Inside the $24-million miniature Canada

In the Toronto underground, a patriotic visionary is building a model museum ten years in the making—and is just getting started

In real life, the Parliament building in Ottawa gets a light and fireworks show on Canada Day—but in Little Canada, it happens every fifteen minutes. (Photographs by Michael Kazimierczuk)

Share

In a basement in downtown Toronto, there’s a whole country. The new Little Canada miniature museum depicts Canada’s cities, small towns, mountains and waterfalls, all spectacularly alive with the magic of sound, animation and mechatronics. In one scene, the Maid of the Mist careens up a 16-foot Niagara River aglow with iridescent shades of pink, yellow and blue. In another, tiny skiers make their way down a hyper-realistic Mont-Sainte-Anne that overlooks an elaborate rendering of Old Quebec. It’s a patriotic passion project that took nearly a decade, $24 million from 218 investors, and dozens of artisans to create. And it’s one of the coolest things you’ll ever see.

Little Canada is meant to be educational, but verisimilitude is not its primary goal. The exhibits (which Little Canada calls destinations) are designed to evoke the real thing without being carbon copies; buildings within an area might be shuffled slightly to suit the display, for instance. The whole place is governed by a powerful sense of fun and whimsy, often spilling over into the fantastical. In Petit Quebec, a serpentine sea creature emerges from a construction site. A cross-section of the Château Laurier reveals rooms depicting scenes from novels and TV: James and the Giant Peach, the Schitt’s Creek motel room and the spooky dummies from Goosebumps, to name a few.

Chateau Frontenac, Quebec City: The hotel was contracted out to a company in Quebec. "It’s their building, and we didn’t want to potentially take away from any details they consider important," says design specialist Ailyah Tom. "It’s all 3D printed, and it came painted, but we added all the snow and lights. Applying the snow was a very long process because we wanted to simulate a natural look. Snow doesn’t just fall straight down; it’s blown around by wind and builds up in crevices or on rooftops. We use mostly spray paint, along with really tiny brushes for the details."

The destinations operate on what the staff call “miniature time,” a 15-minute day-to-night cycle represented with dramatic changes of light. Cars, fire trucks and boats glide on tracks powered by hidden magnets. Every 15 minutes, a Canada Day fireworks show illuminates mini-Parliament. In some scenes, the figurines move: tiny skiers shimmy down a bunny hill at Mont-Sainte-Anne.

It’s fitting that Little Canada is so whimsical, since the idea for the place came from a powerful hit of childhood nostalgia. One day in early 2011, Jean-Louis Brenninkmeijer, the attraction’s founder, was digging through boxes of his childhood things in the basement of his Oakville home. Brenninkmeijer, who emigrated from Brussels to Oakville in 1999, had recently quit a long career in his family’s business, which took him from retail to renewable energy to finance.

And that family business? It belongs to one of the wealthiest families in Europe. The Brenninkmeijers are a Dutch-German-Swiss dynasty with a considerable legacy and a net worth in the billions. The family’s centuries-old business interests include an international chain of clothing stores, a private-equity company, two banks and a real estate fund. But Jean-Louis wanted to do something different with his time. “I’m not a person who likes to sit behind a computer all day, look at figures and make reports,” he says. “I found it very tedious.”

ByWard Market, Ottawa: Moving vehicles are part of the scene in downtown Ottawa. "In the past few years, we’ve been able to implement technology that allows vehicles to move along a particular path using a hidden magnetic rail system," says mechatronics specialist Brad Parsons.

The boxes had been collecting dust for nearly a decade before his wife suggested he finally go through them. “They were full of my childhood model trains, some of which were passed on to me by my father,” he says. “The excitement suddenly came back. Every time I opened a box and unwrapped a locomotive or a piece of track, I thought, ‘Oh, I forgot about this one!’ I remember finding a particular train, a green three-piece locomotive nicknamed the Swiss Crocodile, which I associate with my father. I called him straight away, and he was quite chuckled by the fact that I had just unpacked it.”

Brenninkmeijer began to explore the idea of building a model train layout at home. He ordered two tables, laid down some track and got to work reigniting a boyhood passion that had long been tucked away, just like his old boxes. In 2011, he visited a museum in Hamburg called Miniature Wonderland, which recreates pockets of Europe in exquisite detail. That visit, coupled with his newly revived model train hobby, sparked a daydream about creating something similar in Canada. “At first I thought, That’s ridiculous. I don’t have the skills to do something like that,” he says. “But I couldn’t stop thinking about it.”

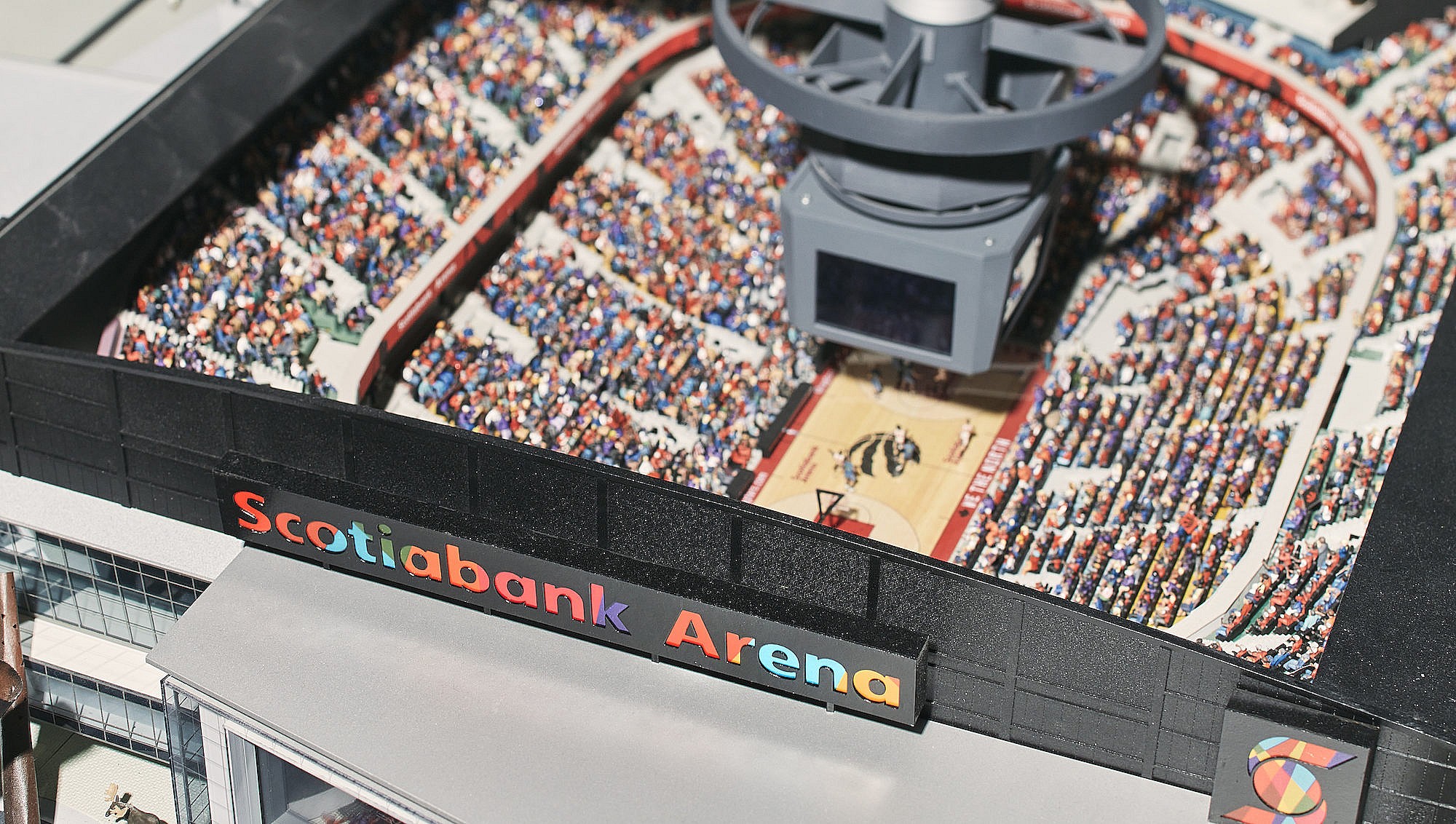

Scotiabank Arena, Toronto: The screen on the inside plays footage from 2019 Toronto Raptors NBA title-clinching game against the Golden State Warriors. "You can’t see him in this shot, but Maurice the red Moose, Little Canada’s mascot, is hidden in this destination," says design specialist Aliyah Tom. "We move him around every couple of weeks as a treasure hunt for the kids."

Tentatively, Brenninkmeijer reached out to a few local model train clubs to see if anyone wanted to get on board. Dave MacLean, a civil engineer and president of the Model Railroad Club of Toronto, responded right away. It took one lunch for the two to become partners on the project, and in their early conversations, the idea evolved from a model train exhibit to a miniature world that would depict Canada coast to coast, incorporating trains throughout parts of the build.

For Brenninkmeijer, the idea came from his love for Canada. He had initially moved to Oakville temporarily for work, but liked it so much he decided to stay. “I fell in love with the country right away,” he says. “For me, it was the seasons, the friendly people and the diversity of terrain. You have everything: mountains and deserts and lakes and forests.”

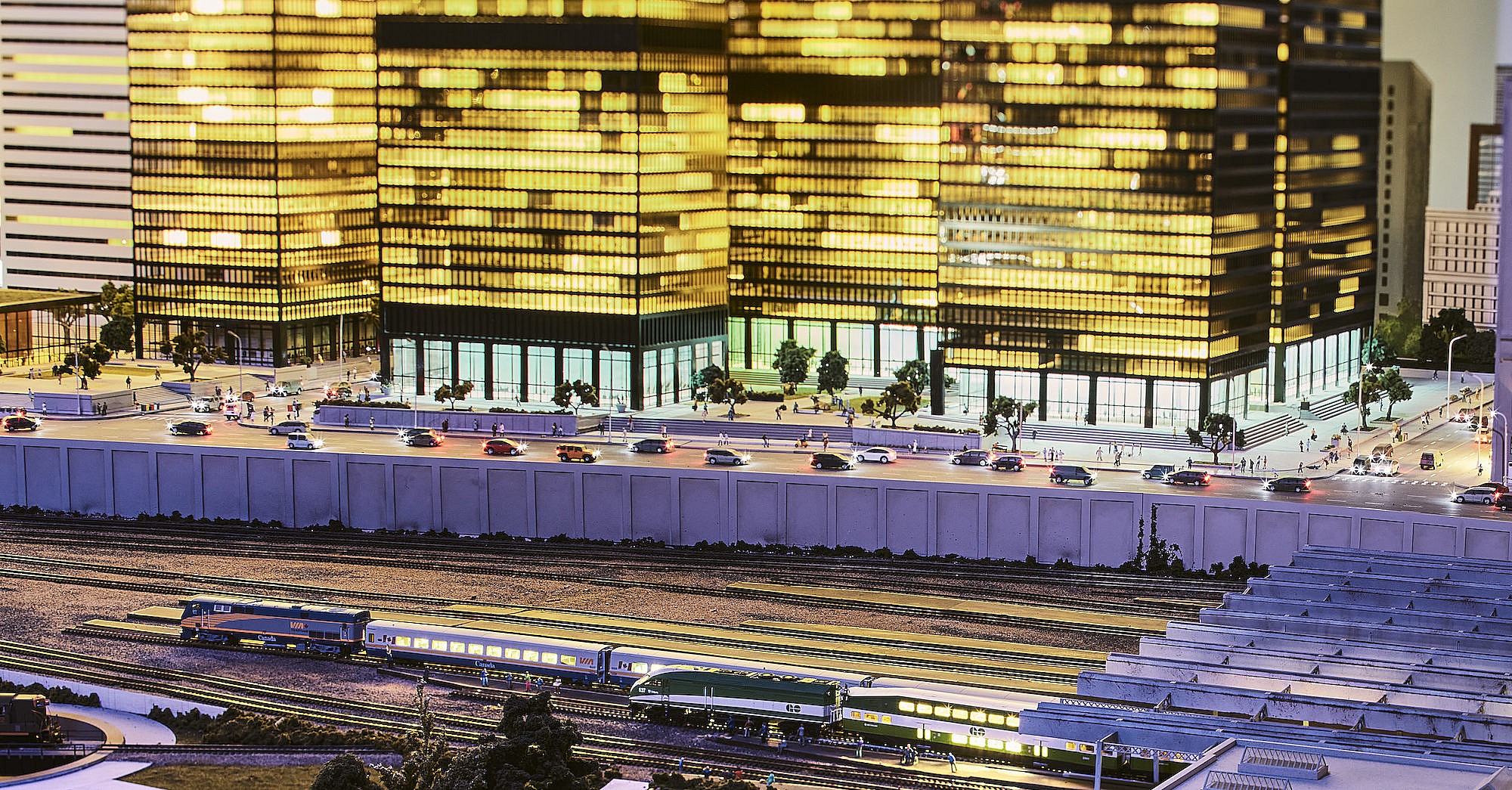

Union Station, Toronto: "Placing miniature people in front of the Union Station took a couple of days, part of which was spent fixing people as their ankles broke from the process, which happens more often than you’d think," says visual arts specialist Damien Webb. "The cars move, so they are all individually wired; when we placed the vehicles, we had to drill holes into the road to connect the wires to a ribbon cable, which is painstaking work."

In 2013, Brenninkmeijer and MacLean signed the lease on a 5,000-square-foot warehouse space in Mississauga, Ontario. With a team of 10 makers—including hobbyists from the model railroad club—the pair built models of Toronto and the Golden Horseshoe, the first two destinations. They financed it themselves, with investments from friends and family. Between 2014 and 2018, after securing further investments, the team swelled to 30 makers and developed three more destinations: Niagara, Ottawa and Quebec.

Brenninkmeijer and MacLean scouted dozens of locations before finally signing a lease at 10 Dundas, a 45,000-square-foot space smack-dab in downtown Toronto, in August of 2019. The plan was to open the following July with five destinations, plus one under construction, but the pandemic delayed their plans for a year. “Opening day itself was very disappointing,” Brenninkmeijer admits. “We didn’t have as many visitors as I had hoped. But the next weekend was great, and it grew from there.”

Niagara-On-The-Lake: "We worked with Niagara on the Lake’s tourism board to determine which structures we should represent in the neighbourhood, says structure and stories leader Anita Fenton. "An important one was the Memorial Clock Tower, which was built to memorialize town residents who served in the First World War. It’s made from sheets of styrene, a softer plastic that can be cut by hand."

In the next three years, Little Canada is set to unveil the East Coast, the Prairies and the North. By 2028, it hopes to open the Rockies, the West Coast and Montreal. The Little North was supposed to be under construction at the time of opening, but it’s been delayed till 2025 in an effort to find the appropriate artisans for the job. “We want it to be designed and built by an Indigenous team,” says Brenninkmeijer.

Today, the team consists of 50 builders, including hobbyist dollhouse makers, visual artists, industrial designers, electrical engineers and mechatronics specialists. A single destination can take anywhere between 40 to 600 work-hours to complete, depending on its size and complexity. Most of the detail—and thus most of the work—goes into what the artisans call the “A-level,” or the highly visible stretch from the edge of a piece to two feet back. In the early days of Little Canada, the makers relied primarily on “kit-bashing”—creatively repurposing and customizing bits and pieces from pre-existing model kits. Now, much of the work is done from scratch with customized 3-D-printed materials and intricately designed electrical work that brings it all to life.

On most days, you can find Brenninkmeijer wandering the halls of Little Canada, basking in his new life, worlds away from the paper-pushing career he once dreaded. “I’m a people person. I like being on the floor, walking around and talking to guests,” he says. “Every 15 minutes, there’s a Canada Day celebration in Little Ottawa at the Parliament building. We’ve seen people tear up, clap as a group. Last weekend, we had a group of young kids standing on the railing and singing along to O Canada. I had goosebumps.”

This article appears in print in the July 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here, or buy the issue online here.