Canadian exporters are finally waking up to opportunity in Asia

Canadians are struggling to make the most of trade opportunities shifting across the Pacific

SHENYANG, July 7, 2015– An investor looks through stock information at a trading hall in a securities firm in Shenyang, northeast China’s Liaoning Province, July 7, 2015. Chinese shares lost to negative territory on Tuesday, with the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index down 1.29 percent to finish at 3,727.13 points. The Shenzhen Component Index slumped 5.8 percent to close at 11,375.6 points. Xinhua News Agency/Getty Images

Share

This story by Kevin Carmichael was originally published by Canadian Business.

Canada’s exporters may be figuring it out: the future is in Asia.

Policy makers have been trying to nudge Canadian executives to the Pacific for years. Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada governor, used a speech in 2012 to counter the excuse that Canadian companies were uncompetitive; Carney presented evidence that showed exporters struggled after the crisis because they were overexposed to slow-growth markets such as the United States and Europe. (More than a dozen Asian countries grew at least 5% that year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The U.S. economy expanded 2.2% and that of Europe effectively stalled.) Former prime minister Stephen Harper signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade agreement that would bind 12 Pacific Rim nations. The new government of Justin Trudeau hasn’t yet said whether it will stay in the TPP, but it would be a shock if it reneged. Asia is on the mind of Canada’s leader. The only two nations mentioned by name in Trudeau’s mandate letter to Trade Minister Chrystia Freeland are China and India. He referred to them twice. (Neither China nor India are members of the TPP.)

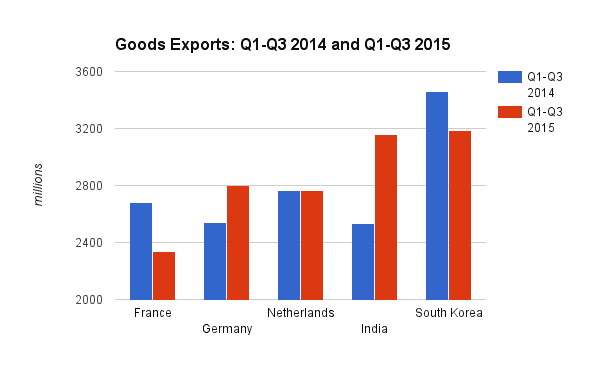

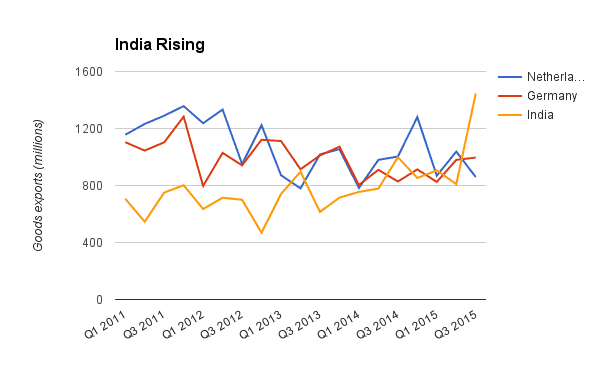

A pivot to Asia may already be on. Merchandise exports to China continue to grow, and the world’s No. 2 economy now is firmly Canada’s second-largest trading partner after the United States. Shipments of goods to India surged to a record in the third quarter, according to data released by Statistics Canada last week. Asia’s third-biggest economy is on track to leap over France, Germany and the Netherlands to become Canada’s seventh-biggest market for merchandise exports. South Korea, with which Canada signed a free-trade agreement that went into effect in January, is on its way to securing its place as a more important economic partner than any of the big countries of continental Europe.

The U.S. still matters most to Canadian traders: Americans purchased 76% of the $134 billion worth of goods that Canadian companies sent abroad in the third quarter. The United Kingdom is the third-biggest destination of Canadian merchandise exports after China. Japan is No. 4 and Mexico is No. 5. The reshuffling occurs in the bottom half of the Top 10. When the books close on 2015, India and South Korea likely will have supplanted continental Europe on Canada’s export league table. Canada shipped goods worth $1.45 billion to India in the third quarter, a 78% increase from the previous quarter and almost double the year-earlier amount, as back-to-back droughts increased demand—and prices—for lentils and other pulses. Through the end of the third quarter, Canadian goods exports to India were valued at $3.16 billion, slightly less than the $3.19 billion of stuff sent to South Korea.

Is the shift permanent? Probably, if only due to gravitational pull of growing demand. But there still is reason to the ability of Canadian companies to take full advantage. As I’ve argued previously, Corporate Canada is notoriously timid. Glen Hodgson, a former Finance Canada official who now is chief economist at the Conference Board of Canada, calls Canada’s trade performance over the last decade “mediocre.” That’s problematic because the trade winds have changed since Carney’s speech more than three years ago. Hodgson calls it the “next trade era.”

The real money over the longer term still will be made in places where English isn’t the first language. But the emerging-market superstars of a few years ago—Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa; the BRICS—no longer are growing in a straight line north. China is slowing as Beijing attempts to orchestrate a soft landing from years of unsustainably fast economic growth. Brazil and Russia are in recession; South Africa’s GDP will expand a mere 1.3% in 2016, according to the IMF. These three countries were hit hard by the collapse of commodity prices. India alone retains some shine. It now is the world’s fastest-growing major economy, advancing at an annual rate of about 7.5%.

The collapse of oil prices and other commodities hasn’t helped Canada, either. It has wiped out wealth that could otherwise be used to finance expansion and technological upgrades. The Canadian dollar has weakened to about 75 cents against the U.S. currency, making Canadian goods and services relatively cheaper on the world market, but boosting the cost of investing abroad. The U.S. economy won’t startle anyone with its vigour, but it does seem to found decent momentum. That’s good for Canada, at least in the short-term.

This is a tricky environment. Hodgson and the Conference Board are in the midst of an assessment of whether Canadian companies are up to the challenge. “Our preliminary assessment is they are not,” Hodgson said in a commentary earlier this month. He laments the dismal amount of money Canadian executives spent on their companies in recent years. Now they either are struggling to keep up with orders or unable to approach new markets. “It is primarily the responsibility of businesses, not policy makers, to up their game through investment,” Hodgson said.