When the housing bubble bursts, there won’t be a soft landing

Although Canadians witnessed the carnage of America’s housing crash, many want to believe our housing sector will follow a gentler path

Condominiums are seen under construction in Toronto, July 10, 2011. Canada’s condominium boom, which has filled the skylines of its biggest cities with cranes and prompted a warning from its central bank, may well avoid the type of crash that has hobbled the industry in the past. Picture taken July 10, 2011. REUTERS/Mark Blinch (CANADA – Tags: BUSINESS CITYSCAPE CONSTRUCTION)

Share

The US housing market entered a bubble in the early 2000s and a few years later went into a tailspin, culminating in a crash. House prices dropped by 30 to 40 per cent, leaving many American homeowners owing more on their mortgage than the house value.

The recession that followed, the worst since the 1930s, left millions unemployed. In 2014, eight years later, their economy struggles still, with four million fewer people working full time. One of the hardest-hit sectors, housing and related activities, shrank from six per cent of GDP, bottomed at two per cent, and now is about three per cent.

Although Canadians witnessed this carnage from a front-row seat, many want to believe that Canada’s housing sector will follow a gentler path when it corrects, labeled by economists as a “soft landing”. Canadian lenders, homeowners with mortgages, politicians, construction workers, Toronto condo developers and real estate speculators hope that these people are right.

Let’s do a reality check.

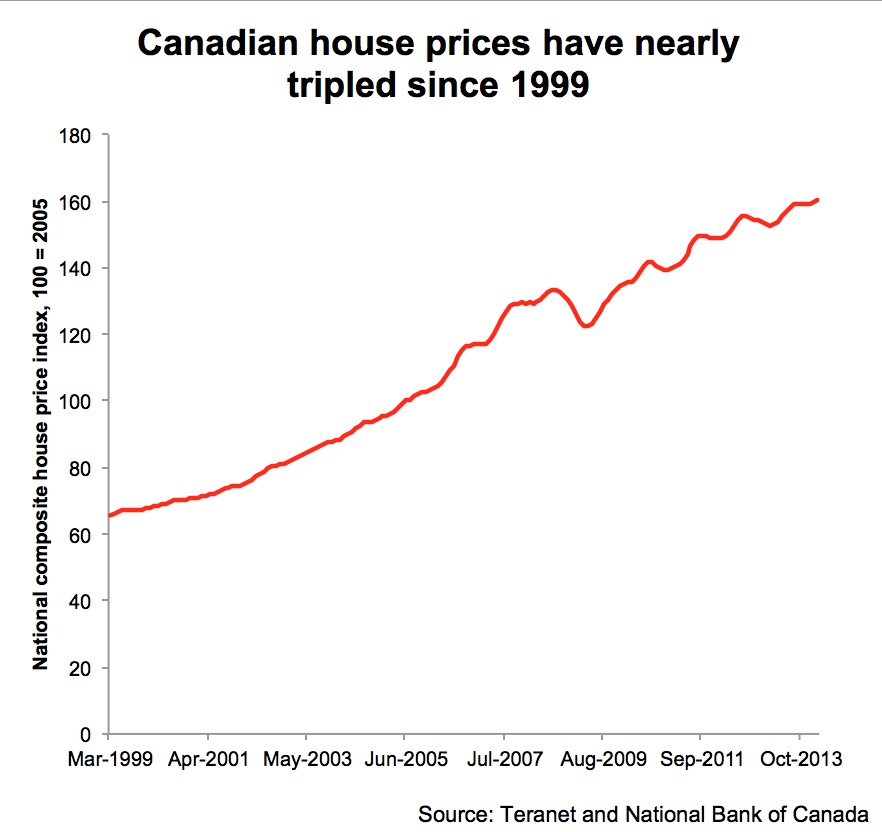

In the last twenty-four years the ratio of total Canadian household debt to disposable income has doubled, increasing from 80 per cent in 1990 to over 160 per cent in 2014. A similar US ratio peaked at 130 per cent. Canadian house prices grew even more rapidly, with the Teranet-National Bank Housing Index soaring to 160 at the end of March from about 60 in 1999, almost tripling. The housing industry employs more than seven per cent of all workers.

After-tax income growth for Canadian families lagged far behind house prices, growing from $51,000 (1990) to $63,000 (2011), inflation-adjusted. Families are managing to juggle enormous debts only with the help of record low interest rates.

So our bubble is as big as, or bigger than, the US version. But bubbles can last for a long time, and grow bigger before they burst.

What was the trigger for the US collapse? And what will happen in Canada?

The US meltdown started with a seizure in housing finance. The collapse began with Bear Stearns, and spread to Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Countrywide and many others. The catalyst that dried up the financing spigot was a loss of confidence in mortgage-backed securities and derivatives. Apparently none of the Wall Street bankers imagined that house prices could fall, or perhaps they thought that someone else would take the hit.

In Canada, house finance works differently as 75 per cent of the total $1.2 trillion in mortgages outstanding carries a government guarantee. This guarantee is for the lenders, and endorses mortgages with the government’s Triple A credit rating. Canadian banks can hold these mortgages with a zero risk-weighting. As a result, CMHC insurance underwritten soared to almost $600 billion today with another $300 billion in two privately-owned insurers, government guaranteed (90 per cent).

As long as the government (taxpayer) guarantees the loans, housing finance keeps flowing. Up until now it’s been all about the availability of credit, not the cost (interest rate).

What could go wrong?

- A recession would end the bubble. Unemployed people can’t qualify for a loan to buy houses.

- A US interest rate increase would force Canadian rates higher, and some first-time buyers couldn’t qualify.

- CMHC rules could be tightened further, in a belated attempt to protect the taxpayer, and lending would slow to a trickle.

- An exogenous event, economist jargon for an external event that isn’t priced into the market, could hit the economy, the housing market or the lenders.

What can Canadians do to prepare?

Only after the bubble bursts will we know if it’s a “hard” or “soft” landing, so the prudent stance is to assume the worst. The most important action to take, right now, is to pay down debt and to “Just Say No” to any new debt. If this means renting a house or condo instead of owning, that’s fine. There’ll be much better buying opportunities later, after the bubble bursts.

Hilliard MacBeth is a Portfolio Manager at Richardson GMP with more than 35 years experience in the Canadian investment industry.

The opinions expressed in this article are the opinions of the Hilliard MacBeth and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Ltd. or its affiliates. Richardson GMP Limited, Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund.