them irrelevant.

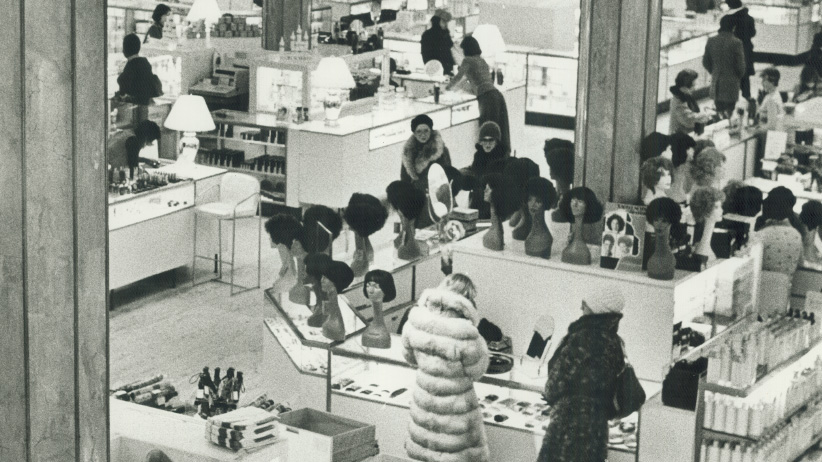

Eaton’s Closing in Toronto, Ontario, January 19, 1977. (Reg Innell/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

In 1796, a company called Harding, Howell & Co. opened the Grand Fashionable Magazine in London. It was an upscale shop that catered to women, who could socialize free of male chaperones, and was divided into sections offering furs, hand fans, haberdashery, jewellery, clocks and hats. The shop may well be considered the first department store, though it was a few decades ahead of its time. The true department store era didn’t begin until well into the 1800s, with the founding of Le Bon Marché in Paris, Harrods in London and R.H. Macy & Co. in the U.S. In Canada, the era was defined by three names—Eaton’s, Simpson’s and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The concept evolved in Canada from the trading posts and general stores that dotted the landscape, and was borne by a few converging trends: mass production, urbanization, rising disposable income and more efficient global trade owing to steamships and rail. Timothy Eaton, an immigrant from what’s now Northern Ireland, opened his first department store in Toronto in 1883. So tied was his business to the city’s railway workers that Eaton’s established regular sales on Fridays, knowing that workers were paid on Thursday evenings.

READ: Canada’s 10 most trusted brands

Department stores were different from anything Canadians had seen. The buildings were sprawling, multi-storey architectural marvels incorporating novel technology, such as electric lighting. Harry Gordon Selfridge, the founder of Selfridges in London, is said to have declared that “a store should be a social centre,” so he installed both an ice rink and a shooting range at his location. His Canadian counterparts were no less ambitious, staging concerts, lectures and art exhibits on their premises. Simpson’s, founded in 1872 by Scottish immigrant Robert Simpson, once offered an exhibition featuring dead beluga whales carted down from Hudson Bay. (The spectacle is said to have been shut down after three days due to poor ventilation.) By 1930, Eaton’s, Simpson’s and HBC accounted for 14 of every 100 dollars spent in Canada.

That period may well have marked the peak for department stores. Donica Belisle, an associate professor of history at the University of Regina and author of Retail Nation, argues the influence and relevance of department stores came under threat after 1920. New discount retailers set up shop farther from urban centres, which Canadians could reach easily thanks to automobiles. Chains such as Canadian Tire and Zellers spread across the country, while American five-and-dime shops such as Woolworths charged northward. Department stores, with their downtown flagships, were saddled with high overheads and exorbitant rents.

Soon, they began to falter. Simpson’s formed a partnership with Sears, while Morgan’s in Montreal sold to HBC in 1960. The following decade, HBC acquired some of Simpson’s assets and later rebranded the stores. Even Eaton’s lost its way as the retail landscape splintered, squandering the goodwill of older consumers while failing to capture the interest of younger ones. Once one of the world’s largest retailers, Eaton’s filed for bankruptcy in 1999.

That was the same decade in which Wal-Mart expanded to Canada. The retail giant squeezed suppliers to offer rock-bottom prices, an irresistible proposition for a country still recovering from a recession. But the advent of online shopping proved an even more fearsome force than Wal-Mart. Brick-and-mortar chains, including HBC, struggled to adapt. Sears Canada, a confused and neglected brand for the better part of a decade, filed for bankruptcy this year.

READ: Sears Canada: The timeline of its slow-motion collapse

HBC is now controlled by Richard Baker, an American with other storied brands in his portfolio, including Lord & Taylor (est. 1826) and Saks Fifth Avenue (est. 1924). Baker’s background is real estate, not retail, and he’s well aware of the tremendous value locked up in those historic buildings in bustling city centres. In October, HBC struck a deal to sell its flagship Lord & Taylor store in Manhattan for roughly $1 billion to WeWork, a seven-year-old company that provides shared office space for start-ups. Lord & Taylor will operate a slimmed-down store somewhere in the building. The deal is heavily weighted with symbolism: WeWork, a $20-billion new-economy darling, is crowding out a brick-and-mortar relic valued at only $2 billion. WeWork is still selling the dream of personal fulfillment on-site, but the means to achieve it is now labour, not consumption.

MORE ABOUT BUSINESS:

- How Steam Whistle carved a niche for itself in a crowded market

- Top 10 Business Universities

- Angel investing was always male-dominated. That’s finally changing

- Failure is all the rage—for tech companies

- A crash course in Chinese etiquette

- Welcome to Canada, Burger King

- Canadian Tire’s CEO on going high-tech and beating back Target

- Live chat: Tax expert Evelyn Jacks takes your questions