The real costs and benefits of carbon pricing

Opinion: Yes, carbon pricing, like all climate policies, will have economic costs. But that doesn’t mean we should take no policy action.

(Lucas Oleniuk/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Share

Dale Beugin is the Executive Director of Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission. Chris Ragan is Chair of the Ecofiscal Commission, the Director of the Max Bell School of Public Policy and an Associate Professor of Economics at McGill University.

Last week saw lots of talk around the economic costs of carbon pricing. In one sense, that’s appropriate. In fact, policy costs are exactly why economists like carbon pricing—because it can reduce greenhouse gas emissions at a lower economic cost than any other policy approach. But the concept of cost is not always clear, and the conversation last week was sometimes inaccurate and incomplete.

Let’s take a close look at the real costs of carbon pricing, while also considering the real benefits—something that last week’s conversations mostly ignored—as well as the costs of alternative approaches to reducing GHG emissions.

Well-designed carbon pricing will have a small economic impact

Start with the bottom line: the costs of carbon pricing are real, but small. The most comprehensive measure of the country’s national income is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Reducing GHG emissions using any type of policy will almost certainly involve a cost in terms of lower GDP, especially over the short term. After all, if reducing GHGs was free, we wouldn’t need intentional policy actions.

But the size of this cost depends on the specifics of the policy used. The analysis by the Ecofiscal Commission suggests not only that carbon pricing involves lower costs than other policy approaches, but that the GDP cost is low in absolute terms.

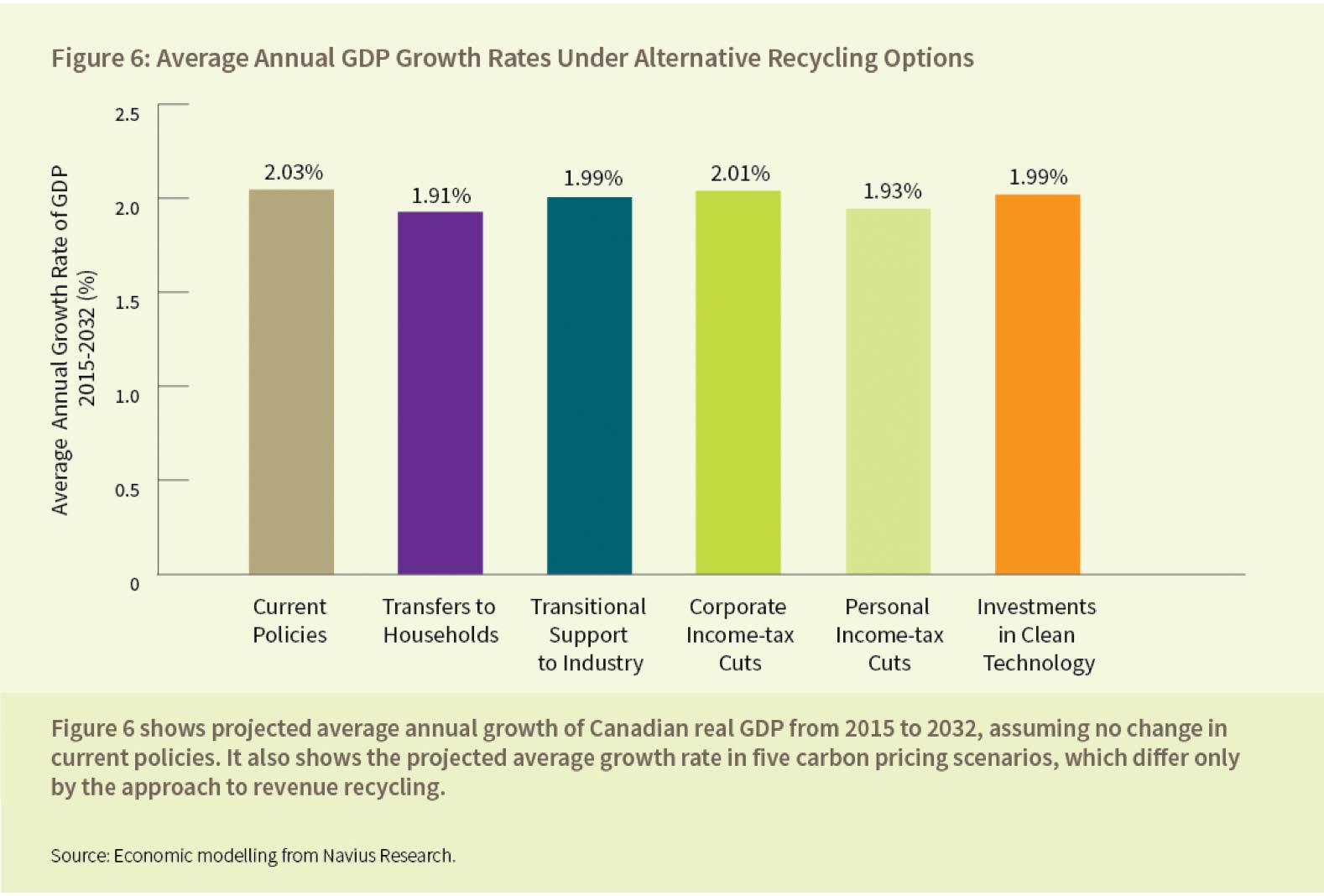

READ: Saskatchewan is launching a court reference that just might kill the carbon tax

The figure below shows the projected average annual growth rate of GDP from 2015 to 2032 under various carbon-pricing scenarios, including one scenario without new policy (the one on the left). The five scenarios on the right all have the same carbon price, starting at $30 per tonne and steadily rising to $100 per tonne by 2027, but they differ by how the carbon-pricing revenues are “recycled” back into the economy. There are small differences between these scenarios, but in each case we see that the annual rate of GDP growth is only slightly lower than it would be in the absence of the carbon price.

But look again at those numbers, closely. Under all carbon-pricing scenarios, economic growth is pretty healthy. Carbon pricing isn’t a massive blow to the economy. The differences in the projected annual growth rates are typically less than one-tenth of a percentage point, within the margin of error of the modelling tools we use for these projections.

Three odd aspects of the recent PBO report

The projected impact of carbon pricing on GDP brings us to last week’s report from the Parliamentary Budget Office. The PBO’s numbers are broadly based on Ecofiscal’s estimates as shown in the figure above. But the PBO frames their analysis a bit weirdly, in a few ways.

First, the PBO used our modelling results to estimate the impact of the carbon pricing scheduled to occur under the Pan-Canadian Framework (PCF). But our modelling assumed a higher carbon price, and broader coverage of GHG emissions than what we are likely to see with the PCF. Ecofiscal’s analysis is based on a nation-wide carbon price that starts at $30 (per tonne) in 2015, rises to $50 in 2021, and then hits $100 by 2027. In contrast, carbon pricing under the PCF will be a bit uneven across provinces, but the minimum “federal backstop” will be $10 this year, $20 by 2019, and $50 by 2022.

As a result, Ecofiscal’s assumed carbon pricing policy is not the same as under the PCF. Based on further communications with the PBO, it appears that the PBO attempted to adjust Ecofiscal’s results to compensate for these differences. Yet the models used for these analyses are complex. Somewhat arbitrary adjustments to results mean that the PBO report does not really assess what it claims to be assessing.

READ: Alberta’s strong carbon policy is key to getting pipelines built

The second odd thing is that the media discussion surrounding the PBO report didn’t pay enough attention to revenue recycling. The PBO report highlighted the economic costs associated with the form of revenue recycling that is the worst case for its impact on economic growth. Governments could choose to send rebate cheques to households, and this would naturally be popular with many people, but it would miss an opportunity to use the carbon-pricing revenue to reduce growth-retarding income taxes.

As the PBO notes (though media coverage did not), alternative approaches to revenue recycling would significantly lower costs. If the government chooses instead to (for example) use the revenue to reduce either personal or corporate income taxes, the overall impact on GDP growth would fall to almost zero, as shown in the figure above and in our report on revenue recycling. Further, the PBO analysis neglects the fact that carbon pricing policies in Alberta, Ontario, Quebec as well as the federal backstop provide transitional support to industry in the form of “output-based allocations.”

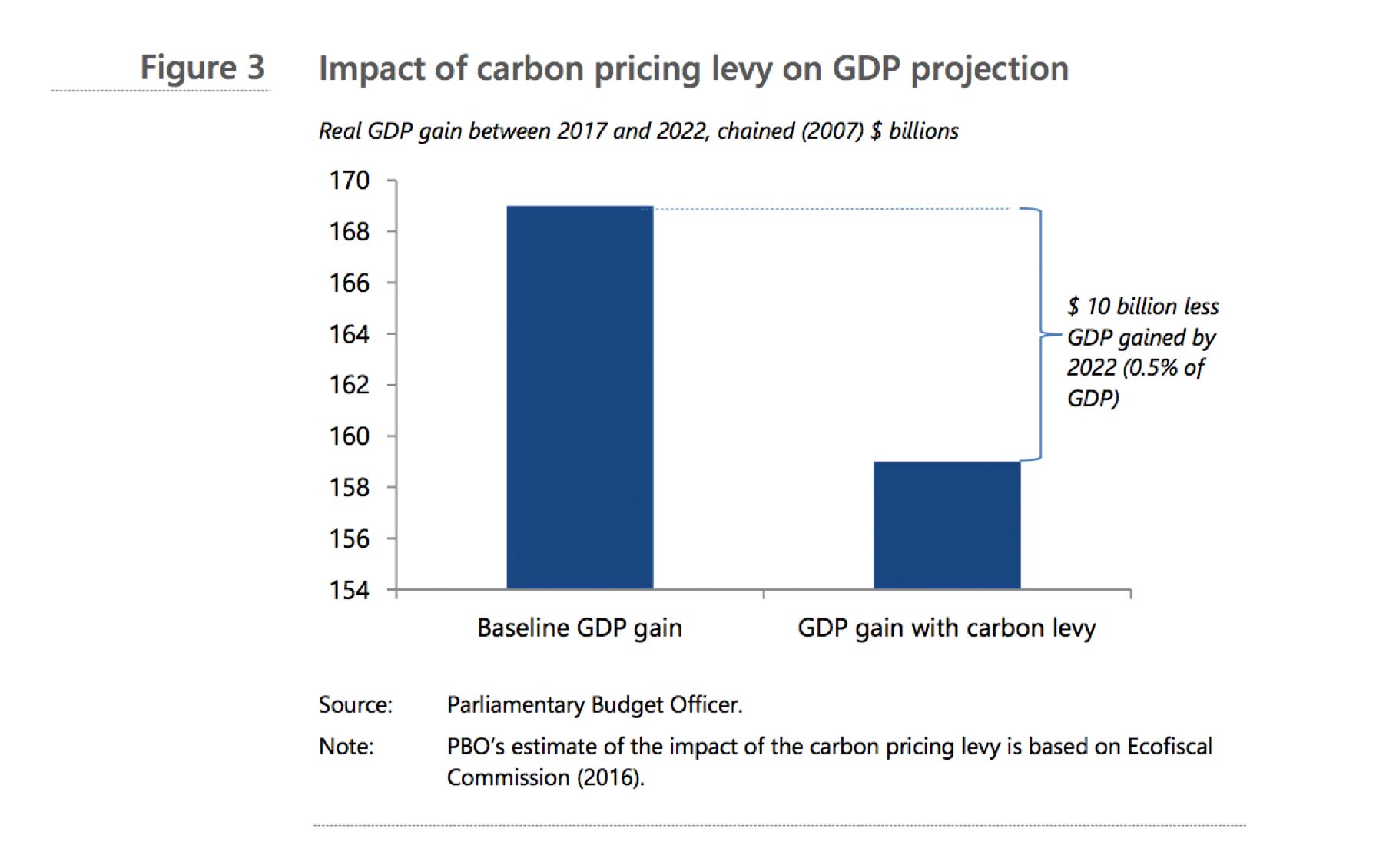

The third odd thing— and this is a bit of a data-nerd quibble, we admit—is the way this growth impact is illustrated in the PBO report. PBO’s Figure 3 (below) shows the projected increase in GDP between 2017 and 2022, with and without carbon pricing. The vertical scale of the figure, which starts at $154 billion, makes the impact of carbon pricing appear dramatic, but this impression is coming from how the figure is constructed. The real difference between the two numbers is 0.45 percent. This isn’t zero, but it would be almost imperceptible if the figure had been presented in the conventional manner, starting at zero on the vertical axis.

What is the upshot from these three odd aspects of the PBO report? We need to assess the projected impacts of carbon pricing within the appropriate context.

Conceptual confusion in the Toronto Sun article

A second piece last week, from Anthony Furey at the Toronto Sun, is even more misleading. The article argues that the cost of carbon pricing in Canada will be $35 billion in 2022. This number is incorrect for several reasons.

First, this number is not even a good estimate of the revenues raised from a carbon price (although one of us used this as a quick-and-dirty number in the interview which formed the basis of Furey’s column, and we apologize for this confusion). With approximately 700 million tonnes of annual carbon emissions and a $50 per tonne carbon price, $35 billion would be raised if all emissions were priced. But most carbon-pricing systems apply to only 70-80 percent of total emissions, thus cutting down that number significantly.

Second, most carbon-pricing systems, including those in Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec, are designed to address competitiveness concerns of the business sector, and they do this by essentially returning some revenue to businesses based on their “emissions intensity”. This reduces the government’s net carbon-pricing revenue even further.

But the most serious problem with Furey’s column is that he confuses the “revenue generated” from carbon pricing with “the economic cost” of the policy. These are completely different things. The best measure of the economic cost of carbon pricing is the impact on GDP; as we saw above, this impact is very small. The revenue generated by the policy is quite different—especially if governments use it to generate economic benefits, which could include reducing other taxes. They could even follow British Columbia’s lead when their carbon tax was first introduced to make the tax “revenue neutral”; all revenues raised from the carbon tax were used to reduce personal and business income taxes.

Not only did Furey confuse these two concepts, but he assumed that governments used the revenues for … nothing. As Andrew Leach noted on Twitter, Furey’s article assumes that these revenues are “lit on fire.” We can and should debate how governments use their carbon-pricing revenue. There are lots of options, and the Ecofiscal Commission examined many of the trade-offs in its report on revenue recycling. But no government we know is planning to use that money to start a bonfire.

Don’t forget the benefits of carbon pricing

So far, we’ve only talked about the costs, but it’s just as important to consider the benefits. And carbon pricing does have clear benefits.

Most importantly, carbon pricing reduces GHG emissions. If we are taking our national target seriously—that is, our agreed contribution to the Paris Agreement and global efforts to fight climate change—we need new, stringent policies to achieve that objective. And every tonne of GHG emissions avoided has real benefits in terms of avoided impacts of climate change. Over the longer term, the costs of climate change are poised to be far greater than the costs of taking action to avoid them.

Reducing GHG emissions generates additional benefits, too. In particular, reducing GHG emissions tends to reduce local air pollutants that have serious health implications. The International Monetary Fund, for example, finds that countries (including Canada) could see important benefits from GHG policy in the form of avoided health and mortality impacts.

All climate policies have costs, but some cost more than others

Carbon pricing isn’t the only policy that can reduce GHG emissions, but it is the cheapest. In 2015, the Ecofiscal Commission used a complex model of the economy to compare the costs of carbon pricing with those of inflexible and intrusive “command-and-control” regulations. In both cases, the same amount of GHG emissions were reduced. The model’s projection showed that GDP would be 3.8 percent higher in 2020 if carbon pricing was used rather than the regulatory approach. This is an enormous economic benefit from carbon pricing—bigger than the size of the Canadian recession that occurred during the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

This result doesn’t mean that regulations are always bad. Well-designed and flexible regulations can do a better job than the standard, inflexible variety and come closer to—though not exceed—the cost-effectiveness of carbon pricing. And in those situations in which carbon pricing is difficult to apply, well-designed regulations can be used to complement carbon pricing.

Carbon pricing, regulations, or free-riding?

This brings us back to the beginning. Yes, carbon pricing, like all climate policies, will have economic costs. But that doesn’t mean we should take no policy action. Getting real benefits is worth incurring some costs. We need to figure out how to strike the right balance. What we need in this country is a better, more informed, two-part conversation around those costs and the benefits.

As always, we have important choices to make as a country. But in this situation there are really only three choices available.

We can choose not to take action, effectively free-riding on the actions of other countries, and then hope for the best.

Or we can choose expensive, technology-specific policies that might reduce GHG emissions, but do so at a high economic cost.

Or, finally, we can choose to implement flexible, low-cost policies (with carbon pricing being least expensive of all) to contribute to global efforts to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. We can design these policies to operate with the lowest possible cost and to generate genuine benefits through the careful recycling of revenues.

For those of us at the Ecofiscal Commission, the best choice seems pretty clear.

MORE ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE:

- Saskatchewan is launching a court reference that just might kill the carbon tax

- Nobody should believe Canadian politicians who promise to fight climate change

- For world governments, climate leadership is a matter of morality

- Alberta’s support of the national climate plan is nice, but hardly necessary