Apps for children: It’s a booming market

Work-and-play mode is particularly congenial to the little ones

Share

Away from the hype that surrounds some of the hottest Internet companies in Silicon Valley, scores of developers are tackling the lucrative, accelerating sector of technology for children. “Backpacks will slowly shrink… Textbooks will pretty soon be delivered on tablets,” says Warren Buckleitner, editor of Children’s Technology Review, a publication that since 1993 has been tracking new releases and trends in this increasingly busy domain. “It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.”

The boom in technology designed around children’s needs was catalyzed by the launch of Apple’s iPad in 2010, says Buckleitner, a former teacher with a Ph.D. in educational psychology. The tablet, he says, was the first reasonably priced device to bring together the must-have features of a blockbuster piece of hardware for kids: wireless Internet connection, powerful batteries, an App Store that has galvanized independent developers as well as those working within companies, and a large multi-touch screen.

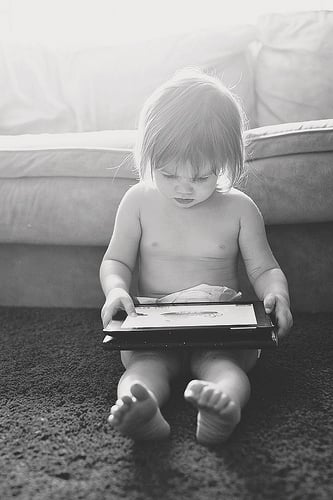

“We knew that magic happens when you put touchscreens in the hands of children,” says Emil Ovemar, producer and co-founder of Toca Boca (which means ‘touch mouth’ in Spanish), a maker of games for Apple devices within Bonnier, a large Swedish media conglomerate with yearly revenues of almost US$4 billion. The work-and-play philosophy behind Apple devices seems to fit particularly well with the way children operate. “The most natural way to learn something is through play,” notes Ovemar.

Most parents seem to agree. Kids Industries–a marketing agency that targets the family marketplace–found that 77 per cent of 2,200 parents it surveyed in the U.S. and U.K. believe that interacting with a tablet helps their children develop creative thinking and gain problem-solving skills.

The magic, in fact, was already at play–even before the iPad–in touch-screen phones. Another recent study by Kids Industries found that while only nine per cent of pre-school children in different countries can tie their shoes, about 20 per cent can play an app on a smartphone.

No wonder app developers are starting to focus on children. Ovemar and colleagues create games revolving around everyday activities like cutting hair, cooking or serving tea. In their most recent game, named Toca Kitchen, the user can drag a variety of foods from the fridge to the kitchen, cook them and swipe them into the mouth of one of four characters. Toca Boca launched the first of the 10 games now for sale in Apple’s App Store in March 2011. Since then, the apps have been downloaded 4.8 million times–although often for free. They are most popular in Sweden and in anglophone countries (Canada is the company’s fifth biggest market,) but fare well also in the Middle East too.

The children’s app market is so young, few have set out to measure how big it may be, the Financial Times notes. But the study on moms and dads in the U.S. and U.K. by Kids Industries found that parents download around 27 apps a year on average for their children. Pare that with estimates that sales of tablets will skyrocket to over 63 million this year, and it’s easy to see the potential.

Admittedly, the growing jungle of apps poses challenges for parents struggling to discover the best products and keep up with the pace of innovation. But Ovemar predicts it’s schools that will struggle the most along the app-laden learning curve. “I don’t think schools are ready to handle the generation that grows up with touchscreens. There will be a huge mismatch,” he says.

Buckleitner, though, is convinced that pedagogues from past centuries, like Maria Montessori or Friedrich Fröbel (the inventor of the kindergarten), would have embraced the new wealth of hardware and software for children with enthusiasm. “I think Montessori would say to not give a child an iPad is a form of neglect,” he says. “Who doesn’t want a child to learn to read? Well guess what, there’s 50 apps right now that make words into toys, where a child’s finger can drive language.”