First analysis of Martian soil turns up complex chemicals

Kate Lunau on what Curiosity has — and has not — found

In this photo provided by NASA’s JPL, this is one of the first images taken by NASA’s Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars the evening of Sunday, Aug. 5, 2012, PDT. It was taken with a “fisheye” wide-angle lens on the left “eye” of a stereo pair of Hazard-Avoidance cameras on the left-rear side of the rover. The image is one-half of full resolution. The clear dust cover that protected the camera during landing has been sprung open. Part of the spring that released the dust cover can be seen at the bottom right, near the rover’s wheel. On the top left, part of the rover’s power supply is visible. Some dust appears on the lens even with the dust cover off. The cameras are looking directly into the sun, so the top of the image is saturated. The lines across the top are an artifact called “blooming” that occurs in the camera’s detector because of the saturation. As planned, the rover’s early engineering images are lower resolution. Larger color images from other cameras are expected later in the week when the rover’s mast, carrying high-resolution cameras, is deployed. (AP Photo/NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Share

Curiosity, NASA’s one-ton robotic explorer cruising around Mars, has turned up complex chemicals in its first-ever analysis of Martian soil—finding water, sulfur, and hints of perchlorate, which some scientists think could serve as a food source for microbial life there. But the rover hasn’t yet found any carbon-containing organic compounds, a necessary ingredient for life, despite swirling rumours that such an announcement was coming.

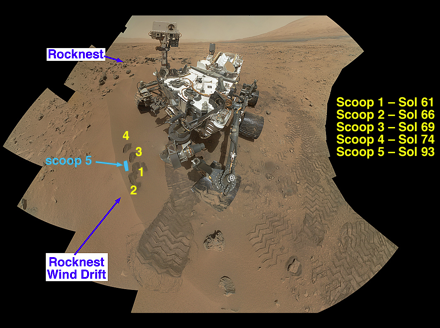

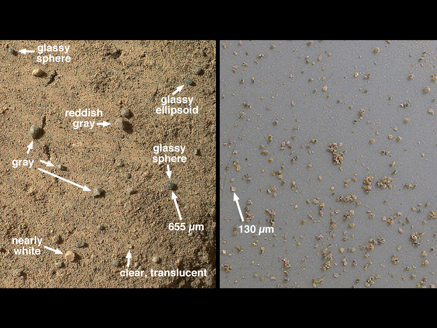

Curiosity is the first-ever Mars rover that can scoop soil into its instruments, then analyze them. It’s equipped with tools like the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM), which heats it up in a tiny oven to learn about it from the gasses it gives off; and the Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument, which measures the variety and abundance of certain minerals. This soil sample came from a windblown sand drift called “Rocknest,” in Gale Crater, where Curiosity touched down Aug. 5. (Its cameras have been capturing the site in stunning detail.) Canada’s contribution to the rover is an instrument called the APXS, about the size and shape of a Rubik’s cube, that can analyze the makeup of rock and soil samples.

A panel of NASA scientists delivered Monday’s news, including the University of Guelph’s Ralf Gellert, principal investigator for the APXS. And while they emphasized how exciting these results look—Curiosity’s instruments are “performing exceptionally well,” said Michael Meyer, lead scientist of the Mars Exploration Program, who compared the robot to a “CSI laboratory on wheels”—some space fans couldn’t help but find it a bit underwhelming. Their announcement followed widespread speculation that a major discovery would be unveiled, sparked by a recent NPR interview with principal investigator John Grotzinger, who said: “This data is gonna be one for the history books.” Unfortunately, he was talking about the mission as a whole—not hinting at the discovery of organic molecules, or little green men. (The Curiosity rover isn’t actually designed to hunt for life, The Guardian notes. Its mission is to find out whether Mars has the necessary ingredients to support life, or once did.)

Just because no Martian organics have turned up yet, doesn’t mean they’re not coming. Curiosity is only a few months into its two-year prime mission, and given the history of NASA’s last Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity—who kept exploring well beyond their mission’s expiry date—Curiosity still has a while to go. It’s slowly making its way to Mount Sharp, where scientists think water once flowed, but it won’t be there until next year. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the solar system, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft has found signs of ice and organics on sun-scorched Mercury, the planet closest to the sun, reminding us how little we still know about our planetary neighbourhood.