The new kid in town

Pinterest is the fastest-growing social network, and it’s raising serious doubts about Facebook’s lofty ambitions

Macduff Everton/Getty Images; Photo Illustration by Taylor Shute

Share

Like most Canadians, Ellisa Calder is no stranger to social media. The 26-year-old blogs, tweets and keeps in touch with friends and co-workers on Facebook and LinkedIn. But lately she’s been all about Pinterest.

About a year ago, one of Calder’s friends sent her an invitation to the relatively obscure social networking site. It didn’t take her long to get hooked on Pinterest’s remarkably simple concept: surf the Web and “pin” photos onto pages called “pinboards,” which resemble online scrapbooks. The boards can then be organized by themes— “Places I’d like to go,” or “Cool clothes,” for example—and shared with others. Calder, a business analyst for a Vancouver-based IT firm, used the site to plan her upcoming wedding. “A friend and I collaborated on a pinboard where you pin things for inspiration, or things you want to do,” she says. “It informed a lot of the decor.” These days, she’s using Pinterest to assemble ideas on how to renovate her apartment.

But Pinterest is more than a neat tool for planning projects. Calder now checks the site daily—often before she logs into Facebook—to see what has captured the imagination of the people she follows. “You just see beautiful things every day,” she says. “And it’s really easy to consume. You’re just staring at pictures. It’s really addictive.”

Calder isn’t the only one who has caught the Pinterest bug. Though slow to ignite, the two-year-old site has suddenly caught fire. According to U.S. statistics, as many as 12 million people, most of them female, visited the site in January, a tenfold increase from six months earlier. That has some suggesting it may be the fastest-growing social networking site ever. By contrast, Facebook only had about seven million users by 2006, two years after its launch.

While it’s too soon to know whether Pinterest will be a major force to be reckoned with, the site’s sudden popularity isn’t good news for the current social media king: Facebook. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook is in the midst of preparing for a much-anticipated IPO that some expect will value it as high as US$100 billion. Trouble is, those sorts of lofty projections assume Facebook, with 850 million users and counting, will dominate social media just like Google did with search. But as Pinterest’s rapidly growing user base indicates, that may be an increasingly tall order.

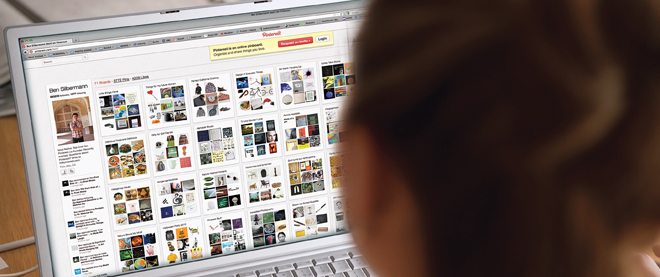

Pinterest is the brainchild of Ben Silbermann, a former Google employee. He started the company in late 2009, hoping to give people a way to share the things they like. After inviting some of his friends to join the following year, he sat back and watched Pinterest slowly increase its reach. “Many of the first people to try the site were from my hometown, Des Moines,” Silbermann told the Chicago Tribune earlier this month (Pinterest didn’t respond to interview requests). That may explain why the service initially took off in the U.S. heartland, where people used it to share recipes and home decorating tips.

Another Pinterest peculiarity is its gender-specific audience. It’s estimated that as many as 97 per cent of U.S. users are female, leading some to dub it “Facebook for women.” That wasn’t necessarily by design (in the U.K., male users are much more common), but the incredibly visual nature of the site makes it a natural fit for showing off fashion, food and beautiful landscapes—not unlike leafing through a giant, glossy women’s magazine. By contrast, Twitter users are more likely to be men while Facebook’s user base is split fairly evenly down the middle.

Now that Pinterest has caught fire, the big question in the fickle world of technology is what happens next. Kaan Yigit, the president of Toronto-based Solutions Research Group, says he believes Pinterest has staying power. “It’s a simple, easy-to-understand metaphor—a bulletin board or fridge—and also to me symbolizes the migration from text-based social media to visual,” he says.

That said, like all Internet phenomena, Pinterest faces the challenge of developing a business model. So far, the site doesn’t make any money. However, it was recently revealed that Pinterest is experimenting with ways to generate revenue through affiliate marketing schemes. For example, if a Pinterest user pins a photo of a coffee maker that links to Amazon, Pinterest could get a cut of the proceeds if the link results in a sale. It’s a potentially lucrative approach—one that’s already being employed by hundreds of thousands of mommy blogs. Recent data suggest Pinterest drove more referral traffic last month than Google+, Reddit, LinkedIn, YouTube and MySpace combined.

Of course, Pinterest needs to be mindful not to turn off users in its quest for dollars—a pitfall that Facebook stumbled into in 2007, when it unveiled its much maligned Beacon program. The service attempted to capitalize on Facebook’s potential for word-of-mouth marketing by tracking users on partner sites, and then broadcasting their activities to their Facebook friends. For example: “Stephen bought a new pair of Nikes on Zappos.com.” Users called it “creepy” and privacy advocates were outraged. Facebook dropped Beacon and Zuckerberg apologized.

With Pinterest, though, there is already evidence it may have an easier time bridging the gap. Whereas Facebook is largely about people and their personal information, Pinterest is mostly about things, including products—whether it’s an expensive pair of shoes or a perfectly prepared meal. In a recent interview with Fastcompany.com, Jeremy Levine of Bessemer Venture Partners, an early Pinterest investor, said he was attracted to the site because he was looking for “a user-generated content media property [based] around products, because products are so wildly monetizable.” Though it’s also true that much of the content on Pinterest is not obviously commercial—pictures of cute animals, for example—Levine noted that the same is true of Google. “Ninety-five percent of the time we use Google, we’re doing things that are completely unmonetizable,” he said. “But in the five per cent of instances, where we’re searching for something commercial, an airline ticket or a Valentine’s Day present, for example, Google monetizes the heck out of those opportunities, and their business model works incredibly well.”

Pinterest’s potential isn’t lost on potential advertisers either. There are already numerous retailers experimenting with the site, ranging from the Gap and Nordstrom to Whole Foods. And although Pinterest is still a pipsqueak compared to Facebook, the fact that Silicon Valley is already buzzing about a new up-and-comer (others on the radar include Chill.com for videos) should give would-be Facebook investors pause. Talk of a US$100-billion valuation for Facebook assumes that Zuckerberg can corral the vast majority of social media ad dollars. But while most people rarely use more than one search engine, they don’t think twice about checking their Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn accounts within the span of a few minutes. “I can see that they overlap in some ways, but each gives you a slightly different mode of self-expression and content discovery and appeals to different senses and audiences,” says Yigit. On the other hand, when it comes to search engines, says Yigit, “Frankly you will settle on the one that gives you the best output.”

That suggests Facebook will be competing with a number of other companies for the same pool of ad dollars. And while Facebook may be the biggest, there is no guarantee it will continue to captivate users—particularly if they find other sites that cater more specifically to their particular interests. “Facebook is becoming the Wal-Mart of social media,” says Yigit. “It wins on size but not necessarily the cool factor.”

An even bigger risk for Facebook is that rival social media sites, even much smaller ones, may prove to be more effective commercially. It’s no secret that Zuckerberg has struggled to turn the Facebook phenomenon into a business. The company’s IPO filings show the company generated US$3.7 billion last year, mostly from advertising, which is still modest compared to the US$9 billion or so Google brings in every three months. Has Pinterest stumbled on a similarly lucrative formula? Calder thinks so. She says she’s already made several online purchases through the site. “I have bought gifts for friends based on things that they’ve pinned,” she says, noting that friends’ pinboards can act like a sort of shopping wish list.

It’s doubtful that Pinterest is keeping Zuckerburg up at night—at least not yet. But potential investors should ask themselves: when was the last time they bought something after logging onto Facebook?