Oil exports drive Canada’s trade surplus with the U.S.

Econ-o-metric: Canadian arguments about balanced trade with the U.S. don’t matter to Trump. His NAFTA logic says deficits are for losers, full stop.

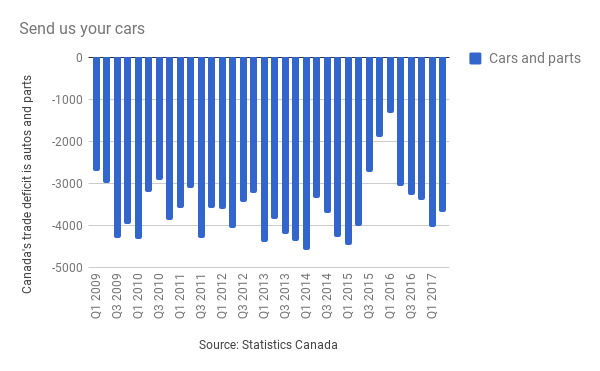

Canada’s auto industry is exporting fewer vehicles than the country imports.

Share

Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland says Canada doesn’t measure the value of trade in terms of deficits and surpluses. But U.S. President Donald Trump does, which is why Statistics Canada’s latest trade data will be more political than usual.

In the second quarter, Canada shipped goods to the United States worth $10.4 billion more than the stuff imported from its largest trading partner.

READ MORE: A NAFTA ‘tweak’? Dream on.

That’s a smaller surplus than the previous quarter, but still one of the wider gaps in recent years. One of the Trump administration’s main goals in triggering a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement was narrowing the U.S. trade deficits with Canada and Mexico. Washington will have taken note.

Why it matters

Freeland is right: surpluses and deficits are an overly simplistic way to measure the benefits of trade. A deficit can signal economic health because it suggests consumers are benefiting from cheaper goods and companies are investing in stuff they can’t purchase at home. But Trump and his chief trade negotiator, Robert Lighthizer, don’t see it that way. They treat trade data like the box score of a sports match. For them, a deficit means you are losing—and Trump doesn’t like to lose.

The trend

Canada’s trade surplus with the U.S. stands out because it runs a deficit with the rest of the world. Meanwhile, the shortfall in the current account, which tracks the flow of goods, services, and investment, widened to $16.3 billion in the second quarter from $12.9 billion over the first three months of the year and $11.7 billion in the fourth quarter. The previous two quarters now appear to be anomalies. For most of 2015 and 2016, the quarterly current-account deficit was $16.3 billion and $18.8 billion.

The surplus in goods trade with the U.S. was the smallest since the third quarter of 2016, as weaker prices decreased the value of oil exports. The average quarterly surplus in 2015 and 2016 was about $8.3 billion.

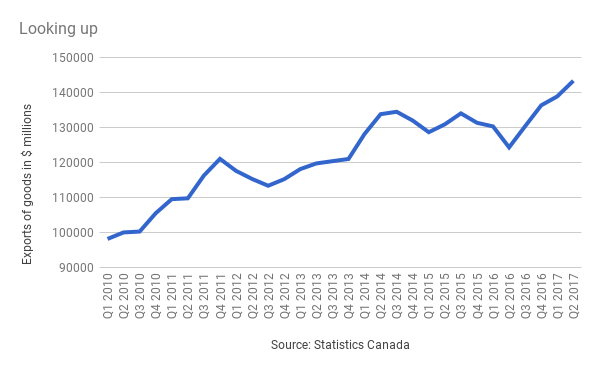

It is also worth noting that despite the overall deficit, receipts from the export of goods climbed to the highest according to records that date to 1981.

Glass half full

At the negotiating table, Canada will argue that its trade surplus with the U.S. is exaggerated by energy. StatsCan’s newest data don’t break down which goods were shipped to whichever country. But they do detail the types of goods that were exported and imported in aggregate, and we know that most of Canada’s energy exports go south of the border. Canada’s surplus in energy was $16.2 billion in the second quarter, even as it ran a goods-trade deficit of $5.2 billion. That means Canada’s trade advantage with the U.S. is flattered by shipments of oil and electricity,

To distract from the Trump’s administration’s obsession with headline trade figures, Canada might highlight trade in automobiles. Trump talks often about bringing car-and-truck production back to America. It will be difficult to argue that Canada is stealing those jobs. Canadian exports of motor vehicles and parts increased in the second quarter, but we still ran a sizeable deficit:

Glass half empty

There is more to trade than stuff.

International direct investment in Canada fell off a cliff in the second quarter, as non-Canadians fled the oil patch. Overall, foreign investment in Canada was a meagre $223 million in the second quarter, the lowest since 2010, according to StatsCan. Inward investment from merger and acquisitions plunged by $8.1 billion, the first decline since the first quarter of 2015.

Bottom line

In purely economic terms, the trade data are an overall positive for Canada. Stronger exports have been a long time coming, and should encourage those benefiting from healthier global demand to invest. The sharp drop in direct investment is a concern, although the decline is magnified by the decisions of a few big international oil companies to leave northern Alberta. But even a smaller trade surplus in goods with the U.S. will continue to attract the Trump administration’s attention. At the start of the NAFTA negotiations, Freeland emphasized that without energy, Canada’s trade with the U.S. has been balanced in recent years. Lighthizer was having none of it. He countered with a cumulative figure from the past decade that implies “balance” is a recent phenomenon. Recent history means little to the Trump administration. Its grievances are measured in the 23 years since NAFTA went into effect.