Students take anti-depressants more often than any other med

What are universities doing to address growing mental health issues among students?

Share

On a Saturday morning at the beginning of this school year, a second-year student jumped from the window of his residence room at the University of Ottawa, an apparent suicide. As the details of the tragedy became clear, friends expressed how shocked they were by the death. In an excellent article written by Kelly Egan for the Ottawa Citizen, he was described as “a happy, motivated young man who travelled broadly, spoke several languages, had a leadership role at the residence and plans of entering law school.” How could this have happened to such a bright, promising young person?

The reality is that depression is incredibly common among students, especially those early in their university careers. Even the most ambitious and energetic students can be affected by depression and other mental health issues, and this often comes as a surprise to their friends and family of students.

The reality is that depression is incredibly common among students, especially those early in their university careers. Even the most ambitious and energetic students can be affected by depression and other mental health issues, and this often comes as a surprise to their friends and family of students.

Lev Bukhman knows all about what ails students. He’s worked with them for some 20 years, and is currently executive director of Student Care Networks, a leading Canadian health insurer that provides health and dental packages to over 450,000 students. Bukhman’s position gives him an insider’s view of what type of health problems students suffer with and medicate, and what he has noticed is more and more students struggling with their mental health.

“Mental health issues are one of the biggest challenges facing students today,” Bukhman says. In fact, anti-depressants are one of the most common medications taken by students. At most universities covered by Student Care Networks, anti-depressants are the number one drug, ahead of oral contraceptives and acne medication. Typically anti-depressants account for a third of drugs covered by student health plans. At one university—which Bukhman selected randomly from his files—35 per cent of all drug claims were for anti-depressants.

Although most universities don’t collect mental data about students, every counselor I spoke to said they’ve seen an increasing number of students seeking treatment for mental health problems. Statistics from the few schools that do collect mental health data are enlightening. At the University of British Columbia, 11 per cent of female and 13 per cent of male students reported in 2008 that they seriously considered suicide at least once in the previous year, according to Dr. Patricia Mirwaldt, director of student health services.

Suicide is not the only risk associated with the growing mental health issues on campus. Mirwaldt also noted that students reported that stress affects their academic performance more than any other issue, including colds, flus, sore throat and deaths in the family. “In fact, six of the top seven reasons students gave for academic difficulties were mental health related,” Mirwaldt wrote in an email. “Stress, sleep problems, depression and anxiety, concern for troubled family and friends, relationship difficulties and nonacademic use of the Internet.”

Bukhman believes that there are three reasons he has seen increasing numbers of students seeking help in the past 10 years. First, students are experiencing more competition and pressure to succeed in their academic careers, leading to increased stress. There are also more medications available now to treat students with anxiety and depression. Finally, stigma associated with mental health is lessening, which increases the likelihood that students will pursue help and take medication. And while it’s a good thing that more students are pursuing help, Bukhman believes counseling services at universities are overloaded.

Phil Wood, dean of students at McMaster University, identified mental health as one of the most serious issues his campus is currently dealing with. He points to three trends: “A greater incidence of significant mental-health issues, things like bipolar disorder and schizophrenia; students who are a threat to themselves or others; and a general decline in student mental health.”

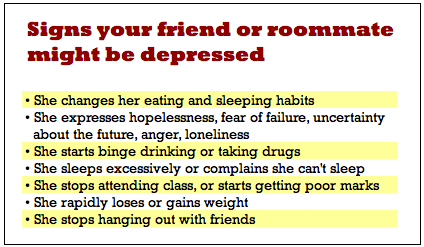

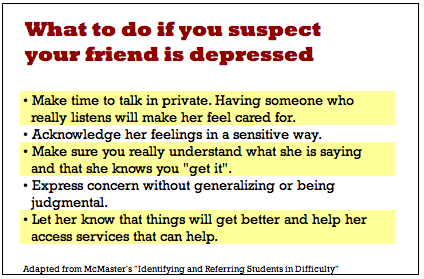

That’s why McMaster and other universities across the country are actively attempting to identify those who are struggling with their mental health and get them help. At McMaster, staff and faculty are given information to help them identify students who are experiencing difficulties, and assist in referring them. In extreme cases, when students may be suicidal or a threat to others, a behavior intervention team—which includes representatives from counseling, the chaplain, residence, security and so on—meet to discuss how to best approach the student and offer help.

That’s why McMaster and other universities across the country are actively attempting to identify those who are struggling with their mental health and get them help. At McMaster, staff and faculty are given information to help them identify students who are experiencing difficulties, and assist in referring them. In extreme cases, when students may be suicidal or a threat to others, a behavior intervention team—which includes representatives from counseling, the chaplain, residence, security and so on—meet to discuss how to best approach the student and offer help.

Some universities have recently implemented the QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer) Suicide Prevention Program. For instance, at Waterloo 1,400 students, staff and faculty have been trained to recognize suicidal tendencies and how to intervene. There are also counselors who work from academic and residence buildings so that they can reach students directly in the places where they live and work, rather than relying on the student coming into a counseling office.

Every university makes counseling available to students. What better time is there than during university—while counseling is free!—to work on one’s mental health? After all, students come to university to develop professionally and broaden their minds, and growing personally should also be part of the equation. University counselors are not only in the business of helping students with serious mental health issues, but also those who just want to improve their academic performance or learn to deal with stress.

For instance, Laurier’s counseling services brochure offers to help students deal with personal issues including assertiveness skills, roommate tensions, stress, homesickness, self-confidence, surviving a break-up, goal-setting, procrastination, perfectionism and the list goes on. Counseling truly offers something for everyone.

Erin Millar and Ben Coli are writing an advice book for university students. Email any questions or comments to [email protected].