The Harder They Fall: Inside Canada’s gymnastics abuse scandal

Dave and Elizabeth Brubaker became top Canadian gymnastics coaches by pushing young girls to their limit. Their former

athletes say the tough training was a cover for abuse.

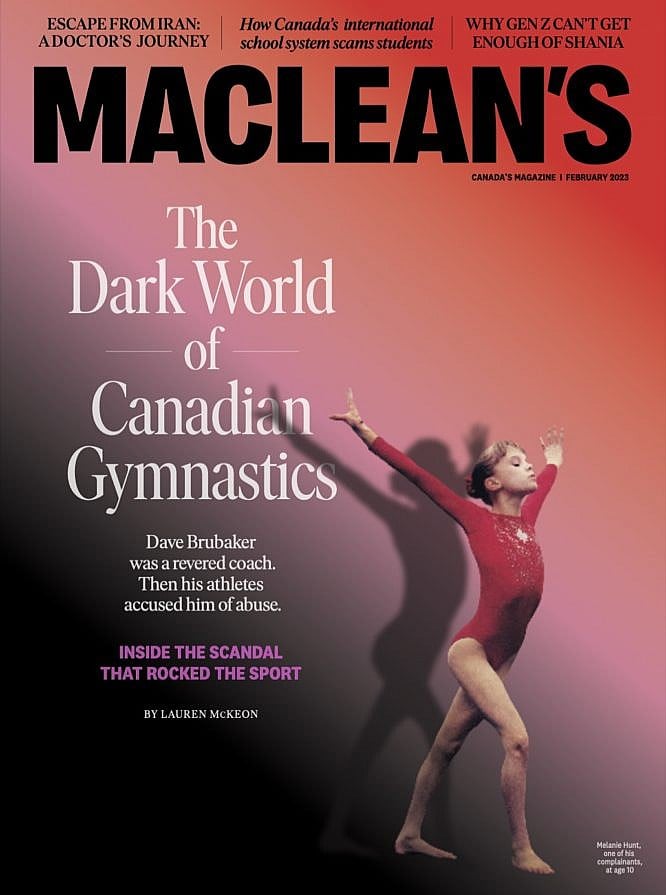

Melanie Hunt, shown here competing at age 10, filed a complaint that prompted an investigation into former Gymnastics Canada coaches Dave and Elizabeth Brubaker

Share

Abby Spadafora was two years old when she joined the Bluewater Gymnastics Club in Sarnia, Ontario. Her mother thought the sport would make a good outlet for her daughter’s abundant energy. Spadafora loved everything about the gym, especially flipping her little body into the foam training pit. By the time she was seven, in 1990, Spadafora was accepted into Bluewater’s competitive program and began training with the gym’s esteemed husband-and-wife coaching team, Dave and Elizabeth Brubaker.

Most days, she would wake up at six so she could practise for two hours before school, then leave class early so she could train for several hours more. The Brubakers told her she was on the path to a gymnastics career—and maybe, one day, the Olympics.

Spadafora craved the Brubakers’ approval, but it was hard to come by. They would yell at her if she didn’t master a skill or hesitated in a routine. As part of her training, the coaches measured Spadafora’s height once a week and her weight twice a day. Sometimes they used calipers to gauge her body fat. She learned to hang her heels off the scale to dip the numbers and hide the granola bars her mother packed as a snack.

When she was 11, Spadafora became the first Canadian to perform a difficult maneuver called a Rulfova—in which a gymnast launches herself backward from a standing position, twists in the air and lands seated in a straddle on the balance beam. But the Brubakers always asked for more. One time, when Spadafora couldn’t nail her routine the way Dave wanted, he became enraged and repeatedly pushed her from a handstand position off a five-foot-high bar. Each time she crashed headfirst to the ground.

Spadafora believed that the yelling and the fixation on her weight were normal parts of the coaching. She learned never to complain about her frequent injuries (the list included a dislocated finger, a broken foot and torn shoulder cartilage). Even as she feared the Brubakers, she also saw them as parental figures. If they pushed her, it was so she could be better. In 2000, when Spadafora was 17, Dave and Elizabeth relocated for two years to a gym with better facilities in Burlington, Ontario. Spadafora followed, boarding at their house.

Soon Dave Brubaker’s attention took on sexual overtones. According to Spadafora, Brubaker expected her and the other girls to greet him with a kiss. At training sessions, he would snap Spadafora’s sports bra. During a team trip to Taiwan when she was 17, he pulled her onto his lap while they were in the pool, placing her buttocks directly over his crotch, and tickled her. On the same trip, he entered her hotel room at 2 a.m., claiming that his roommate was drunk and he needed a place to sleep, then climbed into her bed and spooned her.

Spadafora knew what was happening made her feel awful and that it wasn’t right, but she couldn’t process it as abuse. She loved being a gymnast, loved being a competitor. Then at night she would cry herself to sleep, thinking she’d done something wrong, dreaming of escape from the gym. “Looking back,” she says now, “I was in complete survival mode.”

Abby Spadafora, now 39, began training at Bluewater at age two. Here, she’s pictured at a competition in 1997 (right), stretching with Elizabeth (far left) and with Dave in 1997 (bottom). (Portraits by John Kealey & Jackie Dives.)

In 2002, she left Bluewater to join the gymnastics team at the University of Arizona, where she had an athletics scholarship. Three years later, after suffering a back injury, she dropped out, returned to Sarnia and got married. She tried working as a coach at Bluewater, but left because she couldn’t bear being so close to Dave Brubaker. As an adult, she rarely spoke about what she refers to as her “gym days.” She told her husband, her sister and a therapist only the barest details. Then, in October of 2017, she received a call from the Sarnia police. Melanie Hunt, a 35-year-old health-care worker and a former Bluewater athlete, had filed a complaint about Brubaker. She had named Spadafora as a possible fellow victim. Spadafora told the officer that he was “opening a can of worms.” Abuse was so endemic within gymnastics, she felt, that one case would unearth countless others.

She was right. Eleven women, including Spadafora and Hunt, came forward to share similar stories of abuse at Bluewater. Women alleged Dave Brubaker kissed and fondled them, some when they were as young as 12. They say he screamed at them, repeatedly called them fat, and forced them to perform dangerous moves that resulted in injuries. They say they were manhandled into painful positions—their bodies stretched, yanked and pushed beyond what they could endure. The Brubakers denied any wrongdoing.

The case is one of many prompting a widespread reckoning within gymnastics, as parents and athletes question why this notoriously high-pressure sport attracts and tolerates abusive coaches. The crisis was a long time coming and, by many measures, inevitable. Gymnastics’ problems don’t end with a pair of coaches or a single gym—it’s infused into the DNA of the sport itself. The question now is not simply whether it can be made safe for thousands of young girls, but whether it deserves to be saved at all.

Perhaps more than any other sport, gymnastics burdens children with expectations of extreme excellence. Many kids begin as young as 18 months and, like Spadafora, start training competitively by age seven. A coach can have an overpowering influence on how a young athlete views herself and her self-worth. This dynamic leaves kids in an impossible position: even if they’re being mistreated, speaking up could risk everything they’ve worked for, including an identity formed around the sport.

The notion that ideal female gymnasts should be young, thin and lithe took hold in 1976, when the tiny 14-year-old Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci scored a perfect 10 on the uneven bars at the Montreal Summer Olympics. The feat—something no Western gymnast had done—ushered in what one journalist at the time called the “attack of the mini-monsters.” Gymnasts in North America and Western Europe started competing at much younger ages and attempting infinitely more daring handsprings and mid-air twists. Soon, girl gymnasts were idealized as the perfect mix of precious and powerful, feminine and determined. They wanted to be the next Comaneci or Mary Lou Retton or Natalia Yurchenko. In competition, they sparkled and shone and, as they performed incredible athletic accomplishments, they always smiled.

In Canada, more than 250,000 gymnasts are registered with the national athletic body, Gymnastics Canada. The organization was established in 1969 with the express purpose of advancing the sport and putting Canadian gymnasts on the world podium. Based in Ottawa, it has a board of directors, 13 staff and, in 2022, a $5.6-million annual budget. Ian Moss, its CEO since 2018, previously held management and leadership roles at Rowing Canada, Speed Skating Canada and the Canadian Olympic Committee.

GymCan, like so many athletic organizations, exists to train athletes for the podium. Winning means more fame and funding for the sport. This comes with a potential conflict: an organization incentivized to pressure kids to perform better, higher, faster is also responsible for their well-being and policing its own glory-seeking coaches.

While preparing athletes for the Olympics, GymCan, in partnership with its regional partners, directs education and training for coaches and judges, shapes its gymnastic programs, and manages any complaints brought forward by gymnasts in the country. Athletes and GymCan-accredited coaches must sign a code of ethics that covers anti-doping rules and anti-racism policies and prohibits abusive and sexual behaviours. If anyone is reported to have violated the code, it’s up to GymCan to decide whether to investigate or dismiss the accusations, and what punishment to dole out if it determines they’re substantiated. In other words, GymCan has historically had complete power to make, arbitrate and then enforce the rules.

Moss estimates that the organization vets two or three complaints about safe sport violations per month. In the four years that he has been CEO, 13 complaints have triggered a full investigation and disciplinary process. Some of those involved sexual assault and misconduct charges against underage gymnasts. On its website, the organization discloses basic details about disciplinary decisions and a list of suspended or expelled coaches (a total of 31 since 1996, the year GymCan started collecting such data).

Along with gymnastics, several other sports are facing a wave of abuse allegations. Last March, bobsled and skeleton athletes wrote a public letter calling for the resignation of their national federation’s president and of its high-performance director, citing a culture of fear. Two months later, more than 100 boxers signed their own letter, calling for the resignation of Boxing Canada’s director. They wrote, in part, that any athlete or coach who spoke out against physical and psychological abuse often found themselves sidelined from competitions. And in October, the CEO and entire board of Hockey Canada resigned after allegations of sexual assault surfaced against members of the World Junior team—and complaints of a corresponding culture of silence and cover-ups.

Last October, following the public furor over both gymnastics and hockey, federal sport minister Pascale St-Onge began toying with the idea of a full public inquiry into the country’s sporting organizations. She also catalogued accusations of mistreatment, sexual abuse or misuses of funds directed at eight national sports bodies, including rugby and rowing. Until now, abuse was tolerated as the price of victory.

***

The barn-like main facility at Bluewater Gymnastics is lined wall-to-wall with blue gymnastics mats and training equipment. Over the years, it’s been decorated with mementoes from the Brubakers’ triumphs: flags from the 2007 Pan American Games in Rio, the 2011 Japan Cup, the 2012 Olympics. For 34 years, Bluewater was the Brubakers’ second home.

Dave and Elizabeth met in the 1980s as students in the gymnastics coaching program at Toronto’s Seneca College. Dave, a sporty teen, had started coaching part time at a local club in Waterloo during high school, mostly because he needed a job. He fell in love with gymnastics and, soon after, with Elizabeth—a gymnast since age 10 who grew up in Scarborough and had also coached in her teens. After the new couple graduated, they searched for a club where they could coach together. In 1984, they landed jobs at Bluewater Gymnastics, which is run as a non-profit. Dave soon became the head coach.

After his arrest, Dave Brubaker wrote an apology letter to his wife and the complainants. “I am guilty of crossing the line,” he stated. “But I want you to know that my intentions weren’t sexual or premeditated.”

Next came marriage and two sons. Both Brubakers were well-liked, thought to be trustworthy and committed. While they were busy shuttling their athletes to competitions across the province, their athletes’ parents babysat the Brubakers’ kids, creating a close-knit gym community. When the two left town for Burlington in 2000, Bluewater secured funding from the city to upgrade the facilities and woo them back in 2002, offering Dave a job as gym director and Elizabeth the role of program director.

Their gymnasts placed consistently on the podium at provincial and national events, and there were some, like Spadafora, who performed notably difficult skills. In 2012, 18-year-old gymnast Dominique Pegg, under Dave’s coaching, made the national team and competed at the Summer Games in London—the first Bluewater athlete to make it to the Olympics.

Before the 2012 Games, Canada’s gymnastics team was never on the level of major players like the U.S., China, Romania and Russia. That year, however, Team Canada finished a historic fifth in the all-around competition, only four points behind China. Not only was it Canada’s best-ever showing at women’s gymnastics, it was the first time the team had made it to the finals since the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, when the Soviet Union and the entire Eastern Bloc sat out the competition. To the team, and to a thoroughly charmed Canada, the fifth-place finish was as good as gold. Pegg herself finished 17th—the fourth-highest ever by a Canadian gymnast in a non-boycotted Games. Justin Bieber congratulated her on Twitter.

In 2014, GymCan gave Dave Brubaker an award to honour his long-time service and recent success. That same year, it named him the national director of the women’s artistic gymnastics team, officially handing him power over female Canadian gymnasts’ Olympic dreams. Brubaker told the Sarnia Observer that he had hesitated to take the influential position because he didn’t want to spend so much time away from Bluewater and the kids he loved. Still, he added, “I think I’m the right guy for this job.”

In 2015, under Brubaker, Canada placed sixth at the women’s team finals at the World Gymnastics Championships in Glasgow. “People said it would never happen again,” Brubaker said. “Never say never.” At the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Team Canada’s Ellie Black finished fifth in the all-around category. It was the country’s best-ever showing by an individual gymnast. Brubaker told reporters he was already looking for athletes to compete in the 2020 and 2024 games.

He wouldn’t have the chance. In late 2017, based on reports made by Hunt and Spadafora, Sarnia police charged Brubaker with one count of invitation to sexual touching, three counts of sexual interference, three counts of sexual exploitation and three counts of sexual assault, dating back to a period between 2000 and 2007.

Shortly after Brubaker was arrested, he wrote an apology letter addressed to the complainants, as well as to his wife. In it, he stated: “I am guilty of crossing the line, but I want you all to know that my intentions were not sexual or premeditated.” (He later said the investigating officer pressured him to write the letter and told him what to write.)

Bluewater placed Brubaker on unpaid leave and banned him from the premises. GymCan followed suit, putting him on administrative leave pending the outcome of the criminal investigation. And yet Brubaker still had his supporters in Sarnia and the national gymnastics community. Elizabeth stuck by him, while continuing to train gymnasts at Bluewater.

Brubaker’s trial was scheduled for October of 2018 in a Sarnia courthouse. The judge, Deborah Austin, had 30 years behind the bench and a reputation for compassion and efficiency. By the start of the trial, the Crown had reduced the charges to one count each of sexual assault and sexual exploitation involving Hunt. Brubaker pleaded not guilty to both charges.

In the courtroom, Brubaker wore a suit jacket and tie, his short, greying hair styled into spikes. On the stand, Hunt described incidents that echoed Spadafora’s own experiences. She testified that from the time she was 12, Brubaker made her kiss him hello and goodbye on the lips. She also said that he would pick her up from school and take her to his house before practice, sometimes proposing that they take naps together, then spoon her in bed and tickle her belly. She alleged that he touched her inappropriately during massages.

In response, Brubaker’s defence team argued that Hunt was “bitter” she was not named to the Olympics team, unlike others he had trained. On the stand, Brubaker said Hunt had initiated the kissing out of “habit.” He added: “I don’t come from a kissy family, so to me it’s just part of the gymnast culture. It’s not something I need as a man.” He admitted that he had massaged Hunt, including touching her pubic area and around her breasts, but said it was only to improve her performance in the sport. As for the spooning and tickling, he said, “It never happened.”

The case against Brubaker began to fall apart mid-trial, when the Crown learned, then shared with the defence team and Justice Austin, that the investigating officer was in fact related by marriage to Hunt and had shared with her details of Brubaker’s interview with police. Brubaker’s defence lawyer, Patrick Ducharme, argued that the officer’s investigation lacked professional distance and that he had “cajoled a favourable statement out of her.” Justice Austin agreed and acquitted Brubaker. The Crown’s case, she wrote, was fatally compromised when the investigating officer abandoned both his oath of impartiality and his oath of secrecy. Austin stressed that none of her criticism of the officer should be taken as an indictment of the complainant: “She was forthright and appeared to be doing her best.” Her testimony, the judge said, was sincere and genuine.

With his case dismissed, Brubaker hugged his wife, and his supporters applauded. Ducharme told reporters that they would soon restore his client’s good name. The celebration was short-lived. Minutes after the judge read her decision, GymCan CEO Ian Moss stood outside the same Sarnia courthouse. He announced that during the trial, GymCan had received nearly a dozen written complaints about Dave and Elizabeth Brubaker from former Bluewater athletes, including Spadafora and Hunt, spanning from 1996 to 2017. The allegations were familiar: groping and fondling, pushing athletes to perform dangerous skills, belittling their weight and appearance, forcing them to train through injury. In response, GymCan was launching its own investigation. “We want to maintain the sanctity, the beauty of the sport,” Moss said. “We know we have work to do. Every sport has work to do.”

***

To investigate complaints against its own members, sports organizations like GymCan typically set up their own judicial systems. An internal investigation is meant to guarantee a fair process for the complainants and the accused, but it also helps protect GymCan from getting sued for erroneously dismissing or banning anyone.

Brubaker’s defence team argued that the complainant was “bitter” she wasn’t named to the Olympics team. Brubaker said she initiated the kissing out of “habit”: “It’s just part of gymnast culture. It’s not something I need as a man.”

To lead the investigation, GymCan hires an independent case manager who usually has a background in labour law, workplace investigations or human rights. The case manager weighs whether to refer the case to the authorities, to recommend a mediation process facilitated by GymCan or to begin their own investigation.

At the end of an internal investigation, the case manager presents a report and GymCan decides if a full disciplinary hearing is warranted. The case manager recommends the disciplinary panel members—usually two lawyers (one of which is named chair of the panel), and one sport or subject expert. Both GymCan and respondents like the Brubakers have a chance to either accept or reject the recommendations of the hearing panel. The closed procedure is at once a mock trial and an event that can destroy lives.

In September of 2020, more than a year after Brubaker was acquitted by the province, his GymCan hearing commenced. Similar to court proceedings on sexual assault and misconduct, GymCan’s process requires complainants to recount their allegations at the hearing—where the accused has a right to be present, and often is. And so the Brubakers, their lawyers, Moss, the three discipline panel members, GymCan’s lawyers and the case manager, plus 11 Bluewater gymnasts, all gathered over Zoom (the pandemic prevented them from meeting in person).

Spadafora spoke from a lawyer’s conference room in London, Ontario. The Brubakers’ counsel, civil litigation lawyer Tanya Pagliaroli, cross-examined her for over three hours. Spadafora remembers repeated questions about her hotel room in Taiwan. Next, Pagliaroli asked her about a photograph which showed her sitting on Dave’s lap in a pool, suggesting Spadafora wasn’t really on his lap at all but merely floating above it.

Spadafora found the experience traumatizing. Afterward, she had nightmares. “This is not a matter of a victim just explaining their story,” she says. “You have to prove this happened to you—time and time and time again, you have to prove it.” Spadafora and the other complainants told me how the hearing was the first time most of them learned about the extent of the Brubakers’ abuse. Hunt was deeply disturbed by how close her fellow gymnasts’ experiences matched her own.

Melanie Hunt testified that the Brubakers’ harsh methods gave her an eating disorder and that Dave touched her inappropriately. Here, she’s shown practising at ages nine (top left) and five (right), and at age 16 (bottom), sharing a hotel room with Dave during a competition in Ukraine.

During her testimony, she went into greater detail than she had at the trial, telling the disciplinary panel that, like Spadafora, she joined gymnastics as a young kid, at age four. Her parents wanted a safe place for her to do the kinds of things she was already doing, like flipping off swing sets. To Hunt, gymnastics was the closest she could get to flying. By age seven, she was part of the elite program, and the sport became her life. She convinced herself from an early age that the sport required a mindset of “no guts, no glory.” If she died attempting a cool gymnastics move, well, it would be an honourable death.

Hunt felt the harder she worked, the more likely she was to please Dave. The coach-athlete relationship became more toxic when she moved in with the Brubakers at age 12, a year after Spadafora. At the coaches’ home, milk and carbohydrates of any kind were forbidden. Thinking back to that time, she only remembers hunger. She developed a bingeing disorder and, after moving back home, quickly gained 10 pounds. She tried everything to lose weight, including taking diet pills and laxatives without her parents’ knowledge. Dave enrolled her in spin classes for extra exercise.

At 12, she says, the abuse turned sexual. First, Dave told her to kiss him in the morning when she arrived at the gym and in the evening when she left. He gave her massages and ran his fingers under her panty line. She recounted how he made her nap with him, putting his hand under her shirt and playing with her stomach. “I was living with Dave’s voice in my head and I didn’t know how to make a decision,” she told me. “I turned to him for everything.”

Imogen Paterson—shown at competitions at ages 12 (top) and eight (bottom right), and at age 14 at the Pacific Rim Championships in 2018 (bottom left)—says an uncomfortable encounter with Dave Brubaker, then in charge of Canada’s women’s national team, eventually led to her quitting the sport

One former gymnast who testified wasn’t a Bluewater athlete. In 2017, when she was 14, Imogen Paterson, who lived in Vancouver, desperately wanted to make the national team. That year, she had a chance to impress Dave Brubaker when they both attended an international competition in France. She remembers walking by him during warm-up, on her way to get some water, proudly wearing a Team Canada leotard she’d been given for the competition. When she was about 10 feet away from her coaches, Dave slapped her on the bum and remarked, “You look good in that suit.” She remembers the exact way he said “good,” the word drawn out, elastic. She forced herself to push it to the back of her mind so she could compete. Paterson told her mom what had happened on the ride home from the airport. With her Olympic dreams on the line, Paterson begged her mom not to make an issue of it. Three weeks later, after Dave was arrested, her mom told her coaches everything.

Paterson made the national team. But within a year, one of her coaches in B.C.—who Paterson says constantly demeaned, berated and gaslighted her—kicked her out of the gym, allegedly because Paterson’s parents were too demanding. Paterson found another gym and kept competing for Team Canada. Still, her experiences took a cumulative toll: shortly after testifying against Brubaker, Paterson realized gymnastics was destroying her mental and physical health. She let go of her Olympic dreams and quit the sport.

In March of 2021, after hearing testimony from Hunt, Spadafora, Paterson and eight other athletes, the discipline panel released its decision. It ruled in favour of the complainants. In total, the panel found 54 counts of misconduct and ethics code violations, including physical abuse, sexual harassment, child abuse and neglect, and discriminatory and unethical behaviour. “The Brubakers demonstrated a willful and persistent disregard for the ethical principles that governed their conduct and their obligations as coaches of child and young athletes,” the panel wrote. GymCan permanently banned Dave from gymnastics in Canada and suspended Elizabeth for five years. A year later, in April of 2022, having spent $300,000 in legal fees and believing the process was stacked against them, the Brubakers abruptly withdrew an appeal of the panel’s decision.

The Brubakers told me they were scapegoats—the first Canadian coaches to fall on the wrong side of #MeToo. They insist they never heard any accusations of mistreatment until Dave’s criminal trial. But how could 11 women get it wrong?

GymCan’s hearings and the reasoning behind its decisions aren’t public—sometimes not even to those directly involved. The Bluewater athletes I spoke to have GymCan’s final report on their case, but have collectively agreed not to share it as some athletes are not ready to have their stories heard.

The women who testified against their former coaches are now campaigning for greater changes in gymnastics. In response to the panel’s decision, they released a collective statement as the Bluewater Survivors. They commended the ban on Brubaker, but criticized the way GymCan handled their complaints. “It compounded the trauma of survivors and prolonged what had already been an open-ended nightmare,” they wrote in an open letter. “That process cannot be allowed to continue as is.”

***

Last October I interviewed the Brubakers, at first over email—while they wanted to ensure their voices were heard, and that the reporting was “balanced,” they were also nervous to meet with a journalist. Later, we spoke over the phone. Throughout our conversation they finished each other’s sentences, speaking warmly about their marriage and family and wistfully about their time as coaches. That demeanour shifted, however, when the conversation turned to the allegations against them, the GymCan investigation and Dave’s ban.

The Brubakers feel they are scapegoats—the first coaches to take the fall in GymCan’s quest to be on the right side of #MeToo, and the international backlash against gymnastics culture. To them, GymCan was forced into a difficult situation and acted with the intent of kicking the Brubakers out of the sport; they were never going to triumph at the hearing, let alone at an appeal. They insist that they had never heard any accusations of mistreatment until Dave’s criminal trial and are angry that GymCan seemed to suddenly change the rules on them after 40 years of coaching, during which they only received praise and success. They asked me, without really expecting an answer: if there are issues around the treatment of athletes, why was that treatment accepted for so long, only to change without GymCan communicating it to the coaches?

We talked about their coaching history and philosophy. In response to questions about the trial and the complainants’ experiences, the Brubakers were often evasive, explaining why they believe themselves to be the bigger victims. But if the allegations are false, I asked them, where did they come from? How could 11 women get it wrong? The Brubakers said they don’t know. In general, they tend to look away from the sexual misconduct allegations, preferring to frame the complaints as both historical and centred on alleged too-tough coaching. They say they love the sport and they want to help fix what they see as the “problem”—not an abusive culture, but rather a gap between how coaches do their jobs and how today’s athletes, who they consider overly sensitive, want them to do their jobs. “Gymnastics in Canada is being destroyed, and coaches are fleeing the country,” Dave said. “Coaches call us every week. They’re afraid. They’re saying, ‘If this can happen to the Brubakers, then it can happen to anyone.’ ”

***

Late last summer, I met Ian Moss and GymCan board chair Jeffrey Thomson over Zoom. Moss was at a cottage, and Thomson was in the middle of a long period of travelling, first to the U.K. for the Commonwealth Games and then to Turkey for the Islamic Games. Both men were eager for a chance to acknowledge GymCan isn’t perfect. “We know in gymnastics that we need to change. We all accept that. We’re not hiding behind some sort of rock,” said Moss. “We all believe that this sport cannot survive in a moribund state. It has to evolve.”

He added that national sport organizations like GymCan were traditionally set up to guide their sports on technical matters—how to reach the podium, how to excel, how to dominate—and that their staff usually don’t have expertise in dealing with abuse. Questions about whether, and how, organizations influence the outcome of complaints against their own members‚ the coaches, are fair, he allowed. He also pointed out that sports bodies have argued for years that it’s difficult for them to police themselves. That statement is true of any organization: everyone is biased toward their friends, their colleagues, themselves.

Thomson believes the criminal justice system failed the Bluewater athletes during Brubaker’s trial. He’s proud that GymCan did not let the couple go back to coaching without its own investigation. “It was a lot of money, a lot of time and a lot of resources to make sure that they never coached again. We went hard and it was not easy,” he said. “I can’t imagine what it must have been like for those girls and those women, but, you know, we got ’em in the end.”

To date, more than 100 athletes have signed onto a class action suit against Gymnastics Canada and several provincial federations, saying they contributed to their abuse by creating a toxic culture and failing to protect them

Last June, GymCan hired the consulting firm McLaren Global Sports Solutions to conduct a study of the organization’s culture. The firm will analyze GymCan’s safe sport policies, compile international findings of similar investigations across the world and interview athletes and members of the GymCan community. The company only takes on such work for a body like GymCan if the organization agrees to make the findings public.

The firm has completed investigations into abuse for several international and Canadian sports federations. Many gymnasts have said there’s no guarantee from McLaren that the process will avoid making them relive traumas—or that it’s meant to help them at all. After all, McLaren’s stated mission is to help its clients—in this case, GymCan—“protect and enhance their brand” and to “navigate difficult organizational issues.” It wasn’t hired to rewrite an entire sport’s culture. By the end of 2022, McLaren had collected hundreds of surveys and interviewed dozens of GymCan stakeholders, including a number of athletes who described being abused and wanted future kids to be protected.

For many gymnasts, the McLaren study is a half measure. Last spring, a former B.C. gymnast named Amelia Cline filed a class-action lawsuit against GymCan and several provincial gymnastics federations. The lawsuit states that the sport’s governing bodies contributed to the abuse of athletes by creating a toxic culture and failing to protect athletes in their care, many of whom were children. To date, more than 100 former athletes, including Spadafora and Hunt, have signed on to the lawsuit. Some of those athletes are pushing for a third-party investigation into both the sport and GymCan itself. An independent review, they argue, is the only way to ensure that, if needed, the harshest recommendations will be made: tear it all down, fire everybody, start over.

This past July, a possible saviour for gymnastics arrived in the form of a new federal office dedicated to sports integrity. Pascale St-Onge, the sports minister, modelled the commission on a similar body in the U.S., which was swamped with reports of abuse from the moment it was founded in 2017. In the 2022 federal budget, the government granted $16 million to the office over three years and appointed Sarah-Eve Pelletier, a lawyer and former national competitor in artistic swimming, as commissioner. The idea is for the office to operate as an independent, third-party investigator into any complaints received from athletes, parents or coaches.

The federal government isn’t giving sports organizations any choice but to change. In July, it suspended GymCan’s annual $2.9-million funding. The freeze was to last until GymCan became a signatory to the sports integrity office. If it signed on, GymCan would no longer receive abuse reports, investigate its own coaches or decide on disciplinary action; a case like the Brubaker one would be completely out of its hands. Sport organizations still have questions about how exactly the office will operate, how it will collect complaints, whether there will be a public database of sanctioned coaches and what support will be offered to athletes who complain of abuse.

Three national organizations initially signed on: Volleyball Canada, Weightlifting Canada and Hockey Canada. Then, in December, GymCan finally agreed to participate. It will still be responsible for keeping athletes safe, but it will no longer be the body that gets to decide how adequately it does that job.

***

It took a criminal trial and the Gymnastics Canada investigation, plus years of therapy, for Spadafora to fully confront what she had endured at Bluewater—that it wasn’t just tough coaching and inappropriate moments, but grooming and deep, constant abuse. Today, she feels closer to healing, and she’s also aware of how her experiences continue to affect her. She suffers from anxiety and panic attacks and was recently diagnosed with obsessive-

compulsive disorder.

In November, Spadafora met with eight former gymnasts for another round of testifying—this time in Ottawa, speaking at the Status of Women’s hearings on the safety of women and girls in sport. She’s joined dozens of other athletes organizing under Gymnasts for Change Canada. Together, they’re lobbying the government for a federal inquiry into Canadian sport. It can be exhausting to push for change, to share your deepest trauma, only to see the needle move the smallest bit. It can be frustrating to feel like too few care about the vulnerability of young athletes. But she’s determined to keep going. There’s too much at stake: the well-being of every athlete and the future of the sport she’s always loved, even when it didn’t love her back. She still believes it can change for the better. No kid should suffer abuse to taste victory.

This article appears in print in the February 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.