Pauline Kael was fond of the ecstatic superlative. So here’s one for her: there hasn’t been a more famous and influential film critic before or since—with the possible exception of her former acolyte Roger Ebert, who wrote at her death, in 2001, that she “had a more positive influence on the climate for film in America than any other single person over the last three decades.” A queen bee in a boys’ club of film nerds, she sexed up a dry métier, embracing the sting of iconoclasm in films and as a critic. She was at the New Yorker from 1968 to 1991, but her star rose and fell with ’70s American cinema, as she heralded landmarks like M.A.S.H., Last Tango in Paris, Nashville and Taxi Driver. It was not just her opinions that stuck, but the feeling-out-loud performance art of her prose, which made everything personal. She was the new wave’s answer to the new journalism.

Pauline Kael was fond of the ecstatic superlative. So here’s one for her: there hasn’t been a more famous and influential film critic before or since—with the possible exception of her former acolyte Roger Ebert, who wrote at her death, in 2001, that she “had a more positive influence on the climate for film in America than any other single person over the last three decades.” A queen bee in a boys’ club of film nerds, she sexed up a dry métier, embracing the sting of iconoclasm in films and as a critic. She was at the New Yorker from 1968 to 1991, but her star rose and fell with ’70s American cinema, as she heralded landmarks like M.A.S.H., Last Tango in Paris, Nashville and Taxi Driver. It was not just her opinions that stuck, but the feeling-out-loud performance art of her prose, which made everything personal. She was the new wave’s answer to the new journalism.

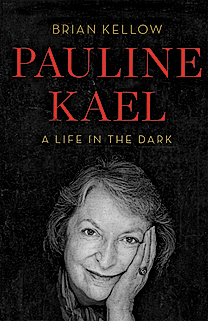

Brian Kellow’s richly detailed biography cements Kael’s stature but is no puff piece. He portrays her as a diva with a reckless grasp of ethics and “a Magellan complex”—she had to be the first to discover a director. Kael would cultivate friendships with the likes of Woody Allen, Sam Peckinpah, Robert Altman and Paul Schrader, only to turn on them later. And some of the critics she mentored, the “Paulettes,” would turn on her with Kael-like cruelty, notably James Wolcott. Kellow delves into Kael’s personal life, up to a point. (The serf-like way she treated her daughter, who typed up all her reviews, has a Joan Crawford ring to it.) Kael never wrote her own memoir, letting her 13 books of reviews and essays sum up her life. But this biography—which doubles as a vivid prism of American cinema—enlarges her voice with the panoramic context and sharp focus she prized in her own work.