Both the NDP and UCP support a price on carbon. It’s time we admit it.

It may sound odd, especially in today’s highly polarized Alberta, but Jason Kenney and Rachel Notley have more in common when it comes to carbon pricing than most realize

United Conservative Party leader Jason Kenney speaks in Edmonton Alta, on Monday January 29, 2018. Edmonton’s pride festival has rejected an application by the opposition United Conservative Party to participate in its parade.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

Share

Trevor Tombe is an associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary, and a research fellow at the School of Public Policy

“Jason Kenney says he supports a carbon tax” — a headline many Albertans probably didn’t see coming. But, it’s true.

“Scrap the Carbon Tax” really means “Scrap a Carbon Tax.”

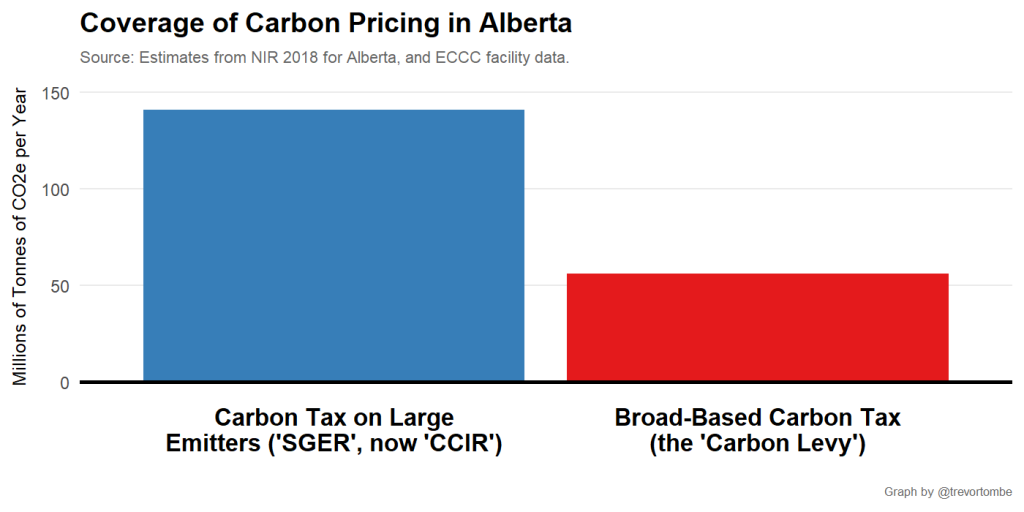

Alberta has two carbon pricing systems. And despite the heated rhetoric directed at one, there is broad agreement behind the other (larger) one.

Though it may sound odd, especially in today’s highly polarized Alberta, the NDP and UCP don’t disagree on everything when it comes to climate policy. Both support taking action to lower GHGs. Both support carbon pricing of one type or another. Both support using the revenue in a way that is not, strictly speaking, revenue neutral. And both support additional rules, regulations, and subsidies.

I’ll explain.

Alberta’s carbon tax, old and new

Over ten years ago, Alberta became the first jurisdiction in North America to put a price on carbon. Under Conservative Premier Ed Stelmach, the province created what was called the Specified Gas Emitters Regulation. Don’t let the anodyne name fool you. This was a carbon tax.

Any facility emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of GHGs, such as many oil and gas facilities or power generators, would be assigned a certain amount of allowable emissions. Any emissions above that level would potentially face a $15 per tonne charge. (I say ‘potentially’ since there were other compliance options, but those do not concern us here.)

Fast forward eight years, and the new NDP government made two big changes to carbon pricing in Alberta. (I’m over-simplifying, but it’s okay.) First, they changed the structure of the old system and renamed it the Carbon Competitiveness Incentive Regulation. Second, they broadened the coverage using a second carbon tax on fuel use.

The second tax is the controversial one, but it is the smaller of the two.

Kenney proposes to return Alberta to just the large-emitter system. This is what the CBC headline was all about. In short, Mr. Kenney proposes a carbon pricing regime with roughly two-thirds the coverage of the current government’s approach. He proposes to cancel the red bar, not the blue.

There are implications of this choice. Without pricing on smaller emitters (i.e., you and me), there will be less emissions reductions than otherwise. To achieve the same emissions reductions as current policy, the opposition would have to adopt a higher price on large-emitters or more stringent rules and regulations. This would come at greater costs. And by cancelling carbon rebate program, lower income households in Alberta will be made financially worse off.

But debating these points is already an improvement to the black-and-white “job-killing carbon taxes” rhetoric we tend to hear. The opposition in Alberta doesn’t reject carbon pricing in principle, they just prefer a different design with narrower coverage.

How to use the money from carbon pricing

Alberta’s large emitter carbon tax isn’t revenue neutral. It never was. And neither the government nor Kenney propose to change that.

Instead of lowering other taxes with the proceeds, both prefer to subsidize green technology developments (and other such initiatives) and provide support to trade exposed sectors. The latter makes a great deal of sense.

Carbon pricing raises costs. For some trade exposed sectors, like oil and gas, this is a problem. To address these competitiveness concerns, facilities are given free emissions credits—a subsidy in all but name. (For more, see this.)

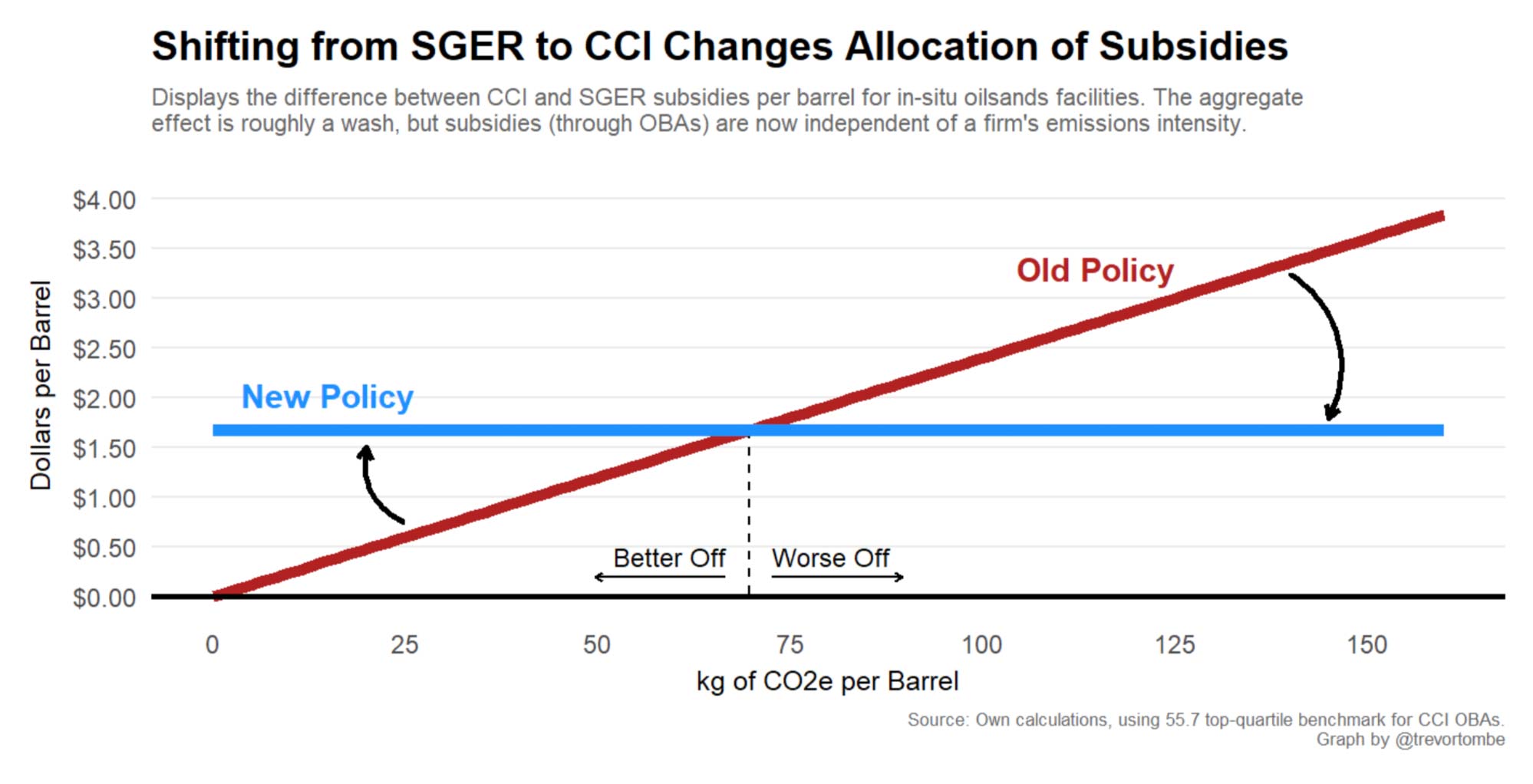

Where the government and opposition may differ is in how this support is allocated across firms. The old system allocated emissions credits to effectively give a larger subsidy to more emissions intensive facilities. The new system is far more uniform. Here is an illustration for in-situ oil sands:

If you lowered your emissions, you’d receive a lower subsidy. This clawback undercut the incentive to lower emissions. If a firm installed better equipment to lower emissions, they would only save $0.30 per tonne, not the full $15/t. Under the new system, which gives the same subsidy to all within the sector, the full incentive to cut emissions remains.

Does Kenney propose to reverse what Notley did to Alberta’s large emitter system? That is unclear.

Revenue neutral carbon tax?

If a plain-vanilla carbon tax of $30/t were levied on large emitters, it would raise roughly $4 billion per year. But support to industry eats up all but roughly a half billion dollars today. And both government and opposition agree on what to do with it: subsidize technology.

Emissions Reduction Alberta was started nearly ten years ago to handle proceeds from SGER. It funds a wide variety of projects. One of its largest recent projects will involve $25 million provided to a solvent-extraction demonstration project to extract bitumen without steam. Another funds a project by MEG to try and convert bitumen into a form that can flow through a pipeline without first being diluted. The list is a long one, including a recent announcement of a new Energy Innovation Fund to provide $1.4 billion over the next seven years slated for oil sands innovation, industrial energy efficiency, bioenergy, and so on.

Instead of spending the half billion to subsidize technology, one could make the carbon tax on large emitters revenue neutral by lowering other taxes elsewhere instead.

There are alternatives: cut the first-bracket personal income tax rate from 10 per cent to 9.6 per cent, cut the corporate tax rate back from 12 per cent to 10 per cent, eliminate taxes completely on small businesses (and still have money left over), and so on.

Funding technology has its pros and cons, to be sure, but both major parties in Alberta prefer to spend the large emitter carbon tax revenue rather than lower other taxes. Neither wants a revenue neutral large emitter carbon tax.

More agreement than most realize

Climate policy, broadly speaking, involves one of three types of instruments:

- Carbon pricing (carbon taxes, cap-and-trade, levies on large emitters, etc.)

- Rules and regulations (equipment mandates, intensity standards, building codes, etc.)

- Subsidies (for technology adoption or development, energy efficiency programs, biofuels, carbon capture, etc.)

Today, every major party in Alberta opts for an all-of-the-above approach. They all support policy that includes ingredients from each of the above three bins.

There can and should be vigorous debate over the mix and over the details, but there is already more agreement than most care to recognize. The rhetoric surrounding carbon pricing is intense and often misleading. We can do better, especially in debates over a price on carbon in Alberta.

All major parties support carbon pricing in some form or another. It’s time we admit it.