How these college programs retooled in the middle of a global pandemic

Video games, nursing scrubs at home, cardboard goggles and virtual welding. Ingenuity and improvisation allow students to train hands-on from a distance.

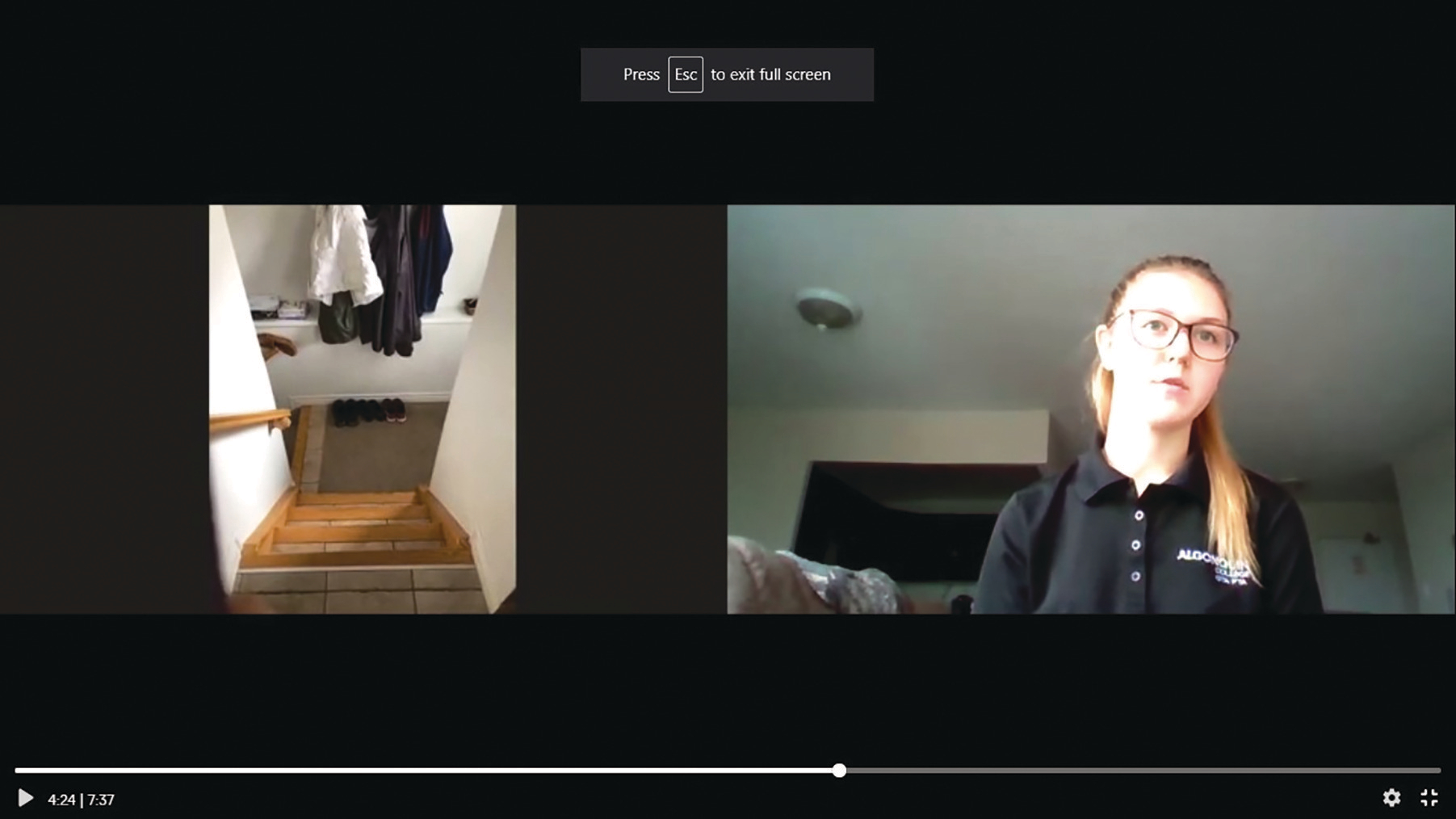

Stewart, a Bow Valley College nursing student, completing her lab exercises at home in June (Photograph by Candice Ward)

Share

The long shadow of COVID-19 has forced colleges to rethink how they deliver labs and clinics. With mostly online classes on offer this fall, colleges are devising virtual substitutes to equip students with skills for graduation.

Here is what hands-on learning at a distance looks like for some programs.

When school imitates play

When the pandemic hit in March, Sheridan College instructor Andy Alubaidy applied video game technology to build a virtual lab for his second-year instrumentation and process control course in electromechanical engineering technology at the college’s Brampton, Ont., campus. After watching his nephew, a university student, play video games, Alubaidy wondered, “Why wouldn’t you use this tool for education?”

From home, students use a computer keyboard and mouse to enter the virtual lab and walk up to four different machines with dials that measure and control liquid levels, fluid flow, air pressure and temperature. In hands-on exercises, students learn to analyze all aspects of instrumentation and process control, recording the results on a lab sheet for assessment by the instructor.

“It is a different way of experiencing the hands-on practice,” says Alubaidy, adding that the virtual environment simulates about 95 per cent of what happens in a real lab.

Miguel Morales Mejia, a student in the instrumentation course this summer, was initially skeptical. “How can you do a lab without any of the equipment?” he asked. But he adapted quickly, as he plays video games that use the same software as the virtual lab. “I was very surprised that the same thing that can give me endless hours of entertainment could also educate me.”

By taking the virtual lab, the international student from Colombia kept to his fall 2020 graduation schedule instead of risking delays on account of an uncertain return to labs on campus. The virtual environment also meant he could practise his skills at times convenient to him, not those set by the course schedule.

Alubaidy plans to introduce virtual labs in three other courses this fall, but notes, “We are not abandoning the physical lab.” He sees the virtual lab as a complement to traditional on-campus learning, once it resumes.

A kind of field hospital

At Calgary’s Bow Valley College, labs and clinics typically represent about 40 per cent of a two-year practical nursing diploma program. When the pandemic struck last spring, college instructors quickly reimagined all the program’s content in a virtual context.

“We put everyone on Microsoft Teams in a week, an amazing feat,” says Nora MacLachlan, dean of health and community studies.

Previously, nursing students purchased their lab supplies from the campus bookstore. For the virtual lab, Bow Valley delivered materials to the students at home. Instructors held regularly scheduled classes by video and filmed recordings of medical procedures for students to view on their own time. For evaluations, students uploaded videos of themselves performing the required procedures.

“Our virtual labs look exactly like hospital rooms and use the same equipment as in a hospital,” says MacLachlan. Students still wear nursing scrubs for their online classes. “They use all the same equipment as in a hospital, except now they are switching to a desk or kitchen table . . . or whatever flat surface they can use for their sterile procedure,” she adds.

Students sometimes improvised how to learn at home. Without an in-class mannequin, second-year student Victoria Stewart learned to insert an intravenous needle into a sponge and used tacks to elevate the IV tubing and bag to her kitchen wall. She could ask real-time questions of the instructor, or connect at any time through a chat box. Stewart liked the flexibility of the online lab because she had multiple practice runs before posting her video-recorded assignments for evaluation. Still, she prefers the human touch of the in-class lab, “with the instructor beside me coaching me through it.”

Visions of car repair

With lab space at a premium due to the pandemic, students in Vancouver Community College’s two-year diploma in auto collision and refinishing will train at home this fall. For a week at a time, each student will have a portable backpack equipped with software that creates an immersive environment in which to practise welding and car painting.

The pandemic was the “main driver” in purchasing the backpacks, says Brett Griffiths, dean of trades, technology and design at VCC. “We wanted to make sure these students still got some experience with these critical skills.”

In addition to buying licensed software, the college paid about $4,000 per backpack and $800 each for accompanying virtual reality headsets. Once traditional labs resume, the school will still use the backpacks. “Students can practise in the virtual lab before going down to the shop,” says Griffiths. “It is a much lower risk for students and they are not exposed to the smoke and fumes [of a traditional lab].”

Shelley Gray, chief executive officer of the Industry Training Authority that governs British Columbia’s skills trades, applauds the remote-delivery innovation. “We need to be cautious, but there are enough checks and balances in place [with simulated learning] that we are not setting students up for failure in the long run,” she says, citing the multi-stage approval process to accredit Red Seal apprentices.

New virtual modes of learning sit well with many employers, she says. “One of the consistent concerns from industry is how colleges, traditional in their approach, [have been slow] to keep up from a technology perspective.” Students in remote communities benefit, too, she adds, as they can learn from home instead of having to travel to the Lower Mainland for six to eight weeks at a time for classes.

Zooming in on fall prevention

The global coronavirus outbreak accelerated an emerging trend in health care—electronic long-distance communication between patients and health professionals—and a rise in employer demand for telehealth-savvy graduates.

With schools closed by the pandemic last March, instructors at Algonquin College in Ottawa looked for alternatives for in-person placements. They contacted occupational therapists and physiotherapists employed at agencies that normally offered placements to see if they would personally host a student at a distance.

In the new format, Algonquin instructors worked closely with the clinical therapists to develop and roll out activities for students in virtual placements and also provided weekly support to students. “We wanted to create as authentic an experience as we could working with community partners,” says Tim Tosh, coordinator of the occupational therapist assistant, physiotherapist assistant program at Algonquin’s School of Health and Community Studies.

Over four weeks, students used teleconferencing technology to conduct virtual sessions with a friend or family member who agreed to be a mock patient needing advice on how to avoid falls at home, for example. Over Zoom, the student instructed the mock patient to identify high-risk areas, such as the bathroom, submitting the video interaction to the clinical therapist supervising their placement. After that, mimicking the interaction typical in a face-to-face placement, the student and supervisor conducted a virtual discussion of possible treatment options. Then the student reconnected with the mock patient to outline potential home modifications and exercises to minimize the risk of a fall.

Because they are forced to adapt without access to face-to-face interactions, “students come away from this with better skills in therapeutic communication,” says Tosh. Working virtually, students had to make use of available resources in the home, such as substituting a water bottle for weights to be used in strength-training exercises. “This could happen in real life, we told the students, so what are the things you can find in a mock-client’s home to mimic the equipment they need?” says program instructor Danijela Subara. “They have to be creative to find the tools to provide the therapy.”

For evaluations, students used their phones to film interactions with patients and posted videos of their performance to instructors. “The professor could give immediate feedback to the student in a written or video format,” says Subara.

Tosh says that in the at-a-distance placements, the Algonquin instructors were much more involved with the clinical supervisors in the development and rollout of clinical activities to ensure students would meet their competency requirements. The online format “allowed us to be more involved in supporting the clinical supervisors because we could see the student’s submissions and answer questions as needed,” he says.

Algonquin instructors now plan to blend in-class and online clinics so students can practise the skills they need in face-to-face and virtual environments. “Let’s equip you with what you need to be successful because it is going to be hard when you are working,” says Tosh.

Up close with a jet engine

The cost of equipment and access to the internet are two concerns for colleges when delivering online labs.

“We have a lot of students who come with no computer or who are barely making it [financially],” says Marilyn Powers, manager of applied research and academics at Mohawk College in Hamilton, Ont. She advises instructors when to incorporate virtual reality and other technology in the curriculum. “We have lots of people who don’t have good bandwidth, and there are obstacles for them to get data on their phones.”

Mohawk sought out low-cost solutions, where possible. For example, for a course in the two-year diploma in aviation technician–avionics maintenance, a new online lab this fall will use virtual reality to help students learn the components of a four-stroke motor, a jet engine and other electronic devices of an airplane. Instead of expensive headsets, the college will use an app—made by EON Reality, a software company— embedded in cardboard goggles that cost about $10 to $15 each. Students place their phones inside the goggles (with side flaps to block out light) and look through the eye holes to see a 3D image of a motor engine. “We wanted something that was immersive and that students could use at home,” says Powers.

Instructors in the program are evaluating curriculum to identify content, such as safety procedures, that can be easily learned online compared to material that requires an in-person instructor, such as the modification of an actual instrumentation panel of a small aircraft. Powers says colleges can learn from the aviation industry, which, pre-COVID, won government regulatory approval to use simulators in training and now, with the coronavirus, increasingly looks to augmented and virtual reality as a substitute for in-person instruction. “Maybe it will take a little longer in education, but COVID just made the case for it much better,” she says.

This article appears in print in the Maclean’s 2020 Canadian Colleges Guidebook with the headline, “Learn to weld in the comfort of your home!”