Nowhere to buy

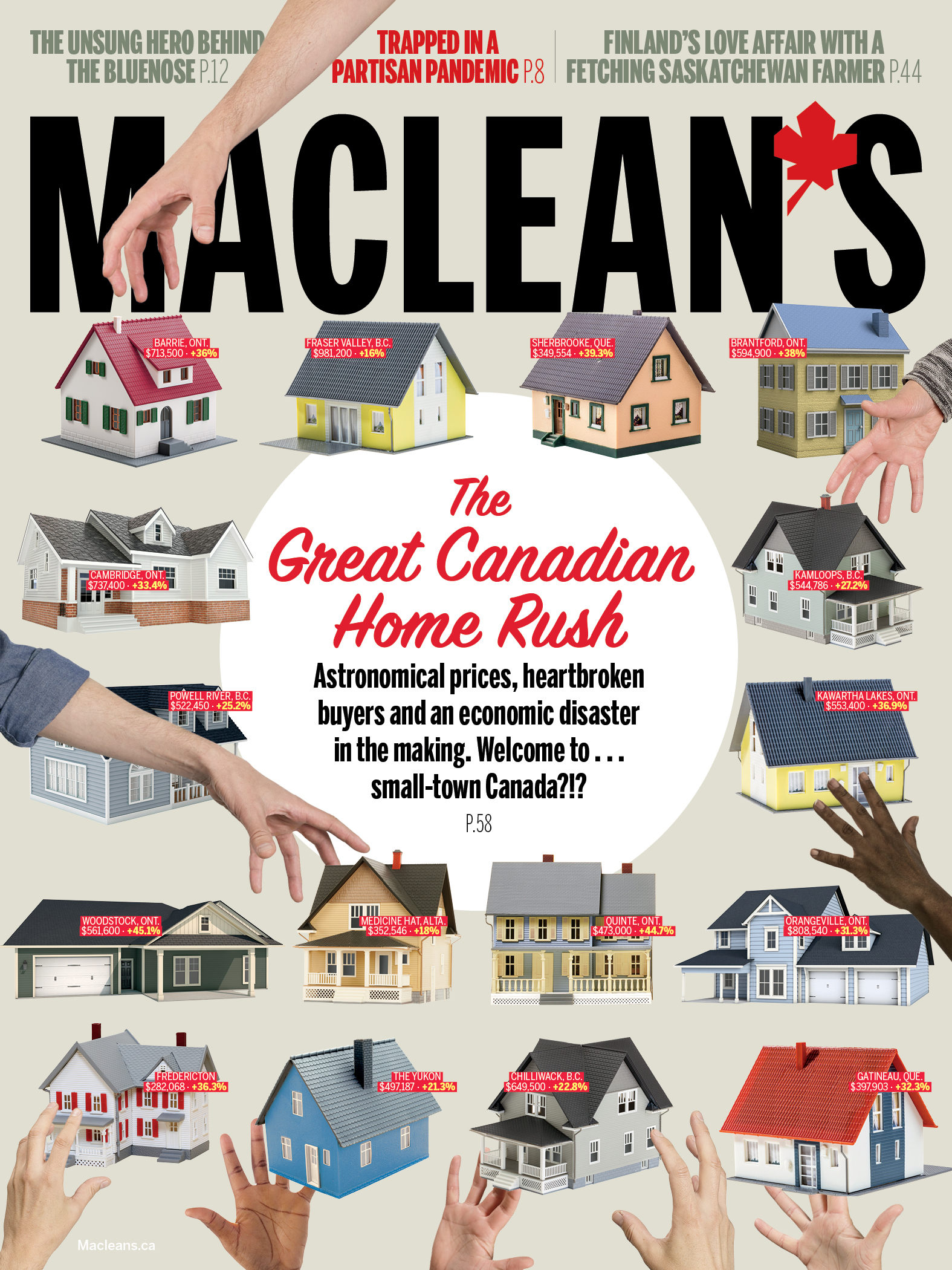

Soaring home prices, insane bidding wars and cancelled dreams have spread from urban centres into towns across Canada. How did everywhere become Toronto and Vancouver?

Kamloops, B.C.:

Three bedrooms, with a three-bed basement suite / Sold for $390,000 in June 2018 / Listed January 2021 for $499,900 / Sold March 11, 2021 for $560,750 (Photograph by Kathleen Fisher)

Share

It would keep happening, even though Louise Haehnel knew resisting her tendency to daydream would prevent more heartbreak. She and her husband, James, would view a house listed in Oshawa, Ont., or further afield. And she’d begin to imagine: the sofa here, the pictures there; six-year-old Aubree taking this bedroom and four-year-old Ava getting that one, instead of them having to share in the Haehnels’ small apartment. “Then, every single time, we’re disappointed,” she says, “because we’re not just a little bit outbid—we’re nowhere near in the running.”

James and Louise were learning to bid aggressively, even in Oshawa’s Durham Region, which had long been the most affordable region in the Greater Toronto Area, or perhaps the least scarred by the real-estate wars. When they began house hunting last fall, bidding $80,000 more than list price seemed to be common for anything within their $600,000 price range. As 2021 rolled around, prices kept soaring, and the Haehnels kept being blown away. What “really broke us,” James says, was bidding $195,000 above asking for a so-so, lower-priced house in a less desirable Oshawa neighbourhood, only to have 15 other would-be buyers top them. It sold at $302,000 over asking.

They kept looking for a few weeks, downgrading their standards from detached house to semi-detached, then to condo townhouse, and as far away as Port Hope, 50 km east of Oshawa. But prices kept ballooning—the benchmark price for a typical home in Durham was $666,500 in September, and $812,500 by March. “It’s disheartening and discouraging,” says James, 41. “And that’s when you’re like, what else can we do?” By early April, they’d decided to do nothing. Stop bidding. Stop looking. Stop daydreaming, except for a time when home prices fall back to earth. If they ever do.

James Haehnel and his wife bid $195,000 above asking on this Oshawa house, only to have it sell for $302,000 over asking; it ‘really broke us,’ he says (Photograph by Carmen Cheung)

The pandemic has left Canada housebound and surprisingly housing-crazed. Far from the recessionary crash many experts predicted, a brew of low interest rates, family savings that piled up during lockdowns and the rise of remote work have led to stretches of record-busting resale activity and prices. In response, major banks are once again calling for policy measures to calm the frenzy, lest the bubble pop with calamitous economic effect. But intervening will be a high-wire act, because Canada’s post-pandemic recovery depends heavily on a sustained housing boom. Worried as they are by the soaring prices and monster mortgages, financial and political leaders may shudder to think what economic recovery would be without them.

Unlike past surges, the most frenzied action is no longer concentrated in the epicentres of Toronto and Vancouver. Canada has become a nation of epicentres, as buyers from major cities hit smaller towns where, until recently, they could reasonably expect not to be priced out. The pandemic’s transformative impact on jobs and home lives has fuelled the trend. Liberated from their commutes by the mass shift to remote work, urbanites are looking further afield.

Many Western countries have hot housing markets during the pandemic, but not quite at the feverish levels of Canada’s. Last summer the benchmark detached-home price across Greater Toronto eclipsed $1 million for the first time, hitting $1.18 million by March, according to Canadian Real Estate Association data. That sent affordability hunters up and down every highway seeking property within their grasp. Now, a whole slew of smaller, once-sleepy housing markets in Ontario for the first time reached the half-million-dollar price mark for the typical stand-alone house: Peterborough, Simcoe, Woodstock, London, Niagara Region, Brantford. (In the latter three, the price sailed past $600,000.) “We’re seeing increases every month that historically you would have seen over a five-year period,” says Mike Moffatt, a business professor at London, Ont.-based Western University and director of the Smart Prosperity Institute.

There were similarly skyward prices throughout Canada in areas not used to them: from Kamloops, B.C., to Moncton, N.B.; from Montreal’s North Shore to Nova Scotia’s South Shore. Those with money and moving boxes are looking everywhere, and it’s creating whole new regions where would-be homeowners are struggling, or simply squeezed out.

James and Louise Haehnel didn’t expect it to be nearly that hopeless. Between his job at a security firm and hers in long-term care, their household income is comfortably above six figures, and family members helped plump the couple’s down payment. But they can’t win against all the people from Toronto now home-shopping in Oshawa, James says. “They’re able to bully people out of the market here.”

Balme Taninas has been a nanny for 10 years in Uxbridge, Ont., which is also located in Durham, socking away a bit each month for her Canadian dream: a house with a backyard suitable for the dog she’s always wanted. She and husband Rhanil, a cook, got within sniffing distance of that dream last year, getting approved for a mortgage and amassing a solid down payment. They conditionally bought the ideal house last spring in a nearby town for $449,000, but the inspection flagged a problem with a retaining wall, and they backed out. Then, as prices started to rise that summer, they got anxious, and Taninas recalls a friend’s warning: “You shouldn’t stop looking or else you’re going to get more and more behind.”

To chronicle their pursuit, Taninas used her YouTube vlog to broadcast her tours of homes, setting the footage to upbeat dance music. Later, with the soundtrack turned down, she would tell followers how she and Rhanil had offered their maximum available amount, $650,000, yet were vastly outbid. They couldn’t stay put in their snug apartment—it sat over a fish-and-chips restaurant whose exhaust fan blared all day and aggravated Rhanil’s inner ear disorder. So, in March, after months of frustration, they settled for a two-bedroom condo that cost more than the house they almost bought last year. It has a small patio space for a dog, should they get one. “If we can live here for five years, and when the market . . . ,” Taninas says, before trailing off. “I don’t know if it’s going to slow or go back to normal again.”

Taninas (right) and her husband, Rhanil, dreamed of a home with green space for a dog; after a long, frustrating search, they purchased a condo (Photograph by Lucy Lu)

John Pasalis, market analyst and president of Toronto-based brokerage Realosophy, recalls a recent message from a prospective homebuyer with an above-average income, who saved $140,000 for a down payment. She wanted to know what was available in the Greater Toronto Area—the suburbs, exurbs, small towns reaching from Clarington in the east to Burlington in the west, and north to Lake Simcoe—for under $700,000. Pasalis scanned sales records. If she’d been buying in the first quarter of 2020, 17 per cent of all Greater Toronto Area three-bedroom houses would have been selling within her range. This year, only three per cent are. Lower that limit to $600,000, and you’re talking just 130 far-flung or rundown homes among the more than 20,000 detached, semi-detached and row houses that have sold across the GTA, Pasalis says.

“It’s terrible. I don’t even know what to tell them,” he says. “They have a really good deposit, really good incomes. It’s just that house prices are so high they can’t buy anywhere.” The reality is, Pasalis adds, nobody can afford what they want around Toronto—clients are now shocked at how little they can get for even $1.5 million.

With a budget nearly that high, risk management professional Rahil Suleman is straining to keep up after a few months of looking to secure a home for his wife and three kids in the western suburb of Oakville, Ont. He’d hurriedly sold his Brampton townhouse in February after their newest daughter arrived. “We started looking at detached [houses] and prices have gone from $1.2 million and $1.3 million to being listed at $1.5, and going for $1.7,” he says. In mid-April, he saw a semi-detached he liked, but it sold at $400,000 over asking before bidding even opened. The clock’s ticking toward their townhouse sale’s mid-May close, so as of this writing, they were mulling Plan Bs. Maybe buying a temporary place until something ideal turns up. Or moving in briefly with his in-laws.

Suleman and his wife, a media company project manager, work remotely for now. But because of family and childcare arrangements, they’re reluctant to push their house-hunting boundaries too far.

Others have been, like never before. Toronto’s home-buyer exodus has spiderwebbed beyond Oakville and Hamilton and across southern Ontario. Tillsonburg lies 175 km southwest of Toronto, a 16,000-person manufacturing town whose faded tobacco-farming sector was popularized in a Stompin’ Tom Connors song. Prices have leapt by 40 per cent in the first months of this year, as big-city retirees and families seek more affordable properties.

(Photograph by Brett Gundlock)

The rapid onset of multi-bid wars and offers of $100,000 over asking has bewildered local buyers and agents alike. “The city buyers are more savvy. They’re used to dealing this way, where we aren’t,” says broker Barb Morgan. She tells local clients who lose out on a couple of homes they have to learn to bid way over. That, Morgan says, “has never been the mindset in Tillsonburg in my 23 years working.”

Initial fears were that the pandemic, coupled with the recession and unemployment that came with it, would depress housing demand and prices. And for a while during initial lockdown, activity did slow. But when society reopened last summer, so did the floodgates. Employment remained strong among those in upper-income tiers, notes Ben Rabidoux, president of market research firm North Cove Advisors. With vacations and restaurant dining shut down, household savings soared, emboldening families to upgrade homes or buy second properties. This kind of spending became even more appealing thanks to rock-bottom lending rates, which the central bank had set to limit the economic damage. Sales activity hit another all-time high in March, 75 per cent above the 10-year average, according to the Canadian Real Estate Association. And supply cannot keep up with this kind of demand, Rabidoux says, with active listings hitting a three-decade low: “You can’t have that dynamic and expect anything less than a face-ripping rally in house prices.”

Add in the growing crush of millennials, the oldest of whom turn 40 this year, and their desires to have kids and find space for them. “I don’t think that any municipality was prepared for the size of the millennials and the impact they would have as they entered the first-time-home-buying stage,” says Diana Petramala, senior economist with the Centre for Urban Research and Land Development at Ryerson University in Toronto. New homes are getting built at the fastest clip in more than a decade. But supply growth per person is nowhere near where it was when boomers were becoming first-time buyers, Petramala notes.

To make matters tougher for young families, the pandemic has left older Canadians leery of downsizing into supportive living or condo complexes, where they’ll be at closer quarters with their neighbours. That has further squeezed supply. Then there’s that other COVID-era revolution: working from home. At the same time as low interest rates drive down the cost of borrowing, many prospective buyers no longer have to factor the cost of commuting into buying a suburban or exurban home, notes Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser University’s City Program in B.C. “The fact you don’t need to report to your office is decreasing your transportation mortgage,” he says.

Yan has watched Vancouver’s home-price bloat push up costs across the Lower Mainland for years. But it’s reached places even he didn’t expect. One is Chilliwack, located 100 km east of Vancouver. To give a sense of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it dynamic in the Fraser Valley city, agent Aman Sanghera points to one of his own investment properties, which he sold for $475,000 in October. “Some realtor asked me in February if I knew the buyers,” he says, “because they wanted to offer $800,000.”

The snap-up sales and bidding wars have elbowed into the lumber mill town of Merritt, a 270-km wind up the Coquihalla Highway from Vancouver. About 90 per cent of purchasers in recent months are from the Lower Mainland, says agent Janis Post, and the half-million dollars that luxury homes in Merritt used to fetch is now the typical price. When locals inquire about selling, she warns them to make plans. “Because if we put your house on the market, it’s going to get multiple offers fast, and you need a place to go.”

The Atlantic provinces have long offered that alluring, lowest-cost option. Even in the Halifax area, you could get a family house for around $250,000. Well, you used to, before the pandemic, Michelle Soucy Rankin learned. She’s a Dalhousie University events planner, and a married mother of one who wants a second child and to move out of her aunt’s basement suite. With the help of family money, she and her husband, a machinist, raised their budget from $300,000 to $375,000, and they still constantly lose out on houses. The spreadsheet they maintain to track bids and selling prices has become columns and rows of heartbreak. “We’ve been saving and saving, and cutting back on everything. As soon as we’re ready to look, we’re just pushed out,” she says. Finally, in April, she found a way when her agent tipped her off about an offer on one house that had fallen through. She viewed and bought it that same day—at more than $100,000 beyond her initial budget. “If we ever wanted a home for our family,” she says, “we had to take the plunge.”

For many, though, that dream has evaporated. In a poll that RBC released in April, 36 per cent of non-homeowners under age 40 said they’d given up on the idea of buying a house. And people only see it getting worse: 62 per cent surveyed believe that a majority of Canadians will be priced out of the housing market in the coming decade.

The alarm bells and anxiety extend past those trying to compete in this market to those who analyze and monitor it. Even Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem has called it “worrying.” “Strength in the housing market is contributing to Canada’s economic recovery from the pandemic,” said the central bank’s analytical note from mid-April. “But it may also be intensifying housing market imbalances and household indebtedness.” Prices for homes 60 km away from Toronto’s core, the note observes, have risen at roughly twice the pace of homes 20 km away.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s market assessment, released in March, rated a majority of the large urban areas it tracks at moderately overheated, overvalued or otherwise vulnerable. “Highly vulnerable” markets include Hamilton, Toronto, Ottawa, Halifax and Moncton. (The CMHC’s assessment doesn’t cover smaller markets. Perhaps it should.)

Those with long memories think about the economically devastating U.S. housing crash more than a decade ago. Or about the late 1980s crash in the Toronto area: after more than doubling within three years, prices tumbled for seven straight years, bottoming out at nearly 28 per cent below the peak. Were such a massive price crash to occur now, that wouldn’t even put average prices in many regions back to their pre-pandemic levels.

But that scale of decline would leave many badly indebted homeowners underwater, and worse off still when interest rates and mortgage costs ultimately go up again. The squeeze could reverberate across the economy.

Major bank economists and other analysts have called for an array of measures to cool the exuberance, though almost everybody warns there is no silver bullet. In 2017, when housing prices last got market watchers spooked about a 1980s-style crash (mainly in Vancouver and Toronto), provincial governments tamed prices—largely with clampdowns on the foreign ownership that had surged in Canada’s top two markets. With its budget in April, Ottawa added a national tax on vacant homes owned by foreigners. “Houses should not be passive investment vehicles for offshore money,” Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said in her budget speech. “They should be homes for Canadian families.”

But while outside speculators may make convenient scapegoats for policy-makers, the COVID-era surge is almost definitely of Canadians’ own making. As Moffat puts it: “The reason Tillsonburg is going up is not because some oligarch in Moscow is listening to a Stompin’ Tom song and wanting to buy up the place.”

The independent federal Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions was first to signal changes in mid-April, proposing to slightly toughen the mortgage stress-test for would-be buyers with down payments large enough to secure uninsured mortgages. The changes, which would affect house hunters able to put down 20 per cent or more of the purchase price, would curb the risk of future indebtedness for some by effectively limiting their maximum budget. But few analysts expect this move on its own would cool the overall market.

There are calls, as ever, for added housing supply. The federal budget again boosted spending on affordable housing. Scotiabank even offered to contribute $10 billion over 10 years to build more. But when it comes to new conventional housing, the question in many regions remains where to build. Proposals to sprawl into green space, or construct infill family housing in existing communities, chronically stall in the face of resistance, be it rooted in environmentalism or neighbourhood huffiness. And timelines for getting new houses built are long—too long to address the current market froth.

Economists and analysts had put bolder measures on the table, including the third rail of Canadian real-estate measures—ending the capital gains exemption on sales of primary residences. But many observers warn that would further constrain supply by making elderly owners more reluctant to sell.

One potential option for federal or provincial governments (or even some municipalities): taxes to deter property speculation, as New Zealand did this year by taxing gains on quick property flips and eliminating mortgage interest deductibility for investment properties. Reforms to bring transparency and order to the purchasing process might help, too, so people aren’t left bidding wildly to beat mystery rivals. “The concern is you get these crazy bids that are way above the next closest bid, and then all the house prices in that neighbourhood are priced off this one crazy bid that was $150,000 over the next closest,” Rabidoux says. “That just feeds into this perpetuating cycle.”

So many tools available, but the Trudeau government’s budget played it tame: only affordable housing and the foreign buyer’s tax. Speaking to Reuters, BMO chief economist Doug Porter described the moves as “like a squirt gun next to a towering inferno.”

But political leaders, and homeowners watching their on-paper fortunes grow, surely appreciate the warmth that inferno gives off. This real-estate binge has gone a long way to lift the overall economy out of pandemic doldrums. By the end of 2020, investment in new housing, renovations and resales made up more than nine per cent of gross domestic product for the first time, and that was before the added rush to start this year. Ownership transfer costs—mostly real estate commissions—accounted for an astonishing 2.5 per cent of Canada’s overall economic activity, Rabidoux notes.

That may discourage leaders from tampering with a good thing, he says. Conversely, they might see it as a less productive use of investment capital, given how far investment in machinery, equipment, research and development now lags behind spending on homes. There’s another worrisome seismic shift: so many more well-paid young Canadians in so many more geographic regions facing a future where owning a home is unattainable. It could be time for policy-makers to re-examine priorities, Pasalis says. “We’re at a crossroads and they need to decide: do we want single-family houses to primarily be something that people can buy into and move into and live in? Or do we want this to be a lucrative asset class for both domestic and international investors?”

Because it’s not just pushing out first-time buyers anymore. Maclean’s spoke with Marc Iturriaga, a 46-year-old father of two who’s owned houses in Waterloo, Ont., and Calgary. He sold the latter last fall in a relatively tame but still buoyant market, after he was hired by Mohawk College in Hamilton as executive director of the student association. It’s a managerial position with a salary that puts him in the top 15 per cent of Canadians. But in recent decades, Hamilton has evolved from a working-class town to an affordable market for Toronto-bound commuters to—now—a place where Iturriaga couldn’t find anything that suited his family despite having a budget north of $800,000. That’s $300,000 more than he got for his much larger house in Calgary.

Iturriaga (left), his wife Emily, Evelyn, 12, and Bronwyn, 8, pack up their home in Calgary (Photograph by Leah Hennel)

Iturriaga was repeatedly outbid, pushed by sellers to bid even more and tempted at times to settle for houses his family didn’t like. He even considered forgoing the job in Hamilton. “It’s become this huge game now,” he says, “where all traditional methods of real estate dealings have gone out the window.”

So, after months of heartache, his family bought in Brantford, the next city over, a place listed at $599,000. He got it for $715,000—a fixer-upper he figures will take another $150,000 to renovate.

One of the first things Iturriaga did when he started at his college job, working remotely from Calgary, was give raises to all of his staff. If he hadn’t, he doubts he’d be able to recruit anybody who didn’t already live in Hamilton. Landing a house was a struggle for him, even after building up decades of home equity. If he’d been starting from scratch, he says, “it would have been cheaper not to take the job.”

James and Louise Haehnel, meanwhile, saw a slight opening during the April COVID lockdowns in Durham, and began looking again. This time, they were bidding above their old $600,000 comfort level. “We asked our broker to get us a higher approval and decided we can push it,” James says. These are the vanishing options of working Canadians who are still clinging to the home-ownership dream: push it financially, push outwards geographically, or get pushed out altogether.

This article appears in print in the June 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.