Hanging out on the road to the ocean

Abbotsford, British Columbia – Day 51

The Trans-Canada north of Lytton, BC

Share

Abbotsford, British Columbia – Day 51

Trans-Canada distance: 7,114 km

Actual distance driven: 14,650 km

NOW: (Hope) The fast way through from Kamloops to Hope is on Hwy. 5, the Coquihalla Highway. It’s four-to-six lanes all the way through, shaving 60 kilometres off the distance with a 110 km/h speed limit, and was completed in the mid-1980s when it was opened as a toll road. The tolls were ended in 2008.

This means that the Trans-Canada Highway in this region, which continues west for about 70 km to Cache Creek and then follows the Thompson and Fraser rivers south to Hope, is really more of a tourist route now than a commercial road. It’s the only part of the entire route across the country that’s been sidelined like this, but this is not a bad thing: the road twists through the canyons and offers fabulous scenery to drivers. It’s not the quick route, but it is the stunning one.

Just don’t be in a hurry. While there are plenty of three-lane overtaking sections, there are also plenty of sections where the two lanes are in the opposite direction, climbing a long hill, and double yellow lines prevent overtaking the slow moving lumber trucks and RVs that must descend more slowly for their greater weight and more challenged brakes.

Why was the Trans-Canada not redesignated to run along the Coquihalla when it opened, to follow the original directive of “the shortest practical route”? I don’t know – can somebody enlighten me?

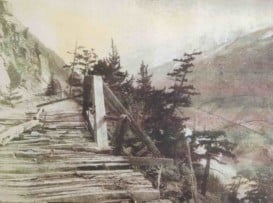

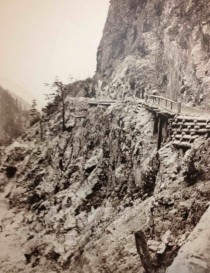

THEN: (Lytton) The roads through the Fraser River canyons were not designed for cars when Thomas Wilby and Jack Haney drove them in 1912. They’d been built a half-century earlier for wagon trains to bring supplies to the gold miners at Barkerville, and they were as basic and precipitous as they could be.

The two pathfinders, with a third man named Earl Wise, made slow progress to Lytton from Lillooet, continuing so late into the night that their acetylene tank ran dry, which meant they had no headlights. Their kerosene-powered parking lights were too dim to be of use, being up high beside the windshield, but they could not just park and wait for dawn because their car filled the entire road, blocking the way for the horse-drawn freighters that needed no lights.

Consequently, described Wilby in A Motor Tour Through Canada, Wise took one of the kerosene lights and “stretched himself at full length along the mudguard next to the outer edge of the road, reached out his arm so as to bring the lamp close to the ground, and boldly gave the signal “Go ahead!” Ten miles on one’s stomach, holding a light over a sheer drop of hundreds of feet is a devilishly unpleasant role! Inch by inch we crept on. Moment by moment the poor fellow grew stiffer. A sudden jolt and it seemed as if we must throw him down the bank. A flicker of the light, and it seemed as if we all, car and passengers, were already over the brink. We were incessantly rounding a series of bluffs, twisting and turning in short, sharp curves that shut out the road ahead. Conversation languished. The unfortunate man progressing on his stomach gave vent to his emotions only in occasional grunts.”

Eventually, they arrived safely in Lytton, where they had no choice but to put the car on a train south to Yale. The Canadian Pacific Railway was built through the Fraser Canyon on the site of the old Cariboo Road and it was not driveable. It would take the pathfinders only three more days to reach Vancouver; their night drive would be the final true challenge of their long journey.

SOMETHING DIFFERENT: (Hell’s Gate) British Columbians know the story of Simon Fraser exploring the region here in 1808, passing through the narrow and deep Hell’s Gate section of the canyon on wooden planks suspended by ropes from high above.

The road that finally made its way through the canyon was the Cariboo Road, which also literally hung off the cliff face in many of its steeper sections. It was used only by horse-drawn wagons, but it was important to keep the horses calm on the trail high above the river. When the railroad replaced it, tunnels were blasted through the rock to avoid hanging the rails out in mid-air.

These days, it’s a simple drive to Hell’s Gate but visitors still get to suspend themselves over the canyon. Gondolas drop 175 metres down from the road to the opposite side of the river, and a suspension bridge crosses back over the fast and deep water. The river here has three times the volume of Niagara Falls, apparently, and its crossing can still bring butterflies to the stomach.

SOMETHING FROM TRISTAN, 12: (Hell’s Gate) Today we went to Hell’s Gate just north of Hope on the Fraser canyon. It was okay except for the fact that you have to pay for just about anything there. Although they did have very good ice cream, especially the mint chocolate chip kind.

They also had a suspension bridge that went right over the water, which was pretty cool.

Other than that today was pretty great and I’m really happy because tomorrow we get to Vancouver, the city I’ve been looking forward to the most. Yaaaaaaaaaaah!!!!!