Why stock markets are so calm in the age of Donald Trump

A rare confluence of positives has created a buffer between Washington and Wall Street. But gradually, those positives will fade.

Traders work on the floor at the closing bell of the Dow Industrial Average at the New York Stock Exchange on November 15, 2017 in New York, as US President Donald Trump delivers a televised statement from the White House. / AFP PHOTO / Bryan R. Smith (Photo credit should read BRYAN R. SMITH/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

When did the Masters of the Universe become so Zen?

Much of the world freaked out over Donald Trump in 2017 in one way or another. But not Wall Street. Investors carried on enriching themselves and their clients like nothing unusual was happening in Washington. American stock markets have climbed steadily from one high to another, amidst an unusual level of calm.

That seems odd, given Trump’s attack on the established order. The war between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party never has been more intense. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Partisan Conflict Index, which measures federal political tension by counting newspaper reports of disagreement each month, jumped after Trump was elected. It then surged to a record in March, and generally has stayed above the highest levels reached during Barack Obama’s presidency, a period that featured the rise of the Tea Party and a government shutdown, among other things.

But it turns out the highly charged Obama years amounted to second-level chaos. Whereas Obama and the Tea Partiers were locked in a genuine ideological struggle, Trump takes a mad man’s glee in busting political norms and upsetting people. He quit the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement that would have revolved around the United States, and ordered the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement. He fired James Comey, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He disparaged the leader of North Korea, calling him “Rocket Man” and “short and fat.” We can debate how seriously one should take Trump’s baiting of Kim Jong Un (or vice versa), but for the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the possibility of a nuclear war is part of the zeitgeist.

Unlike the chattering classes, Wall Street appears more interested in what Trump does, and less in what he says. The S&P 500 Index had gained about 16 per cent this year, as of Nov. 24, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average was about 19 per cent higher. The Nasdaq Composite Index, heavy with the technology companies that some thought would do poorly under Trump, had surged almost 30 per cent.

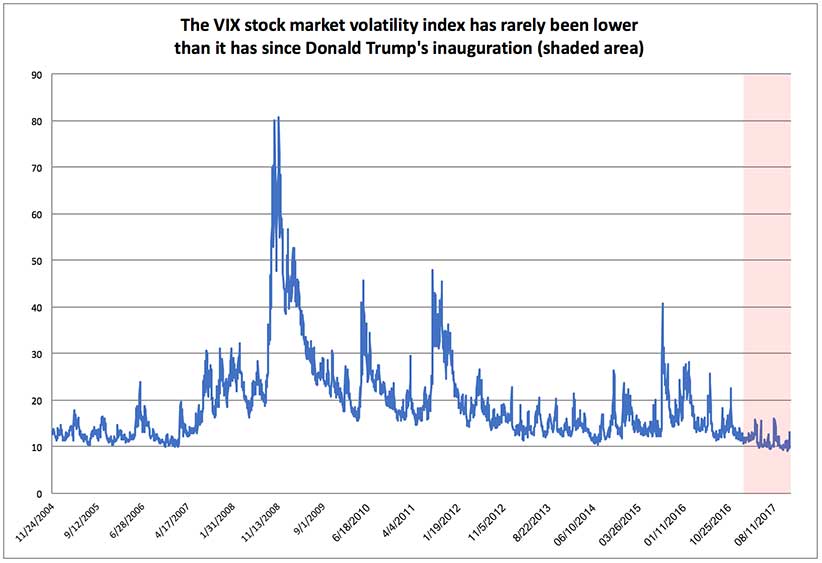

Those are steep increases, but if you were to plot the trajectory of those markets on a treadmill, you would barely notice the change in the incline. The Chicago Board Options Exchange, or CBOE, runs a volatility index known as the VIX, which is the index’s ticker symbol. It also is referred to as the “fear gauge,” as it is based on the trading of financial assets that allow investors to bet on future prices. You might have thought that Trump’s improbable election and his subsequent refusal to mellow in office would cause traders to worry about the stability of their investments. But there is no correlation between the VIX and the Philadelphia Fed’s political conflict index. In fact, the VIX rarely has been calmer than it was during the 12 months that followed Election Day.

Trump likes to take credit for all of this. “Great numbers on Stocks and the Economy,” the president said Nov. 17 in one of many tweets on the subject. “If we get Tax Cuts and Reform, we’ll really see some great results.”

After botching its attempt to repeal Obama’s healthcare law, the Republican majority in Washington now is attempting to rewrite the tax code in a way that would allow it to drop the statutory corporate rate to 20 per cent from 39 per cent. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin warned that failure to pass those bills would trigger a big slump. “To the extent we get the tax deal done, the stock market will go higher,” he said in an interview with Politico last month. “But there’s no question in my mind that if we don’t get it done you’re going to see a reversal of a significant amount of these gains.”

Maybe. Stocks tumbled earlier this month when the Senate’s tax writers tabled that would delay the corporate-income-tax cut until 2019. Then they rallied; the S&P 500 was about two per cent higher than a month earlier.

Republicans find it easier to rally around tax cuts than robbing millions of Americans of their health coverage. The House passed its bill ahead of schedule before the Thanksgiving break. The vote in the Senate will be tighter, but most observers seem to think Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will find a way to get it done. Alec Phillips, an analyst at Goldman Sachs, the investment bank, says there is an 80 per cent chance Trump will sign a tax bill by early in 2018.

FROM MONEYSENSE: How Donald Trump could trip up the bull market

Investors like the idea of corporate tax cuts because the companies in which they invest could become even more profitable. But it’s unlikely the tax changes are as important as Trump and Mnuchin seem to think they are.

Republicans talk of sparking economic growth rates in the range of four per cent, but models run by non-partisan forecasters, such as the Wharton business school at the University of Pennsylvania, predict only a modest increase over the shorter term. That’s mostly because few companies actually pay the top rate; once deductions and various legal dodges are factored in, the effective corporate rate isn’t far off the 20 per cent promised in the legislation. Also, virtually all objective analysis of the Republican plans suggests the tax cuts will widen the budget deficit and add to the debt. The Penn Wharton Budget Model predicts the added debt eventually would reduce economic growth, as money that might have been spent on productive investment instead ends up in the market for government bonds.

The more plausible explanation for the stock market’s success this year has less to do with Trump, and more to do with the woman he just declined to reappoint as chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen.

It took longer than anyone thought it would, but the Fed’s post-crisis policy of putting maximum downward pressure on interest rates finally is paying off. The U.S. unemployment rate was 4.1 per cent in October, near the lowest ever. Companies are broadly profitable, and the world’s biggest economies are growing in sync for the first time in a decade. The ultra-low-interest-rate policies of the Fed and other central banks means there is a lot of money sloshing around, bidding up financial assets. “The world economy is in the Goldilocks part of the cycle,” Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of Bridgewater Associates, one of the world’s bigger hedge funds, said in May. “All looks good for the next year or two, barring some geopolitical shock.”

It’s been interesting watching Dalio this year. He was initially positive about Trump’s victory, at least from an investor’s perspective. A Republican majority could be counted on to cut taxes and loosen regulation, he reasoned. But as the year progressed, Dalio became less keen. He openly worries that income inequality is making the U.S. harder to govern. Trump’s tactics only exacerbate those tensions, he says.

For now, a rare confluence of positives has created a buffer between Washington and Wall Street. But gradually, those positives will fade. Interest rates will rise. Debt will squeeze spending. Confidence will waver. Stock markets will fall. Eventually, there will be another recession. That is just how these things go.

And it’s at that point when Trump might really leave his mark. In August, Dalio advised that at least 10 per cent of any portfolio should be made up of gold to hedge political risk. “It seems to me that we are now economically and socially divided and burdened in ways that are broadly analogous to 1937,” he said. “I can’t say how bad this time around will get. I’m watching how conflict is being handled as a guide, and I’m not encouraged.”

MORE ABOUT DONALD TRUMP:

- Donald Trump pardons a turkey, and accused child molester Roy Moore

- Donald Trump’s ongoing struggle to distinguish female faces

- U.S. nuclear commander says any ‘illegal’ Trump orders will be resisted

- What the end of NAFTA could mean for jobs in western Canada

- Trump’s heartland biggest losers if NAFTA collapses, says business group

- The holiday season starts early for Donald Trump

- Louise Erdrich’s chilling portrayal of America as ‘a disintegrating country’

- Opioid crisis: Trump declared it an emergency, why won’t Trudeau?