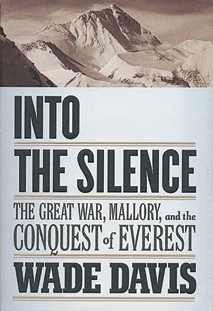

REVIEW: Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest

Book by Wade Davis

Share

It is a tribute not only to the power of Davis’s theme but to the grace of his writing that he has brought home anew, almost a century after it began, how unbearably sad the Great War was for contemporaries. A war like no other, it left Western Europe’s infrastructure largely intact, while blowing a gaping wound in its male demographic and an arguably larger one in its psyche. The British Empire emerged victorious, but at a cost its privileged elite were loath either to accept or to admit was too high. As mountaineer Geoffrey Young later wrote, witnessing the Western Front’s first gas attack shocked him more than the Second World War news of the Nazi death camps, “for then we still thought all men were human.”

It is a tribute not only to the power of Davis’s theme but to the grace of his writing that he has brought home anew, almost a century after it began, how unbearably sad the Great War was for contemporaries. A war like no other, it left Western Europe’s infrastructure largely intact, while blowing a gaping wound in its male demographic and an arguably larger one in its psyche. The British Empire emerged victorious, but at a cost its privileged elite were loath either to accept or to admit was too high. As mountaineer Geoffrey Young later wrote, witnessing the Western Front’s first gas attack shocked him more than the Second World War news of the Nazi death camps, “for then we still thought all men were human.”

One response to the war, from those in Britain’s climbing community who had survived it intact, was a series of attempts to scale Mount Everest, the world’s tallest peak. (Young, who had lost a leg to artillery fire, didn’t take part, although he later scaled the Matterhorn on a prosthetic.) The aim of the 28 men involved was both traditionally patriotic—they wanted to fly the Union Jack from the roof of the world—and, as Davis painstakingly shows, inchoately personal. A sense of cleansing redemption was in the air, and the very real possibility of death, to men who had survived the Somme, was scarcely worth mentioning. Ascending Everest was of no practical use, and that made it a “vindication of the essential idealism of the human spirit,” according to John Buchan, novelist, future governor general of Canada and ardent backer of the expeditions. George Mallory’s famous throwaway explanation for the climb (“Because it’s there”) fit their aims to an exquisite T, and so too did his equally famous disappearance—vanishing into the mountain mist on June 8, 1924, not to be seen again until his body was recovered 75 years later.