The First World War united these Canadians by service and sacrifice

Their stories couldn’t be more different—from a wealthy socialite to a wandering Malaysian sailor. But they all served Canada when called upon.

Dawn rising on muddy, horrific battlefield of Passchendaele as soldiers tend to the dead during WWI. (Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Share

Munitions worker Mary Mays

As an 18-year-old, she undertook the dangerous, toxic work of manufacturing shells for the British

When Canada entered the war in 1914, it had very few professional troops and no munitions manufacturing industry. The first deficiency was quickly filled by volunteer citizen-soldiers, and later conscription. The second requirement was met with cobbled-together capacity. The 18-inch shells the British needed in the thousands for the war on the Western Front were soon being made in Canada, but without the necessary equipment or expertise. The country was “not producing enough shells, [and] the shells we do produce often failed to detonate,” explains Tim Cook, the author of several books on Canadian military history and a historian at the Canadian War Museum.

So the Imperial Munitions Board, headed by J.W. Flavelle, was set up in 1915 to oversee production and maintain standards. The armament industry eventually employed 250,000 people, among them 12,000 women, whom the board was particularly keen to recruit.

Mary Campbell was one of them, starting in Toronto at the age of 18. “My job was to use gauges to test pieces of work for 18-pounders,” she recalled in a later interview. “I tended 14 lathes operated by 14 women.” It was dangerous work. “The workers [were] handling high explosives and dangerous chemicals,” Cook says, and their skin would often turn a jaundiced yellow because of exposure to toxic substances. Their efforts proved crucial to the war effort. By 1917, about a third of all the shells fired by the British armies were made in Canada, Cook says.

After the war, Canada faced the challenge of transitioning a war economy back to a civilian one, as a few hundred thousand soldiers made the same shift. The Imperial Munitions Board was dissolved, and the country’s factories went back to producing consumer products. Canada was left once again without a domestic defence industry, and the women who had worked in the factories were without their employment. “The propaganda and the publicity of the war time was quickly forgotten, and they were shoved out of their jobs,” Cook says. Campbell married Joseph Mays, a soldier who had just re-enlisted for a second tour, on May 10, 1917. She kept his medals alongside her service badge, the markers of a couple’s contribution to the war effort.

The handiwork of the women—and men—who worked for the Imperial Munitions Board can still be found buried in the fields of France and Belgium. Thousands of shells, including ones manufactured in Canada, continue to work their way to the surface, where they’re still liable to explode, a now rather unwelcome sign that the early reliability problems were solved. “It’s a poignant legacy of the war that even though it was 100 years ago and everyone who fought is now gone, these shells remain,” says Cook.

—Murad Hemmadi

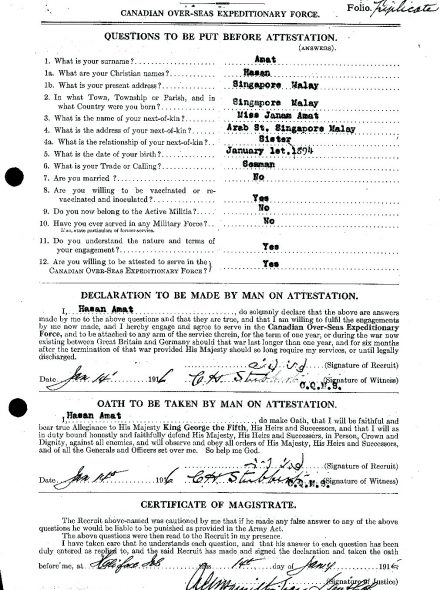

Private Hasan Amat

The soldier crossed an ocean to enlist, overcoming multiple obstacles to stay in the fight

During the course of eight days in August 1917, the Canadian Corps mounted a strategic bid to take Hill 70, the high ground north of the French city of Lens. More than 9,000 Canadian troops perished along with 25,000 Germans. The fight also drew some of their opponents’ focus, easing the pressure on their fellow Allied forces fighting the Passchendaele campaign to the north.

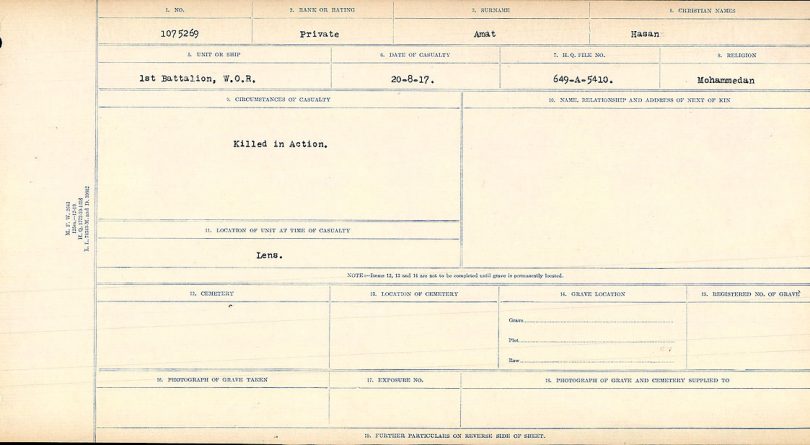

Among the Canadian fallen was a soldier who did not hold that citizenship, but who had made considerable efforts to be there fighting alongside those who did. Pte. Hasan Amat was killed in action on Aug. 20; his name is inscribed on the Vimy Memorial alongside thousands of others whose final resting places remain unidentified.

When exactly Amat arrived in Canada is not known. His stay was short enough that his first set of attestation papers from Halifax on Jan. 14, 1916, listed his present address as “Singapore, Malay.” In this he was not unusual. “There [were] a number of other nationalities who came to Canada to join [the war effort],” explains Georgiana Stanciu, executive director of the Royal Canadian Regiment Museum in London, Ont.

Amat’s occupation is recorded as “seaman,” which may explain how he ended up on the other side of the world. The forms list his date of birth as Jan. 1, 1894—likely an arbitrary day and month added to a more definitely known year—and his religion, written over one of the five Christian denominations on offer, as “Mohamedan.”

The association with the Royal Canadian Regiment did not stick—Amat was discharged on June 15. His file indicates he’d spent part of March in hospital, and his release from service was for medical reasons. Yet a different piece of paperwork simply labels him “undesirable.” Undeterred, Amat re-upped less than two weeks later in St. Andrews, N.B., joining the 4th Overseas Pioneer Battalion. The paperwork notes his prior service as “five minutes in RCR at Halifax.” Whether the wryness of that comment came from Amat, who between his two enlistments appears to have learned to sign his name in English rather than Arabic, or the recruiter whose handwriting fills the forms, is unknown. He had been in the country long enough to make at least one acquaintance, a J.M. McMillan of New Glasgow, N.S., who was to receive Amat’s worldly possessions through Amat’s sister, Janam Amat of Singapore.

In October, Amat sailed for France, only to end up hospitalized in Bramshott, England, with influenza, followed by bronchitis, then in Aldershot in 1917 with parotitis, a salivary gland infection. Still, his poor health did not prevent him from joining up with the 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion, to which he appears to have been transferred. They had all chosen to be there, repelling the German counterattacks on Hill 70, none more so than the seaman from Singapore who twice signed up to fight for Canada.

—Murad Hemmadi

Captain (Hon.) Mary Elizabeth Plummer

The daughter of a steel magnate, she rushed overseas to provide soldiers with the creature comforts of home

Mary Elizabeth Plummer’s father was a banker and steel magnate. Even as the Great War raged, leaving few families untouched, she presumably could have continued with some version of her life of privilege.

Instead, in her mid-30s, Plummer set off across the ocean almost as soon as the conflict began. She remained for the duration of the war, based at the Shorncliffe Army Camp on the southeast tip of England. As honourary captain of the Canadian Field Comforts Commission, Plummer coordinated the distribution of donated items such as socks, underwear, tobacco, books, magazines and sweets to soldiers at the front. But what she and her small band of compatriots really accomplished was maintaining a thread of connection between ordinary Canadians on the home front, desperate for some way to help, and the men trying to survive in the bloody muck of the trenches. Each care package that arrived was a reminder that somewhere, far from the thunder of war, someone was thinking of them.

Plummer, born in 1877, arrived at Shorncliffe on Sept. 27, 1914; just under two months later, she was appointed commissioner of the Canadian Field Comforts Commission with the rank of lieutenant. By August 1916, she’d been promoted to “temporary honourary captain.”

On Nov. 13 1916, Plummer filled out her attestation papers to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. She listed her father as her next-of-kin, her occupation as “none” and her present address as “Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe.” The medical examination section of the form was pre-printed with the phrase, “I consider him _______ for the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force.” Plummer crossed out “him” and wrote “her;” she was declared fit for service.

One wartime poster advertised Plummer’s commission as “the shortest way to send comforts from the HOME to the FIELD,” and solicited donations of goods and money. “Socks are always the most needed; shirts, medium-weight underwear, towels, handkerchiefs, sevenpenny novels and illustrated magazines are welcomed with joy,” the poster advised.

Between bouts of the terrifying violence we think of as encompassing the war, there was a surprising amount of downtime for soldiers, says Tim Cook, a First World War historian at the Canadian War Museum. Having pored over wartime correspondence as part of his research for his latest book, The Secret History of Soliders, Cook says Plummer’s supplies filled the quiet hours with tiny, normal pleasures. “What she was doing was important,” he says. “It’s absolutely crucial for morale. These guys are mired in the mud, homeless, being systematically killed, killing other men. Here’s a chance to hold onto some aspect of humanity.”

In August 1917, Plummer was “brought to notice of Secretary of State for War” for her valuable service, and commended again in March 1919.

After the war, she received her Certificate of Service, but once again on her form, a key phrase was altered. With the addition of a single typed “S,” it was noted, “She served in Canada and England with the Canadian Field Comforts Commission.”

—Shannon Proudfoot

Private Hilaire Dennis

Despite being conscripted into the war, he was dedicated to his duty

Hilaire Dennis travelled to the trenches of France and returned on a bloodied stretcher, a member of an often-forgotten and misunderstood group of Canadian soldiers: the conscripts who arrived by the thousands for the Hundred Days campaign that ended the war.

Dennis’s parents were French-Canadians who lived in Rhode Island when he was born; they moved soon after to the francophone enclave of Pointe aux Roches near Windsor, Ont. They died when he was in his teens, and he eventually found work as a streetcar conductor.

As the war raged on, new recruits were badly needed. “Though of fighting age, Dennis resisted the call to arms, reflecting a growing consensus against the war shared by French-speaking Canadians throughout Ontario,” his grandson, Patrick Dennis, a political science professor at Wilfrid Laurier University, wrote in a 2012 paper in the journal Canadian Military History.

On Aug. 29, 1917, the Military Service Act became law, permitting conscription. The policy gathered momentum in October with a royal proclamation published in newspapers across the country calling on unmarried men between 20 and 34 to register. But Dennis had already presented himself for a mandatory medical exam and been found fit.

By mid-February, he was in England for a basic infantry course, truncated because of how desperately new soldiers were needed at the front. In May, Dennis wrote to his aunt and uncle about his bitter disappointment when his unit departed for France and he was held back for the next draft, vowing that if given a shot at the Germans, he would “cut them down like hay.” “I am as ready as many other Canadian lads did to make the supreme sacrifice for my people and country,” he wrote.

By early June, Dennis reached France with the 18th Battalion for several more weeks of training; in mid-August, they headed to the front to provide badly needed reinforcements at Amiens and the Scarpe. After Dennis survived his first battle unharmed, he wrote to his aunt and uncle that prayers from home must have protected him from “the awful claws of this machine of destruction over here.”

The 18th Battalion would ultimately go over the top five times in 15 days, amid a furious series of assaults. Losses were heavy, and Dennis was among the injured, shot through his left hip. “Fritz opened up with his machine gun and it was just like a hail storm forced by a hundred mile an hour wind,” he wrote of the terror.

The war, for Dennis, was over; he would be treated for a bullet wound that blasted through his bone, and was eventually sent home in January 1919 after a months-long recovery.

In the end, Canada lost 11,423 soldiers in the Battle of the Scarpe, but, as Patrick Dennis would argue about his grandfather and others in Dennis’s position, the Canadian Corps withstood the loss in part because of reinforcements brought in by conscription. “No longer ‘shirkers,’ ‘slackers’ or even ‘conscripts,’ they were simply ordinary Canadian infantry soldiers,” he wrote.

—Shannon Proudfoot

Lt.-Col. Samuel Simpson Sharpe

A politician who raised a battalion but was long denied a memorial on Parliament Hill

On Dec. 17, 1917, the member of Parliament for Ontario North was re-elected in his riding by a two-to-one margin. He wasn’t there to celebrate. Lt.-Col. Samuel Simpson Sharpe was instead in northern France, observing an armaments demonstration. While other candidates campaigned, Sharpe and his unit, the 116th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, fought the Battle of Passchendaele, which ended with the Canadian Corps capturing the town of Ferfay. “He wasn’t knocking on doors, he was dodging bullets,” says Erin O’Toole, a veteran and the current member of Parliament for Durham.

Sharpe had assembled the battalion himself, raising it using men recruited in and around his hometown of Uxbridge, Ont. Unlike many of the high-numbered units that went over from Canada to France during the war, whose ranks were broken up and redistributed among other regiments, this one stayed together—almost certainly due to Sharpe’s intervention. “He was viewed almost as a father figure to these men,” O’Toole says. “He was the MP who gave the stirring speech that caused them to enlist.”

But many of those men perished on the battlefields of Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, Amiens and Passchendaele. Their deaths took a toll on their commanding officer. Sharpe wrote to the families of his fallen soldiers. On some of the notes, he used his letterhead from the House of Commons, scratching out “Ottawa” and replacing it with “France,” according to O’Toole.

The deterioration of Sharpe’s mental health is visible in these letters. “Were I to allow myself to ponder over what I have seen [and] what I have suffered thro the loss of the bravest and best in the world, I would soon become absolutely incapable of ‘carrying on,’ ” he wrote to one widow.

At the start of 1918, Sharpe won the Distinguished Service Order while in England undergoing officer training. He was hospitalized shortly afterwards. The disease listed in his personnel file was “general debility,” a term for unspecific feebleness that covered what later became known as “shell shock” and is now understood as post-traumatic stress disorder. “He understands the effect of his experiences in France and realizes that his ‘nerves quit’ him at times,” a doctor recorded on March 31.

Sharpe eventually returned to Canada, but never to Uxbridge. On May 25, 1918, he jumped out of a window at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital. Unlike Lt.-Col. George Baker, the other sitting MP to die during the war, Sharpe was not memorialized on Parliament Hill, at least partly because of the circumstances of his death, according to O’Toole. “They didn’t understand what he was going through,” he says, noting that the reconstruction of Centre Block following a fire in 1916 contributed to Sharpe being forgotten.

That’s set to change. In May, the House of Commons voted to install a bronze statue of Sharpe alongside one of Baker. O’Toole, who has led the effort to remember him, says he’s been assured by the government that a plaque commemorating Sharpe will go up in time for Remembrance Day. Sharpe’s life shows that trauma can “impact you if you’re a private with very little education . . . or if you’re one of the most prominent citizens of [your] day,” O’Toole says.

—Murad Hemmadi