We at Maclean’s get excited about democracy. I mean, who else would make a video eagerly anticipating the fall session of parliament and publish a post on five political stories we’re watching this week, just as our cover declares “Stephen Harper has finally met his match” in Mulcair?

Joking aside, not everyone is as enthused about their civic rights as we are, and some folks are trying to change that by pumping up the volume during Canada’s Democracy Week. In case you can’t make it to an event, we thought we’d share some of the wisdom smart people shared with us.

First, we gave you Max Cameron’s address at UBC on Why don’t more good people enter politics? Now, here’s Alison Loat, co-founder of Samara Canada, on what she’s learned about the power of asking. Join the conversation on Twitter: #demcda, #cdnpoli, @maconcampus and @SamaraCDA

Ask not what your country can do, but what you can do for your country.

This is among the most famous lines in the history of modern North American political speeches. Delivered on a cold morning in January 1961 by a young president who would live only another 34 months, it became a call-to-arms that rallied a generation into public service.

Pursue the Penguin Dictionary of Canadian Quotations and you’ll find no such rallying cries. “I love Canada because the politics are so dull,” reads one. “What the masses want are monuments,” said another.

Or how’s this?

“Bland works.” This said by Bill Davis, a much-loved premier of Ontario who served from 1971-85.

****

For a country that’s among the most educated and prosperous in the world, we know very little about our democracy, or the leaders who make it tick. Surveys suggest that only a small percentage of Canadians can name their MPs – but who can blame them? Did you know that after every election, on average, 1/3 of parliament turns over?

In a way, we’re in a perpetual state of frosh week.

Professor Cameron showed us some statistics that should give us all pause. In fact, last year, a pollster described Canadians’ relationships with their elected leaders like this: “there’s a fundamental disconnect between the everyday lives of Canadians and democracy. They look at what happens in the House [of Commons] and they don’t see themselves.”

And of course, look at our most basic form of democratic engagement – the exercising of our franchise.

An election is ultimately an expression of how we decide to live together. But only about 60 per cent of eligible Canadians voted in the last federal election. Provincial and municipal turnout is even worse.

And it is young people who are the biggest delinquents at the voting booth. That’s not all that new—young people have always voted in smaller numbers than their parents—but what’s changed is that as they get older they’re less likely to ever start voting.

Young and old, Canadians are disconnected from our Parliamentarians and more than ever, we’re simply opting out of politics. Full stop.

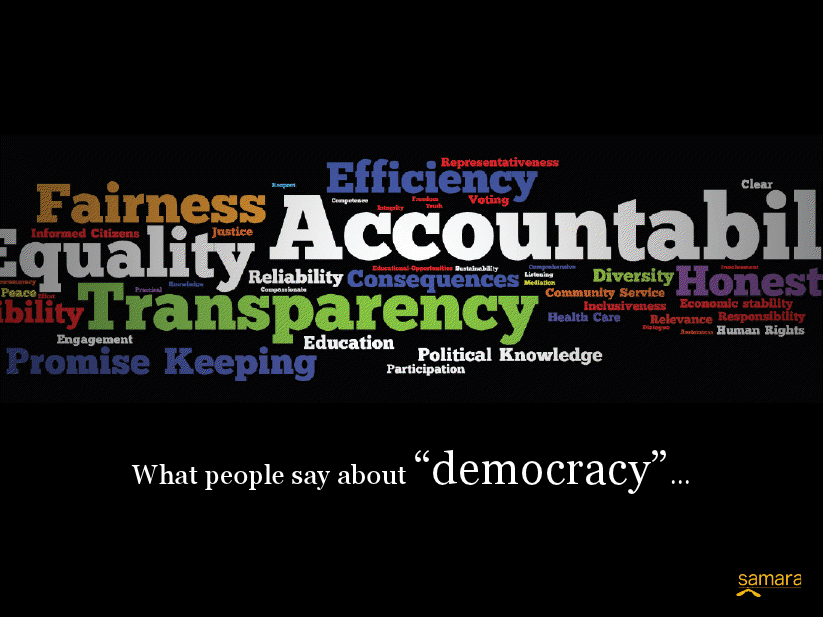

And this isn’t because Canadians are not democratic people. In fact, even those who don’t vote have positive views of democracy. The words on the screen are those used to describe democracy by groups of people who we spoke to who have largely decided not to stay home on election day. You’ll see that they’re nearly all positive.

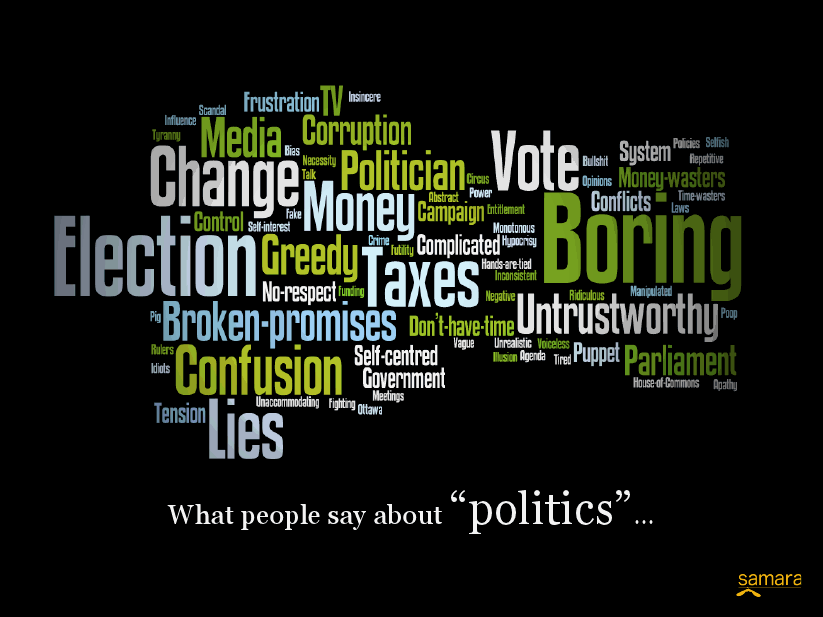

But look what happens when we asked them what came to mind when we said politics. A lot less positive. It’s almost as though they’re saying: “democracy I like, it’s the politics I hate.”

Said one young person we spoke to, “the system doesn’t care about me, so why should I care about it?” And another said, “It’s not like anyone cares what we think.”

Those comments illustrate a pretty fundamental point: that we don’t have a system that allows people, particularly young people, to see themselves reflected in it. Nor have we designed ways to allow for their meaningful input.

I hope I’m not alone in believing we can do better.

Better doesn’t require a massive institutional overhaul. Change could start much more simply.

What if we just started by asking? It’s strange, really, but one of the only time people are asked to participate is when an election comes around. And as our non-voting friends told us, by the time that happens, in their case, most of them had long ago decided it wasn’t worth it.

It seems simple. Almost obvious. But when were you last asked what you think?

I thought I’d share two stories about my own experience in developing creative ways for people to have a voice in the affairs of our country. I share them because I hope they’ll expand your conception of what you can do if you want to engage in Canada’s democracy.

And, of course, I’m going to ask for your help in making this happen.

The first is called Canada25, which I founded with a group of friends out of university. We sought to provide opportunities for young Canadians living around the world to engage together in Canada’s public policy challenges. We believed that without meaningful opportunities to contribute, young people would focus their energies elsewhere – to the detriment of our communities and country.

We started small – working through alumni associations and other organizations – to recruit a small team to help address how Canada could be a magnet for young talent. What happened, I think, was a small precursor to what internet now enables – much larger articulation of citizens’ desire to be involved – and we helped to organize and facilitate this interest.

The result of this project was a report called “A New Magnetic North.” It was on the cover of Maclean’s and was made into a documentary on CBC. So people paid some attention. Some of our work even ended up in the government’s Speech from the Throne.

But the bigger reaction was from the public. This was before web 2.0, Facebook or Twitter. I had hundreds of people emailing me from all over the world asking to get involved. We had problem – a good one – but weren’t sure what to do.

We were all volunteers, and the only way we could think of to practically involve all these people was to focus at the local level. So we started chapters, and decided to focus our next project on cities.

So it was, in response to the fact that we had no money and no other way of working, that we inadvertently developed what one of our alum, David Eaves, called “open source public policy.” We designed a process by which many people could participate, contributing what they could, when they could. We were built on networks, with a small team at the centre that designed the process and facilitated the participation, and we relied on groups of volunteers to do the rest.

We went on to produce several other policy reports in this fashion, including one on international policy, another on civic engagement and that earlier one I mentioned on cities. That report, called Building Up, was authored by one of our volunteers, Naheed Nenshi, in 2001. He used the report as the basis for his successful campaign to be mayor of Calgary two years ago.

So while Canada25 no longer exists, its themes are still resonate today. And that’s not because we possessed some particular foresight, but rather because we asked. And people responded. That experience set me on a path that led to my current role as the co-founder and executive director of Samara, a charitable organization that works to reconnect citizens to politics.

We started out doing research to illuminate, in new ways, this relationship between citizens and their political leaders. We conducted Canada’s first-ever series of exit interviews with former MPs – an opportunity to peek behind the curtain of our politics – the results of which we shared in a series of reports and curriculum materials you can find on our website.

Now we’re in the midst of two projects to re-imagine citizens’ role in our democracy.

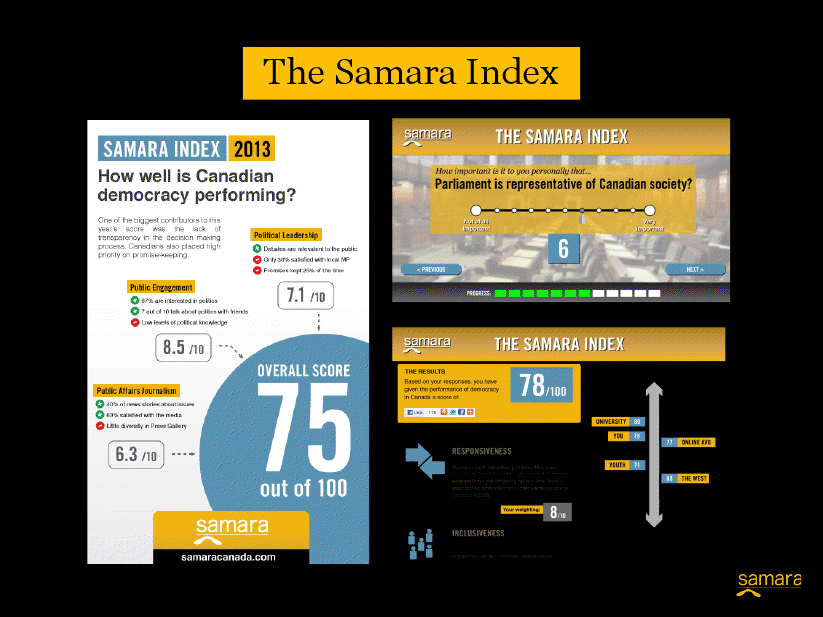

The first is an Index, which brings together never-before collected information to allow Canadians to participate in assessing and improving Canadian democracy.

It’s a bit like what the Maclean’s University Rankings did when it first started – making transparent information on how universities worked. This will do the same for politics, exploring some of the underlying reasons behind Canadians’ negative perceptions and the ways they’d like to contribute. We’ll also look at our political “infrastructure” – parties, MPs, Parliament – to explore where it works, and where it could improve to make it easier for citizens to engage with it.

It’s designed to be interactive. You can put in your own score and compare it to those from other parts of the country, other demographic groups and other well-known Canadians. We’ll ask you to share your score, via social media, and encourage your friends to do the same. We’ll suggest things you can do to help improve on the areas where we’re not doing so well, and bolster those where we are.

In addition to providing new information for critical stakeholders in our democracy – political parties, elected and government officials, not to mention citizens – we hope this provides an opportunity, for at least a few minutes each year, to reflect on the state of our democracy and how we can all be more active in it. In the coming months, we’ll need your help in testing some of the ideas, determining the right indices, and of course, filling out your score and sharing it with your friends.

The second is a program, designed in much the same way we designed Canada25, that works through community organizations to bring forward the voices of Canadians – particularly young people and people new to this country – to discuss their experiences with politics, and identify ideas for it could better reflect their daily lives.

We’ve begun this program in eastern Canada, with over 20 organizations signed up to work with us to organize these talks in their communities. But we need your help to extend it to western Canada and to British Columbia in particular. We need volunteers to help us organize discussions, analyze the findings, identify and champion the best ideas and extend the project online. With your election coming up, it is a good time to begin.

We hope you’ll visit us and let us know if you’d like to get involved. Just like Canada25 helped thousands of young people find their voice, connecting them to others who wanted to build stronger communities and a stronger country, so we hope this can help inspire a new kind of political participation.

But we do need your help. Here’s how to contact us.

Thank you.