Canada needs a plan to rebuild itself. Let the transformation begin.

Canada is facing a crisis comparable to the Great Depression. Is a total economic rethink our only hope?

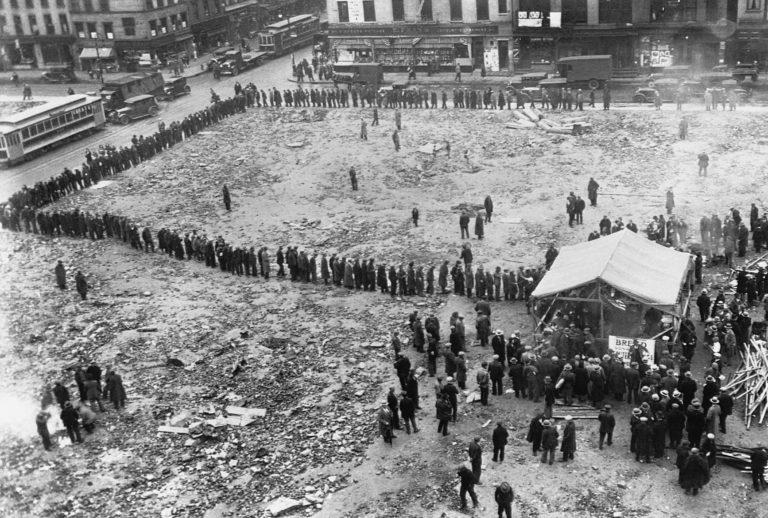

The unemployed and homeless line up for food in New York City during the Great Depression (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Share

On March 4, 1933, Franklin Roosevelt placed his hand on a bible opened to a passage extolling the virtue of charity and was sworn in as president. Around him the Great Depression was at its horrifying worst. America’s banking system was near total collapse, the economy had shrunk by one-third, and one in four workers were jobless, with many more living on sharply reduced wages. Soup kitchens overflowed with the poor and hungry while as many as two million Americans were homeless. As FDR told the crowd that day, fear itself—“nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror”—stood between the desolation of that moment and recovery.

Over the following days and weeks the new administration unleashed a dizzying assault on the economic crisis, providing relief and jobs for farmers, the unemployed and the homeless while launching ambitious projects to overhaul the nation’s infrastructure, including roads, bridges and power dams. The fear soon started to wane, albeit slowly—to this day the record for the biggest one-day gain for the Dow Jones Industrial Index (for those presidents who like to keep score of such things) remains March 15, 1933, when stocks were allowed to start trading for the first time since Roosevelt’s inauguration, though it would take until the 1950s for the market to reclaim its pre-depression peak.

But Roosevelt intended his “New Deal for the American people”—a term he’d first used when he accepted the Democratic nomination the year before—to go far beyond simply reassembling a shattered economy. Three weeks after taking office Roosevelt published Looking Forward, a book drawn from his speeches and articles during the previous year, in which he explained that the New Deal was “plain English for a changed concept of the duty and responsibility of government toward economic life.” It would not be enough just to stanch the downturn with emergency relief, he wrote. “It corrects nothing. From now on we must be far more concerned with the quality of life itself. Concentration upon purely temporary relief measures must not cause a ‘freezing’ of national progress along lines of social equality and justice.” The result would be a sweep of new programs and laws, including social security, minimum wage and unemployment insurance to name just a few, that fundamentally reshaped American society.

READ MORE: The end of economic growth

Almost 90 years later there are some obvious parallels between the challenges Roosevelt faced and those gripping governments today. In the U.S., more than 45 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits since the COVID-19 lockdown began in March. The unemployment rate, at 13.3 per cent in May, is the highest since the Great Depression. Appearing on CNN in April, Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, described the pandemic crisis as “probably the biggest challenge in modern history,” adding that “it may not dwarf but eclipse what FDR faced.”

Canada is enduring an economic crisis on the same grim scale, with more than three million out of work and the unemployment rate at 13.7 per cent. In February, prior to the crisis, more than 83 per cent of prime working-age Canadians were employed. Since then that figure has plunged to 73.7 per cent.

The emergency response from governments and central banks has been historic, in both speed and scale. Since March, governments worldwide have spent more than $10 trillion to stabilize their locked-down economies, while central banks have deployed trillions more to mitigate a wider financial crisis. Here in Canada, Ottawa and the provinces have so far deployed in excess of $300 billion in direct and indirect spending as the economy was put into deep freeze, including payments to workers, wage subsidies for businesses, loans and tax deferrals.

As astonishing as those dollar figures are, they are but the first step in what is certain to be a gruelling and costly rebuild. With provinces slowly lifting emergency restrictions that were put in place to tame the spread of COVID-19, economists, business leaders and lobbyists are eyeing the stimulus measures that will inevitably follow. And as in Roosevelt’s America of the 1930s, many see an opportunity in this crisis to rethink the economy and society.

“We’re going to need bold transformative thinking,” says Kevin Page, the president and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa who previously served as Canada’s first parliamentary budget officer. “Once you get to this side of the mountain on that [pandemic] curve, then you’ve got to launch something that really inspires people and instills confidence, so people can see how you’re going to take the economy out of the freezer and get it going again. We could see an enormous outlay that would really transform the way the economy works and the way people live.”

Until now, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has cautioned that the government’s attention must stay for the time being on addressing the immediate health crisis. “Right now our focus is on getting Canadians through this,” he said during one of his daily briefings in mid-May. But in the same briefing Trudeau indicated his gaze was turning to what comes next. “One of the things we’re very much thinking about is how do we build back better? How do we look at what this pandemic has . . . highlighted around needs or gaps in Canada, and how do we look to rebuild and recover in a way that advances us in the right direction.”

Pressure is already mounting on Trudeau to lay out his plan. Will it focus on short-term so-called “shovel ready” infrastructure projects alongside more conventional measures to juice industries back to life, or will it seek to begin a more fundamental reimagining of the economy? Just as critical will be questions about what political and fiscal limitations the minority Liberal government will face as it tries to implement its stimulus program. The answers to those questions could determine the direction Canada’s economy takes for years, or even decades, to come.

“I look at it this way,” says Kevin Milligan, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia. “Imagine as an extreme example that you’re a war-ravaged economy with your physical infrastructure half destroyed, and you’re starting to rebuild. Do you rebuild the buildings exactly as they were, or do you rebuild in a new design of where you want to go in the future?

“When you’re in the rebuilding phase, this is the opportunity to build toward the goals you want to have for the economy.”

***

The great uncertainty hanging over any discussion about what stimulus might look like—indeed the asterisk to all conversations about the economy right now—comes down to how the pandemic unfolds this year and next. In Roosevelt’s inaugural address he could assure Americans that as severe as their common difficulties were, “they concern, thank God, only material things.” The cost of the present crisis—measured in the deaths of 8,500 Canadians and 470,000 more worldwide—goes far beyond material losses. Without a strong handle on testing and contact tracing, let alone a reliable timeline for a vaccine that can be delivered to the masses, all planning is theoretical. And this doesn’t even account for the possibility of a second-wave outbreak, which could force renewed lockdowns across the country. “We are still very much in the emergency phase of this,” Trudeau said in his press briefing on May 27.

Still, that emergency phase, highlighted by the $40-billion (and counting) Canada Emergency Relief Benefit (CERB) payments to workers impacted by the lockdowns, is winding down, says a federal official who spoke with Maclean’s on background. Assuming that health outcomes—like case counts and hospital capacity—move in the right direction, the restarting phase will see the first round of stimulus targeted at industries decimated by the crisis. (Economists have stressed none of Ottawa’s actions to date should be thought of as stimulus—they are survival measures meant to ensure there would be something left of the economy after the pandemic passes.)

Among the industries clamouring for support: Canada’s major airlines, who have been forced to reduce their schedules by 95 per cent. Before any money flows, however, the government is conducting a deep dive analysis on various sectors to determine what impediments to growth will exist once they reopen. In early May, Industry Minister Navdeep Bains launched a strategy council “to assess the scope and depth of COVID-19’s impact on industries and inform government’s understanding of specific sectoral pressure.”

As this salvage operation gets under way, it would be a mistake to try to preserve all the jobs in the industries hit hardest by the pandemic, says Milligan. Sectors like hospitality and airlines could take several years to recover, he notes, while the energy sector will not realistically see new investment any time soon. “You don’t want to put those parts of the economy on ice and lock people in place until this abates,” he says. “We need to rethink how to reemploy that labour in other sectors.”

That rethink will be part of what is expected to be a much more comprehensive stimulus recovery plan aimed at rebuilding Canada’s post-pandemic economy. When it will come is unknown. Federal officials say it’s premature to discuss details given the government has yet to even formally create a team to begin the process of designing it. (Informal strategizing continues apace—several cabinet ministers recently invited Boston Consulting Group, on an unpaid basis, to advise them on what policies other countries are pursuing with an eye to “charting the course for future-forward recovery,” the Globe and Mail reported.)

Yet Trudeau’s own comments during his briefings, and elements of his government’s emergency response to date, point to a far more activist stimulus response than we’ve seen during any downturn in recent decades. In his daily press briefings he has linked stimulus to vaguely expressed policies like “more equality,” “more digital” and “less pollution, greener outcomes.” When Trudeau announced last month a federal loan program for large companies impacted by COVID-19, he included as a condition that recipients must show they are committed to fighting climate change.

That stipulation rankled many Conservatives and oil patch supporters, who instead called for the Trudeau government to abandon its carbon tax as a way to stimulate the energy sector. “This is the exact wrong time to relax carbon pricing,” says Milligan. “When you’re in a rebuilding phase, you want to make sure that the sectors that are pushed to grow coming out of this get us to the goals we want as a society. Canada has set out a goal for 2050 of carbon neutrality. We should keep that goal in mind.”

RELATED: What Canada’s COVID-19 economic stimulus plan should look like when it comes

Clean energy companies and lobbyists are already positioning themselves to be part of the green stimulus windfall. Several groups have formed to push for a massive investment in cleantech as part of the Trudeau government’s plan.

The Trudeau government would not necessarily be alone on the world stage if it were to pursue a green stimulus program—in late May, the European Commission proposed a $1.5-trillion stimulus package, including funding for renewables, electric cars and hydrogen technology that the Bloomberg news agency characterized as “the world’s most climate-ambitious stimulus package.” Likewise the government of South Korea unveiled an $85-billion “Korean-version New Deal” on June 1 with support for green technologies as well as investment to promote the use of artificial intelligence and fifth generation (5G) wireless networks across the economy.

Others see a post-pandemic opening for sweeping reform of social programs that leads to a national guaranteed minimum-income program. “What the pandemic has done is made us all recognize how precarious the veneer of our lives is,” says Evelyn Forget, a professor of economics at the University of Manitoba and long-time researcher of the basic income concept, which she describes as insurance against job insecurity.

The inadequacy of Canada’s current employment insurance program, which ignores freelance and gig workers, became apparent in the early days of the lockdown when Ottawa had to replace it with CERB and its monthly $2,000 payment to people who lost income due to COVID-19. The opportunity now exists, Forget says, to evolve CERB into a targeted minimum-income program once the pandemic has passed.“There is a will right now,” she says. “I don’t think Canadians are going to be willing to let low-income working people bear the consequences of this pandemic.”

At some point soon, planning must turn to action, says Page, starting with a fiscal update. “[Trudeau] has been ambivalent about that, saying there is too much uncertainty,” he says. “But think of the uncertainty FDR faced and that didn’t stop him.” (Update: On June 17, after the print version of this story was published, Trudeau set a date for his government to release a fiscal “snapshot” of federal finances—July 8.)

***

As the Trudeau government’s stimulus plan does take shape, one topic is certain to feature more prominently than all others in the debate. As incoming Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem told Reuters in early April: “I expect there will be economic damage and there will be a need for some more traditional types of stimulus. The top of that list would be infrastructure spending.”

Shortly after, Infrastructure Minister Catherine McKenna told the Globe she’d been “reading up” on Roosevelt’s New Deal while hunting for “shovel ready” projects the government could quickly ramp up to stimulate growth.

Building bridges, roads and tunnels is, admittedly, the first thing that comes to mind for most people when they hear the word stimulus. Many will recall the green and blue “Action Plan” signs that blanketed the country after 2009 as the Stephen Harper government rolled out its effort to combat the Great Recession. (Make no mistake—if someone in the Trudeau government isn’t already devising a slogan and brand design for its stimulus scheme, they soon will be.) But “infrastructure” is also a term whose definition politicians have increasingly stretched over the years far beyond the realm of dusty hard hats, and that’s enabled them to fill that spending bucket with whatever projects suit their goals. The Trudeau government’s 12-year, $188-billion Investing in Canada Plan, launched in 2016, has social, cultural, green and recreational infrastructure components that critics have long complained dwarfed projects that improved Canada’s crumbling trade and transportation systems. Another persistent problem McKenna must fix: the plodding pace with which the Liberals have been able to get the money out the door.

Regardless of what form new infrastructure takes, it’s an approach welcomed by municipalities that have seen their finances collapse amid the pandemic. Calgary, for instance, faces a $235-million budget shortfall, while Toronto’s budget gap stands at $1.5 billion. “Investing directly in Canada’s communities and local infrastructure projects will help get this country back on its feet after COVID-19,” says Bill Karsten, president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities lobby group, who adds the federation is in talks with the government about infrastructure programs. “But the fact is there will be no recovery unless municipalities first get the support they need to get out of this financial crisis.” Some relief came early in June when Ottawa said it would advance $2.2 billion in gas tax funding to municipalities.

Not everyone is enthused by talk of infrastructure stimulus, to say the least. “A public works program is obviously just dumb,” says Stephen Gordon, an economics professor at Université Laval, who notes there is little excess capacity in the construction industry so it would not absorb many job seekers.

But Gordon points to two more fundamental problems that raise questions about the effectiveness of infrastructure right now. One is that this crisis differs from conventional downturns, including the Great Depression, which were driven by a collapse in demand that could be reignited through government intervention, like the New Deal. The present crisis instead entails both a crippling of global supply chains and a hit to demand since consumers are either prevented from going out to spend or feel nervous doing so until there’s a vaccine. “The usual tools of a standard recession, paying people to dig ditches and then fill them back in again, that’s not going to solve the problem here,” he says.

READ MORE: Coronavirus won’t hit Alberta as hard as others. But its economic wallop will be brutal.

The other flaw is that the recession has hit the service sector and women particularly hard, and women shoulder considerably more of the burden of childcare in households. As such, he calls the traditional recession-fighting recipe of infrastructure a “cruel joke.”

Milligan has heard these complaints from his economist colleagues before, but still sees infrastructure as crucial to fighting this crisis, even if it requires a different approach than in the past. For instance, a social infrastructure program could expand and overhaul daycares so that parents can return to work more easily. The point is, the pandemic will leave a deep and lasting mark on parts of the economy that will require every tool at our disposal. “We’re still in a world with very low interest rates,” he says. “The case for infrastructure is still there.”

***

Last month, Stephen Harper took to the op-ed pages of the Wall Street Journal to dismiss suggestions that the pandemic has ushered in an era necessitating “big, and wise government,” words he attributed to an unnamed “leftist” writer. The opposite will be true, Harper insisted, because the outcome of all this spending today will be sovereign debt crises and austerity tomorrow unless free enterprise and fiscal responsibility are embraced.

That writer, as it turns out, was Margaret O’Mara, a professor of history at the University of Washington who studies Silicon Valley. Apart from her surprise at being labelled a “leftist” by a former world leader, she sees parallels between those pushing back against government efforts to revive the economy and the response in the early 1930s to the Great Depression. “[Then-president] Herbert Hoover believed government’s role was to create an environment where business was free to do what it could do, and that government was an impediment to economic growth,” she says. “It echoes through the ages”

In the end, as unemployment soared and the end of Hoover’s first term neared, he switched gears and launched a battery of policies to fight the worsening crisis, including a massive public works program. (A member of Roosevelt’s own “brain trust” would later admit that “practically the whole New Deal was extrapolated from programs that Hoover started.”) It was the start of an “epochal shift,” says O’Mara, from the laissez-faire 1920s to an era of expanding government involvement in the economy that continued right up until the 1980s, when the mantra of tax cuts and red tape reduction took over. Now, in her estimation, the U.S. could be on the cusp of another abrupt shift if Biden and the Democrats take power in November. “Crisis is an accelerant to change,” she says.

But Harper’s op-ed was also a reminder that the fiscal and political pressures that largely receded during the first months of the pandemic emergency are re-emerging.

RELATED: How Denmark got ahead of the COVID-19 economic crisis

Questions about Canada’s ability to pay its stimulus tab are simpler to address. The federal government entered the crisis in relatively healthy fiscal shape compared to other developed nations, despite Trudeau’s repeated failure to live up to his deficit-reduction promises. “There is a path out of this that will get us to fiscal sustainability, so I don’t think we’re headed for a sovereign debt crisis in Canada if we are able to do some recovery over the summer,” he says, noting that even if Canada borrowed $500 billion, the cost to service that debt at such low interest rates is equal to half a point of the goods and services tax (GST). In a recent report, the Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux estimates the federal debt will grow by $255 billion over the 2019/20 and 2020/21 fiscal years to $962.1 billion—though he’s also said it’s “not unthinkable” Canada’s total debt load could reach $1 trillion this year.

However all bets are off if jobs don’t begin to recover this summer, or a second-wave pandemic hits, says Milligan. “If we have an L-shaped recovery with 7.5 million people still out of work, that’s going to be an economic and fiscal calamity.”

How quickly the economy recovers will also determine how much political bandwidth the Trudeau government has to borrow and spend. At the moment the Liberals are riding high in the polls and there’s ready acceptance of government efforts to fight the downturn. “The public appetite for stimulus is not unbounded but it’s certainly of a magnitude we haven’t seen in many years,” says Frank Graves, president of Ekos Research. “It’s not like the public is giving the government complete carte blanche, but close to it.”

Still, Trudeau is stuck with a minority government until the next election, a far cry from the remarkable control Roosevelt wielded in 1933, thanks to his landslide election victory and an agreeable Congress. The Liberals’ aborted attempt to give themselves power to tax and spend without oversight until 2022, as they proposed in a draft of their emergency pandemic legislation in March, or even their agreement with the NDP to put Parliament on ice until September, won’t change that.

It makes a New Deal on the scale of what Roosevelt accomplished in his first 100 days in office—14 pieces of major legislation passed, with one bill sent to the president and signed just seven hours after he’d submitted it to Congress—a non-starter.

That doesn’t mean Roosevelt can’t offer Trudeau a lesson if he wants one. In his book Looking Forward, Roosevelt argued Americans caught in the economic crisis wanted “bold persistent experimentation” to get them out of it. Sounding almost like a modern technology CEO, he wrote of his New Deal strategy, “It is common sense to take a method and try it; if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

Editor’s note:

We hope you enjoyed reading this article, and that it added to your understanding of the ordinary and extraordinary ways Canadians are staring down this pandemic.

But quality journalism is not free. It’s built on the hard work and dedication of professional reporters, editors and production staff. We understand this crisis is likely taking a financial toll on you and your family, so we do not make this ask lightly. If you are able to afford it, a Maclean’s print subscription costs $24.95 a year—and in supporting us, you will help fund quality Canadian journalism in this historic moment.

Our magazine has endured for 115 years by investing in important stories and great writing. If you can, please make a contribution to our continued future and subscribe here.

Thank you.

Alison Uncles

Editor-in-Chief, Maclean’s