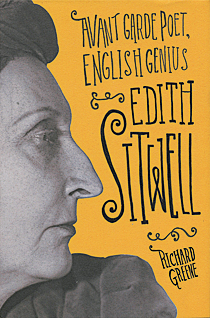

Review: Edith Sitwell: Avant garde poet, English genius

Book by Richard Greene

Share

Fifty years ago, Edith Sitwell was one of the U.K.’s leading poets. Today no one reads her. Small wonder that Richard Greene, whose new biography is the first in 30 years, has titled its prologue simply: “Why?” The reasons are many and at the same time one: her gender. “Of the great poets of her generation, Sitwell was the easiest to knock off the pedestal,” writes Greene, who teaches at the University of Toronto. “She was a flamboyant, combative aristocrat and, better still, she was a woman.” She could make it easy for opponents. Tall, ethereal, with an outlandish beaked nose and wild clothing, she was the epitome of the decadent Chelsea snob. Her barbs could confirm such charges—answering a nasty letter to the Daily Mail, Sitwell wrote that its author “has taught me the value of birth control for the masses.”

Fifty years ago, Edith Sitwell was one of the U.K.’s leading poets. Today no one reads her. Small wonder that Richard Greene, whose new biography is the first in 30 years, has titled its prologue simply: “Why?” The reasons are many and at the same time one: her gender. “Of the great poets of her generation, Sitwell was the easiest to knock off the pedestal,” writes Greene, who teaches at the University of Toronto. “She was a flamboyant, combative aristocrat and, better still, she was a woman.” She could make it easy for opponents. Tall, ethereal, with an outlandish beaked nose and wild clothing, she was the epitome of the decadent Chelsea snob. Her barbs could confirm such charges—answering a nasty letter to the Daily Mail, Sitwell wrote that its author “has taught me the value of birth control for the masses.”

Others dismissed Sitwell and her brothers, Osbert and Sacheverell—“the Sitwells,” as they were called, wielded much power in literary circles—as rank self-promoters. F.R. Leavis judged that they “belong to the history of publicity rather than of poetry.” Younger writers, like Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, reviled the high rhetoric of Sitwell’s poems.

She came by it honestly, and Greene’s account of her upbringing can be as surreal as her poetry. While at Eton, her father invented a “tiny revolver for killing wasps.” Her mother, who boasted Plantagenet blood, drank, gambled and was later jailed for fraud. The Sitwells and their Derbyshire manor may have inspired Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Sitwell never forgave D.H. Lawrence). Young Edith was made to wear a nose truss to straighten a crooked proboscis; there’s no evidence she ever had a sexual relationship.

Greene’s book is alive with the characters of 20th-century bohemia—from Gertrude Stein to Allen Ginsberg, Sitwell met everybody. She catapulted Dylan Thomas to fame, threatened to box his ears over his shenanigans, and was in New York days after his drink-saturated death. At a Paris reading, James Joyce declared himself “all ears for Edith.” Noël Coward walked out of another Sitwell recital. Being a woman forced her to be bolder than was safe. “There was no one to point the way,” she once said. “I had to learn everything—learn, amongst other things, not to be timid.”