Everyone’s mortgage is about to get more expensive

Get ready for a rate shock adjustment that is expected to accelerate in 2019

Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz speaks about the Financial System Review during a news conference in Ottawa, Thursday,June 9, 2016. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

The Bank of Canada raised its benchmark interest rate to 1.25 per cent Wednesday and signalled that, barring certain risks, more hikes are likely in the rest of the year. That’s creating an unusual situation for Canadians: for the first time in years, those renewing mortgages will be faced with higher rates and an increase in payments.

Even before Wednesday’s decision, five of the country’s largest banks hiked five-year fixed rates 15 basis points to 5.14 per cent last week. (CIBC is still offering 4.99 per cent.) In a country where consumers have grown accustomed to low rates, and where households are burdened with record levels of debt relative to income, this kind of change is worth noting. A recent survey published by insolvency trustee MNP Ltd. found 48 per cent of Canadian respondents were $200 or less away from being unable to fulfill their monthly financial obligations, an eight point increase since September.

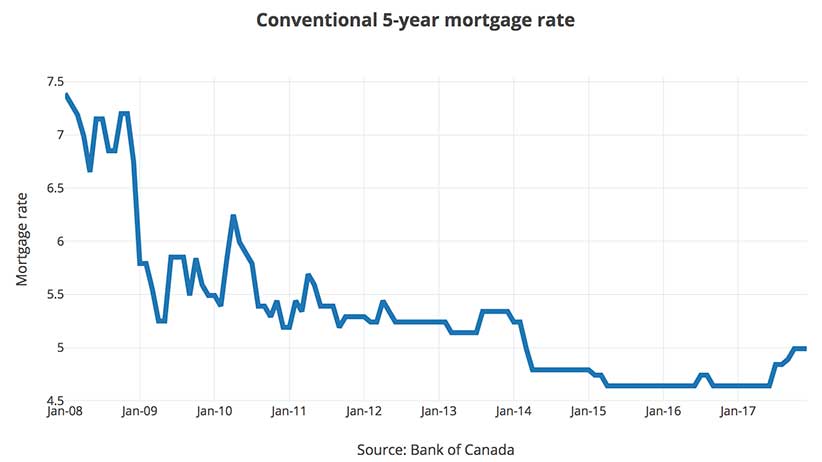

The below chart shows the conventional fixed five-year mortgage rate, which is an average of the Big Six banks’ posted rates, published by the Bank of Canada over the past decade. (Borrowers typically end up paying a lower rate than is indicated here, owing to discounts and special offers, but it serves as a useful gauge.) The trend for years has been falling rates—until the end of 2017, at least.

That trend extends back farther than 2008. Ben Rabidoux, president of North Cove Advisors, calculated that since the 1990s, consumers have seen an average drop of $91 per month on a five-year fixed rate mortgage for every $100,000 borrowed at the end of their first term. “With the recent rise in rates, we’re now at the point where the average consumer is seeing monthly payments rise at their first renewal, something we haven’t seen on a sustained basis since the early 90s,” Rabidoux wrote in Maclean’s last month.

The question for those facing renewal is how much more can they expect to pay? And more importantly, will they be able to manage?

In July, the Bank of Canada estimated that 47 per cent of residential mortgages with the Big Six banks will be up for renewal in less than a year, with another 31 per cent due in the next one to three years. On a mortgage of $225,000 and a gross income of $90,000, a one percentage point increase would increase monthly payments by $115, equivalent to 1.5 per cent of income. The central bank pointed out that highly indebted borrowers are more vulnerable. A household with a $360,000 mortgage and a gross income of $63,000, for example, would have to pay an extra $180 monthly, around 3.5 per cent of income.

Will Dunning, chief economist for Mortgage Professionals Canada, is not anticipating a steep increase in mortgage rates for those renewing this year, however. “Most renewals will be at similar or slightly higher rates than in 2013,” Dunning says. About 70 per cent of mortgages in Canada are fixed rate, with the majority of those loans set for five-year terms. In 2013, the average rate was 3.23 per cent. Current special offer rates are between 3.4 and 3.6 per cent, which is not a huge difference.

If the Bank of Canada ultimately raises its benchmark rate by 50 basis points from the start of the year, that could increase borrowers’ monthly payments by approximately 5 per cent, according to Rob McLister, founder of comparison site RateSpy.com. On a $200,000 mortgage balance, that works out to more than $50 per month. “That’s far from devastating, unless you’re in the minority having a significantly above average debt-to-income ratio,” McLister says.

Mortgages aren’t the only debt Canadians are saddled with, however, and the rates on credit cards, car loans, and home equity lines of credit could tick up as well, further increasing a household’s overall carrying costs. Many economists are also anticipating another one or two rate hikes in 2018. “The bigger impact will be next year, rather than this year,” says Beata Caranci, chief economist at TD. For Canadians renewing a five-year mortgage, the difference between rates in 2014 and 2019 will likely be greater than the 2013-2018 timeframe, especially if the central bank continues tightening. The good news is that any payment shock should be mitigated by rising incomes and increases in home equity, according to Caranci. “The more principle you’ve already paid down in the last five years, the more room you have to negotiate,” she says. “So it should be manageable.”

Of course, it’s not guaranteed the Bank of Canada will be able to hike a few more times. “What happens in 2019 or 2020 could unravel all the tightening being done,” McLister says. The biggest unknown is how NAFTA negotiations will play out. In its policy statement, the central bank noted that “uncertainty about the future of NAFTA is weighing increasingly on the outlook.” But the Bank of Canada has also indicated it’s not basing monetary policy purely on unknowns. Governor Stephen Poloz gave a speech in December about the three things that keep him up at night; NAFTA was not on the list. Instead, the Bank of Canada is focused on what’s actually happening in the economy, and many signs to point to higher rates over time.

“Households have been warned about rate risks for years. Delaying them further will only fan further excess as the warnings get ignored for longer,” wrote Derek Holt, head of capital markets economics, in a note on Wednesday. “That’s how we got into this mess by robbing savers to hand over to debt addicts. A rate hike is akin to an intervention.” Canadians should budget accordingly.