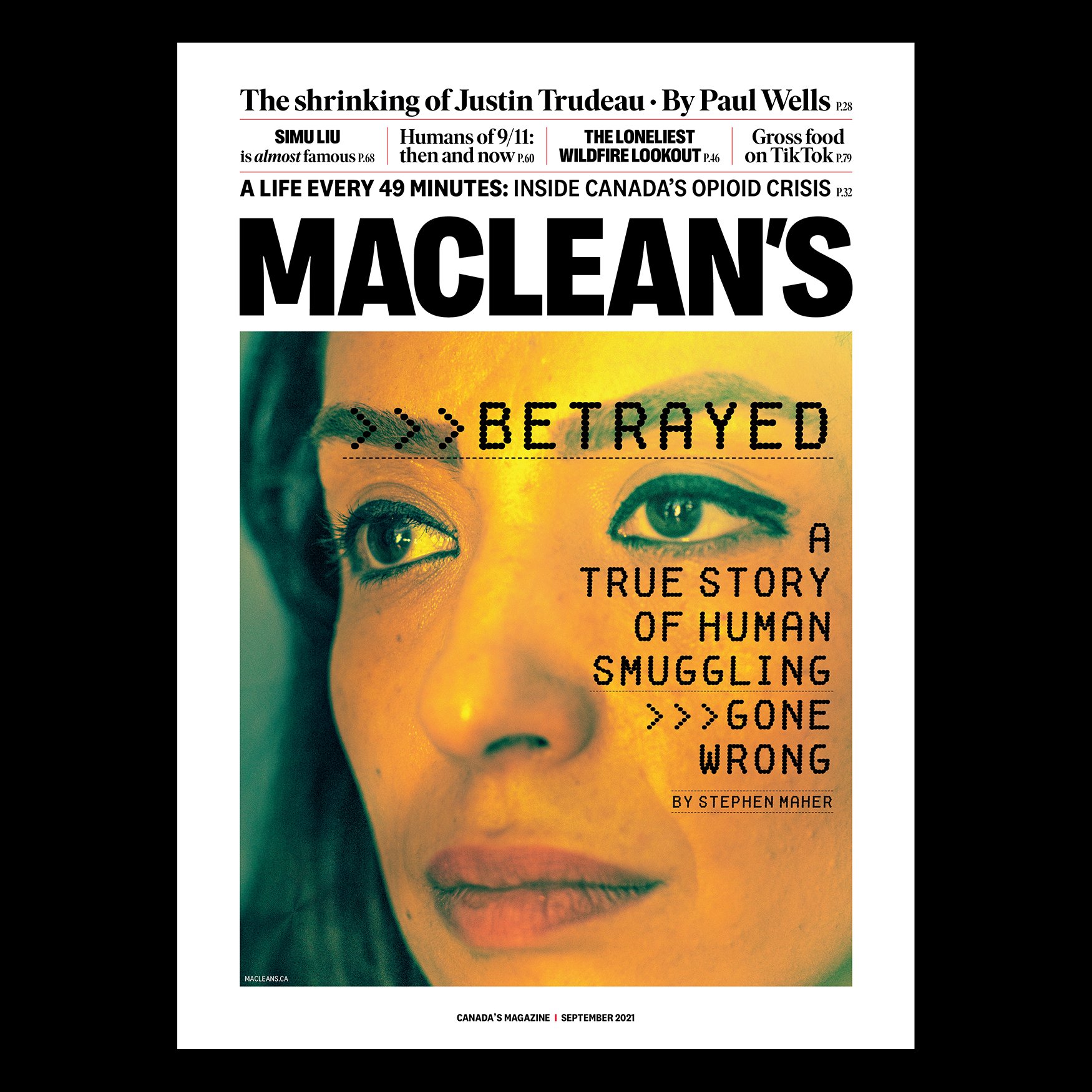

Escape from Iran

Fake passports, river crossings and big money: Mahnaz Alizadeh’s desperate struggle to find refuge in Canada

Mahnaz Alizadeh

Share

The plan to get to Canada was ingenious, complex and terrifying.

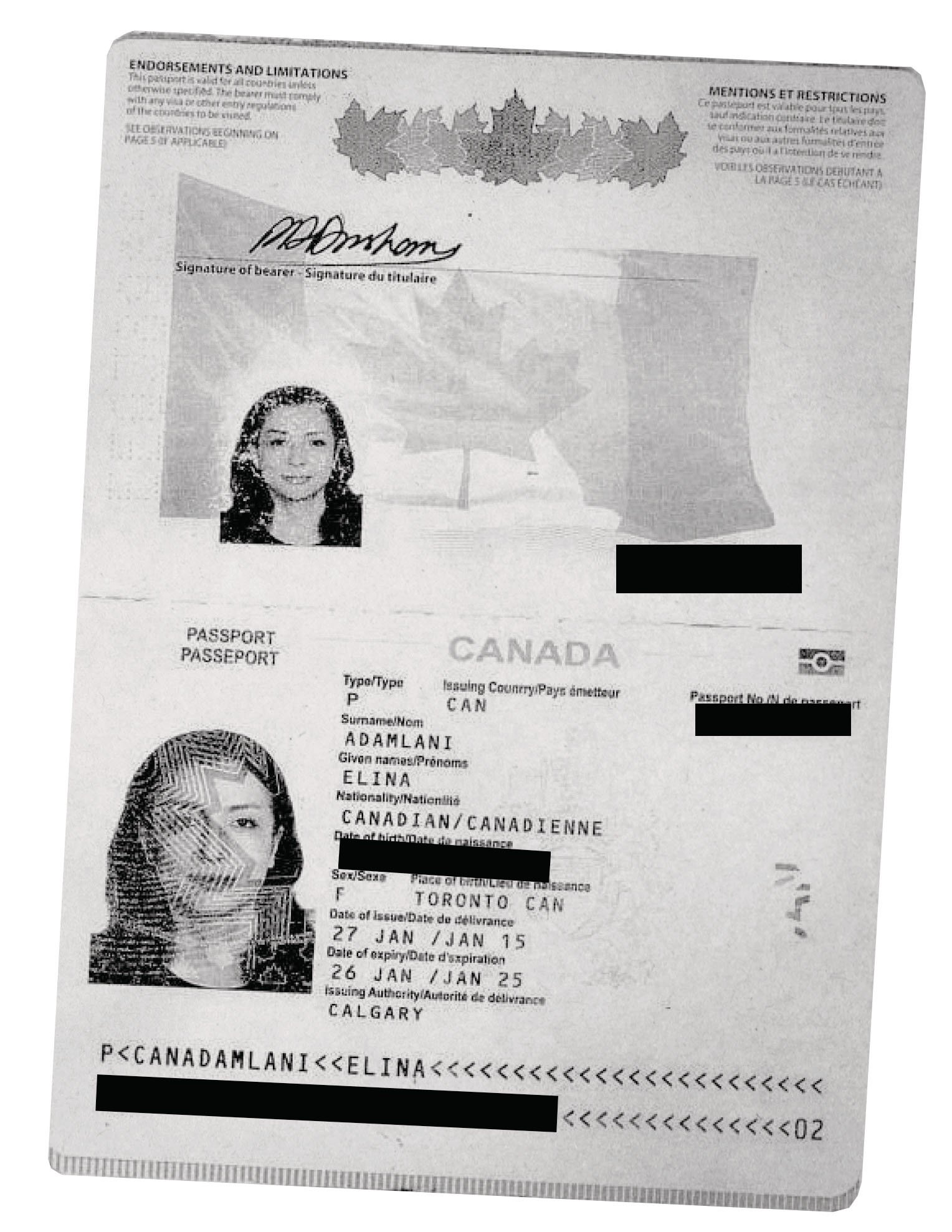

Mahnaz Alizadeh was supposed to board a flight to Panama from Ecuador using her real Iranian passport. She was to carry a forged boarding pass that showed she was ultimately headed home to Tehran. Once she had shown that to gain entry to the international departures area of the Tocumen International Airport in Panama City, she was to discard it and take out a boarding pass for a flight to Toronto and a doctored Canadian passport, both under the same alias—Elina Adamlani.

The passport, which she was told was made for her in Turkey, was likely good enough to pass only a cursory examination. Pages had been doctored: the passport numbers on two different pages didn’t match, the margin of one page was too small, and biometric data had been printed with an inkjet printer, not using offset printing. If a customs agent passed it under ultraviolet light, it would be immediately flagged as fake; the multicoloured pattern—with the maple leaf and Canada’s coat of arms—that shows up under UV light was missing.

Once at Toronto’s Pearson airport, she was to tear up the fake passport and flush it down the toilet.

“You’re supposed to wait, not to go to the passport check until it is clear of passengers. And just go there later . . . and you say that you just arrived there and you don’t have a passport and you’re seeking asylum,” she says, explaining the plan.

She never made it that far.

Mousavi’s defeat in Iran’s 2009 presidential election spurred mass protests by those who believed Ahmadinejad had stolen the election (Olivier Laban-Mattei/AFP/Getty Images)

***

In a way, Alizadeh’s journey to Canada began when she was 24. She is now 35. In her early 20s, she was in the last year of film school, living with her parents in Tehran, crazy for cinema—an admirer of Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan and Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski. She especially admired Three Colors: Blue, Kieślowski’s masterful portrait of grief and isolation.

She wanted to make documentaries “to depict the problems and the sufferings in [Iran],” and did a lot of work on a student film about street children in Tehran.

When reformer Mir-Hossein Mousavi ran against hardline president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, many Iranians hoped the government might finally change. Hopes were dashed when Ahmadinejad appeared to steal the election, drawing thousands of Iranians into the streets in the largest popular revolt against their country’s hardline fundamentalist government since the revolution in 1979. For a time it looked like it might succeed, but the Intelligence and Public Security Police won the day. They rounded up thousands of protesters: among them, Alizadeh.

She had returned to her parents’ home late after attending a screening at a film festival. She had just changed into her pyjamas and was getting ready for bed when there was a hard knock on the door. There were secret police outside, large men in plain clothes, with guns. They took her in her pyjamas to Evin Prison.

Evin is a sprawling concrete complex on the outskirts of Tehran. It was built in 1972 by Iran’s last shah to lock up political prisoners. Human rights groups say rape, torture and the execution of political prisoners are common there. In 2003, Zahra Kazemi, an Iranian-Canadian photographer, was arrested outside Evin for taking pictures of a demonstration by friends and relatives of disappeared protesters who were believed to be inside. Eighteen days later, she was dead. The government blamed a stroke, but was later forced to admit she had been beaten to death.

Alizadeh knew the stories; she was ready for the 16-hour interrogations, full of abusive insults, when they arrived. When they took her to the interrogation room, she was made to wear a blindfold encrusted with blood. Once, they took her to a basement room where she could smell blood and hear the cries of torture victims.

She spent three weeks in Evin for “acting against the national security of the Islamic republic.” After her release, Alizadeh kept returning to the protests; prison had entrenched her activism. Although she was careful to leave her cameras at home and turn her phone off to avoid detection, she couldn’t stay away.

She continued going to protests even after her friend, Sane Jaleh, was killed at one by government security forces. “I was very happy to be present at the protests after my imprisonment,” she says.

For three years she worked on a secret, dangerous project, filming Nasrin Sotoudeh, a famously courageous Iranian human rights lawyer who represented religious minorities, political prisoners and feminist activists, including women who were arrested for protesting for the right to go bare-headed. Those women had stood in parks, waving their headscarves in the air, taking selfies, daring the police to arrest them.

Alizadeh’s footage of Sotoudeh was used in last year’s widely praised documentary, Nasrin. The film was put together by Americans using footage shot in Iran by Alizadeh and others. Working on the film was so dangerous that Alizadeh and other Iranian crew members’ names could not appear in the credits, although the director has confirmed her involvement. Sotoudeh was arrested in 2019, while the film was in production, and sentenced to decades in prison and 148 lashes.

Alizadeh decided then that she had to get out of Iran.

“Some of my colleagues and friends were arrested and all of them were being questioned about me,” she says in a recent interview.

Several times she got phone calls from strangers offering her jobs, asking her to show up for an interview and saying a friend recommended her. But when she called the friend directly, they would be perplexed. It was a trap, she insists, designed to track her down and interrogate her further.

Alizadeh was at even greater risk because she was in a secret relationship with a woman, which according to Iran’s legal code is punishable by imprisonment, 100 lashes or even execution. She feared for her safety, but also exposure, which could damage her friendships and family life. Even in progressive circles, being gay in Iran is taboo. “If it was discovered, aside from the criminal aspect of it, the very fact that everybody, including my family, would know about it would be quite frightening.”

She was under “unbearable stress.” She decided to end her relationship with the woman she loved—and still loves—and leave the country for good.

An old Iranian-Canadian friend came to the rescue. He suggested someone he knew could help get her into Canada by first getting a tourist visa; she could apply for refugee status once in the country.

Alizadeh saw in Canada a refuge at last. Instead, she landed in a hell that she could never have imagined—worse, even, than Evin.

***

Canada rejected Alizadeh’s application for a tourist visa, so Plan A was out. Plan B, her contact told her, was to fly to Ecuador, where he had connections, and get a visa. At this point, she had no reason to doubt the legitimacy of that plan, or to imagine there would eventually be a Plan C—the one with the obviously fake passport in a name that wasn’t hers.

She sold her car, cameras and computer, and borrowed money from her parents so she could pay a US$5,000 deposit, half of the required total, to an intermediary. On Oct. 30, 2019, she signed a contract with an Iranian Canadian who lived in Vancouver named Reza Sahami, who she says offered to help with the travel plans. The document, written in Farsi, is titled “Canadian immigration agreement.” In it, Alizadeh “is committed to pay an amount of 10,000 USD to the first party [Sahami] which this amount includes all expenditures. The duration of the work is approximately one month.” Sahami acknowledges the contract with Alizadeh, though says he was merely a middleman helping to facilitate her travels.

Alizadeh described what followed over several hours of interviews through a Farsi translator. Maclean’s also interviewed more than a dozen people over four continents to corroborate her story, including lawyers, a former work associate, activists and people she met along the way. We reviewed hundreds of pages of court documents related to her case.

On Jan. 8, 2020, Alizadeh flew out of Tehran with one carry-on item and one checked bag. She was leaving forever and wanted to bring more of her belongings, but she says her contact told her that too much luggage could attract unwanted attention.

Alizadeh was nervous. She wasn’t sure the Iranian government would let her go, and it was a time of tense conflict between the increasingly hardline regime and the Trump administration. The previous week, Donald Trump had ordered the assassination by drone of Qasem Soleimani, an Iranian military commander the Americans considered a terrorist. On the morning of Alizadeh’s flight, the Iranians ordered retaliatory missile strikes targeting American bases throughout Iraq, injuring U.S. soldiers.

And while Alizadeh was getting ready to travel, Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, a Boeing 737-800 with 176 people aboard, including 57 Canadians, was shot down by Iranian anti-aircraft missiles minutes after it took off on its way to Kyiv.

“The airport was deserted, and it was as if the smell of death was coming from all over the airport,” she says. “I felt like it was my funeral.”

She checked into an airport hotel, desperate with worry. It was becoming clear that she was in the grips of a human smuggling operation.

Alizadeh’s flight took off 16 hours after the Ukrainian jet was shot down. She flew to Qatar, then to São Paulo, Brazil, and on to Quito, Ecuador, following instructions from her contact. Neither Qatar nor Ecuador then required a visa, although both subsequently tightened their rules.

Alizadeh, who speaks some basic English and no Spanish, checked into an airport hotel in Quito and waited for further instructions, desperate with worry. When she finally heard from someone, after three days, she says he told her she had to pay the balance of the fee, even though she understood it was to be paid once she arrived in Canada. Otherwise, she would have to wait in Quito.

It was becoming clear that she was in the grips of a human smuggling operation.

Sahami, with whom she had signed the contract, acknowledges accepting money from Alizadeh but says he was passing it on to those who were in fact involved in her travels. “She gave me the money and made the contract with me,” he says in an interview. “So I pay when she gets a visa. I paid them, a travel agency, the money. That’s what the contract is about.” Sahami says he had nothing to do with smuggling or immigration. He has never been convicted of any immigration-related offences.

Stranded, isolated and afraid to go outside the hotel, Alizadeh asked her family to pay the remaining fee.

After her parents arranged for transfer of the funds, Alizadeh was picked up in a vehicle and taken to a hostel in Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city. She says there were more than a dozen other Iranians waiting there, all Canada-bound. She remains chilled by the memory of walking with one of the smugglers on the street in the rough-and-tumble port town, where he would be warmly greeted by men she found terrifying. “I have never been so far from the country of my friends and family,” she says.

Alizadeh was furious when the smugglers revealed that the plan to get her to Canada had changed. After they had her money, it was revealed that there would be no tourist visa, she says. Instead, there was a fake passport.

It struck her that Plan C, in which she would fly from Ecuador to Panama with her real passport, then on to Toronto using the fake one, was the only plan the smugglers had in mind all along.

Alizadeh was upset, fearing she’d be implicated in an illegal scheme. She flatly refused, afraid her anxiety would betray her and that she would be easily arrested and jailed.

“[One of the smugglers] kept telling me, ‘I’ve been doing this for almost 30 years, 26 years,’ ” she says. “ ‘I’ve taken all my family members there. I’ve taken so many other people there. You’re just making too much fuss.’ ” She says she convinced him, though, that she couldn’t manage the stress of flying with a fake passport. They agreed he would put her through an airport where he had connections, so that she could be reassured, and started making alternative plans.

Alizadeh says she doesn’t believe any of the roughly 20 people she got to know while travelling for over seven months in South America were actually refugees, although they all planned to claim refugee status in Canada. They were, she says, just well-off Iranians who could afford the price to get to the country’s doorstep.

***

There is no official data for tracking how many people are smuggled into Canada every year, but likely many thousands—at least until COVID-19 shut borders everywhere, stranding migrants in transit. Since 2017, about 20,000 so-called “irregular” migrants a year have been crossing into Canada through the land border, mostly at Roxham Road in Quebec. Others, such as the group Alizadeh was travelling with, attempt to enter through airports with tourist visas. In 2019, before COVID, 64,040 people applied for asylum in Canada. It is likely many of them had employed a smuggler to help them get here.

Unlike its U.S. counterpart, the Canadian government is reluctant to make estimates, says McGill law professor François Crépeau, who was the special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants for the United Nations from 2011 to 2017. “But the figures I hear are between 500,000 and 750,000,” Crépeau says.

Many asylum seekers and undocumented workers have used the services of a human smuggler, according to academic research in other countries.

It is a lucrative business. Alizadeh got a special deal because she had a friend in common with the smugglers. While her contract said US$10,000, she was told US$30,000 was the going rate.

That’s in the same ballpark as the fee paid by a group of Sri Lankan Tamils, some Canada-bound, who ended up in detention in Turks and Caicos. They entered that country illegally in 2019 on a crowded sailboat from Haiti, according to Tim Prudhoe, a lawyer representing the migrants. Prudhoe took on the case pro bono and was successful in arguing a case to have them released.

There were 30 migrants involved in that case and each would have paid upwards of US$20,000. “That’s a serious amount of coin,” says Prudhoe.

The smuggler in this case, Sri Kajamukam Chelliah, a Sri Lankan Canadian, stood to receive an estimated $1 million from his passengers. He was sentenced to 32 months in a U.S. prison in May.

Smugglers like Chelliah move people from countries with weak or corrupt governments, like Haiti or Peru, because there is little chance of getting caught there. And they like to send them to Canada, Prudhoe says, where the consequences, if caught, are much less severe than in the U.S.

Smuggling is a massive global business. Three years ago, the UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime estimated it to be a $6 billion-a-year industry and migrants pay the price, both financially and in suffering. An unknown number die every year—drowning in the Mediterranean en route to Italy, dying of thirst in the Sonoran Desert on the way to Arizona or being murdered trying to cross the Darien Gap into Panama. Others are sexually assaulted, cheated of their money or extorted.

“The families pay them and then sometimes these smugglers, who are not as organized as people think, just say we need more money or you’re never going to see your family member again,” says an official with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, speaking off the record because they were not authorized to comment. “Or, we will take them to this location but we need more money if you want us to take them to the next country.”

Which is how Alizadeh found herself in Peru.

***

In 2020, the smuggling ring that Alizadeh found herself in was running into problems. Several of the clients were arrested in transit while Alizadeh was waiting in Ecuador. Then the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, stranding migrants around the world.

At the end of February, almost two months after Alizadeh arrived in South America, the plan to get her to Canada changed yet again. The leader of the smuggling ring decided Alizadeh and her cohort would be better off trying their luck in Peru.

Alizadeh and an Iranian family crossed into Peru from the Ecuadorian border town of Huaquillas without going through passport control. Alizadeh says she didn’t know she had crossed an unmarked border until later.

By this time, Peru had been hard hit by COVID-19; strict quarantine rules meant Alizadeh was stuck indoors. “I stayed for six months, and every week I waited for the borders to open, and every week the quarantine was extended, and the wait was terrible,” she says. “The fear that if I got sick I would . . . die alone in exile.” The fear of death “accompanied me from the beginning.”

Alizadeh asked for help from Pastor John Lennon, an American minister she had met at a church in Quito who ministers to victims of human smuggling, providing them with food while they are stranded. Alizadeh sent the pastor despairing texts after she moved to Peru, complaining of her plight and describing the smuggler she was travelling with as a cheat who was exploiting her.

Seven months after leaving Iran, on Aug. 28, 2020, Alizadeh and six other Iranians crossed into Brazil on foot at the village of Assis, deep in the jungle, wading across a shallow river.

But a taxi driver they hired to move their luggage started talking to the border police, who became curious. Some of the Iranians panicked and the police arrested them all, caught in possession of doctored passports from Israel, Denmark and Canada. According to court documents, the passports had all been reported as stolen.

For Alizadeh, it was the next chapter of a terrible ordeal. The Brazilians transferred the Iranians in handcuffs to the Francisco d’Oliveira Conde Prison Complex in Rio Branco, an eight-hour drive from the Peruvian border.

At first, Alizadeh was in solitary confinement. Colourful jungle birds would fly in and out of her cell. “I talked to them and I felt they could listen to me,” Alizadeh says. “I was alone in my cell for the first few days, crying night until morning and pressing my teeth together so hard that I realized that one of my teeth had broken due to high pressure.”

Police started the laborious work of going through the phones of the migrants, which contained copies of fake travel documents, text messages in English, Farsi and Spanish, and wire transfers. They erroneously concluded she was one of the smugglers. Documents filed in court by the Brazilian police show that they believed Alizadeh was “participating not as a victim, but as a co-author or participant.”

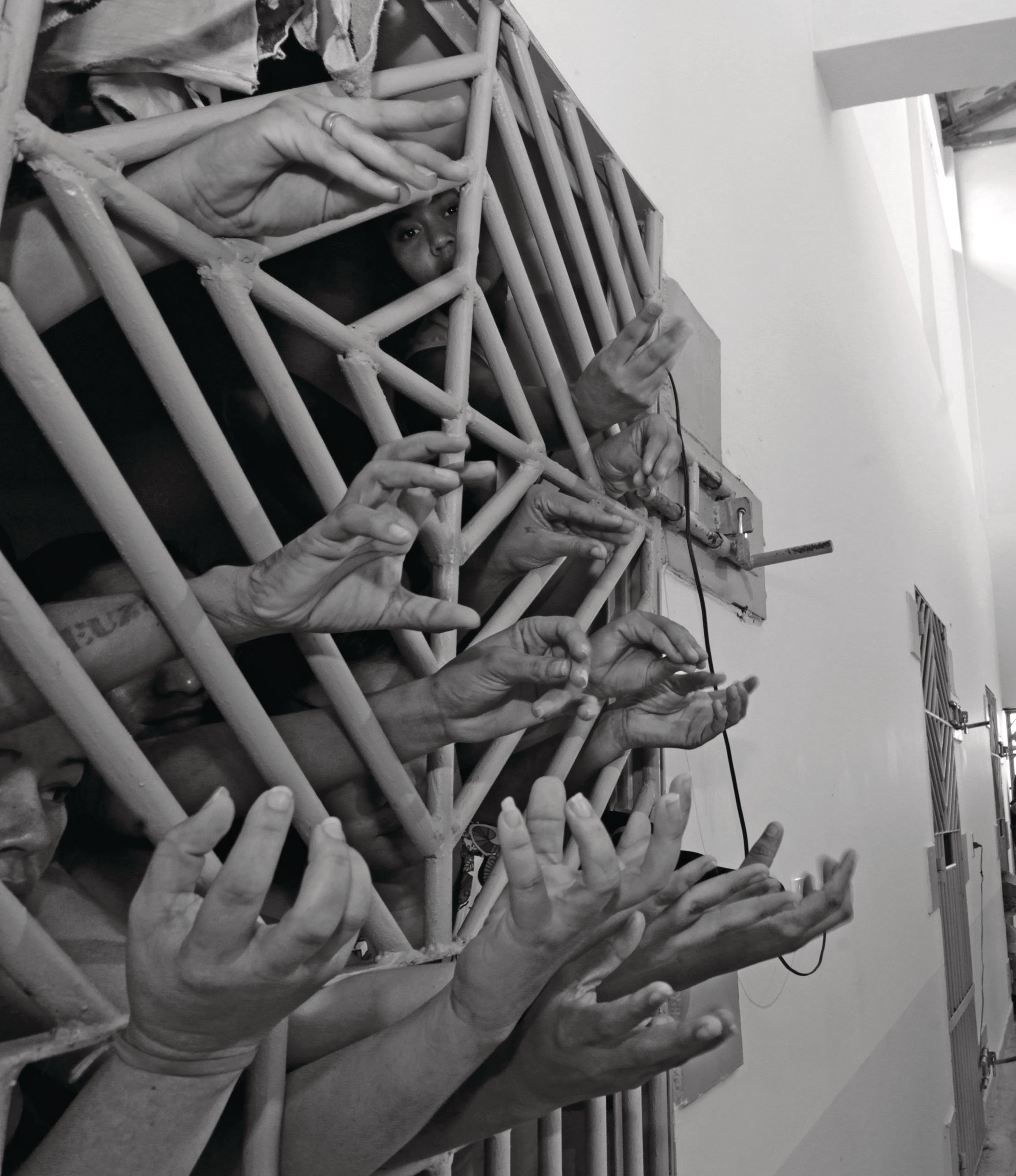

The women’s facility at the Rio Branco complex has a capacity for 96 inmates but had almost three times as many at the time (Courtesy of Luiz Silveira/Agência CNJ)

***

The women’s facility at the Rio Branco prison complex is overcrowded, unsanitary, infested by mosquitoes and cockroaches, and so dominated by two rival gangs that the prison managers keep inmates associated with them in separate wings, asking their gang affiliation when they arrive.

The prison has a capacity for 96 inmates but had almost three times as many around the time Alizadeh was there, according to a Brazilian media report. There were about 20 in Alizadeh’s cell.

At first she slept on the floor, sharing a blanket with another inmate. Water was turned on twice a day for short periods. There was no privacy in the bathroom. Inmates were not provided with sanitary supplies, which meant “prisoners use crumbs of bread and pieces of cloth to contain menstruation, as tampons only arrive through donation,” according to a report from Brazil’s Folhapress newspaper.

The other prisoners were mostly accused drug traffickers, and although they were kind to Alizadeh, there was often the threat of violence in the air. “One of the prisoners bragged basically about how she had killed a [rival gang member] and took her heart out of her chest.”

Alizadeh was once caught between fighting gangs, and pepper-sprayed along with the combatants. The other prisoners helped her rinse her eyes. Mostly she just sat, alone, unable to communicate, trying to keep to herself. She often had panic attacks.

“One day a new Brazilian inmate came, and they decided to put her in my cell because she knew some English. The whole prison started to clap knowing that I could finally communicate with someone.”

Eventually, Alizadeh’s plight came to the attention of Solene Oliveira da Costa, a prison ombudsman Alizadeh describes as her “angel.” “Seeing this woman in handcuffs, without speaking Portuguese and crying copiously, made me cry, too,” Costa told Fabiano Maisonnave, a Brazilian journalist who wrote about the case.

Alizadeh was released on bail on Oct. 16, 2020. She had spent 49 days in prison. Maisonnave published a story about her, which got the attention of Brazilian activists. Human rights lawyers took up her cause. Friends helped organize a campaign. Contacts from the international film industry who knew about her work on the Nasrin documentary sent letters of support. With a team behind her, she gradually came to believe her ordeal might end.

***

A week after Alizadeh was captured at the border, Reza Sahami, who was also in Brazil, was arrested by the federal police and charged with smuggling and falsifying official documents. Sahami says he wasn’t with the Iranians, but that he was at the border to help them, like a good Samaritan.

Just days earlier, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s attaché for Brazil, Robert Fuentes, sent a letter to the Brazilian police with information about Sahami’s background. ICE records show that he had been investigated—but not charged or convicted—in 2009 for suspected human smuggling involving the movement of Iranians through the Dominican Republic, in 2010 for a scheme to acquire stolen Iranian passports in Thailand, and in 2013 for smuggling Iranian and Afghan migrants through Venezuela and Mexico.

According to court documents in Brazil, on March 4, 2020, Sahami and six Iranians with fake passports had been arrested by Peruvian police trying to board an internal flight. Sahami was charged with bribery for offering money to a customs official. (He says this is not true. “I saw some Persian people at the airport had some problems with their entry to Peru. So I translated for them and that was—it was no problem.”)

‘I was alone in my cell for the first few days, crying night until morning and pressing my teeth together so hard that I realized that one had broken’

After his arrest in Brazil, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement issued a news release with the headline “ICE, Brazil Federal Police arrest alleged leader of major human smuggling organization.”

“Sahami has been smuggling criminals across international borders for over 10 years,” Fuentes says in the release. “We are grateful to our Brazilian partners for the unwavering efforts not only in this investigation, but in our overall strong partnership in combating transnational criminal organizations.”

Sahami was released on bail the same day as Alizadeh.

In two lengthy interviews, Sahami denied having anything to do with immigration work or smuggling. He says that he makes his living from a construction business and renting apartments in Iran.

He says in an email that he faced “a serious accusation in September 2020 in Peru and Brazil border by Brazilian border security and with no evidence I was detained for 45 days and I was released with no explanation and no apology from Brazilian government. This incident impacted my life on the hardest level for one year.”

In one interview, he says that prison wasn’t so bad for him.

“Even that time I was relaxed,” he says. “I didn’t have stress. No. As soon as I arrived there, I found so many good friends inside there and they take care of me. I lived like a king there and I came out. No problem. I wasn’t raped. I wasn’t killed, I wasn’t assaulted. I was fine for the whole time. That’s who I am. Any situation, I can deal with. Wherever I go, whatever the situation I have, I’m calm.”

Sahami’s assertions that he has nothing to do with immigration do not appear to be consistent with court documents in Brazil or with the accounts of three witnesses who say they had dealings with Sahami in South America—two of whom were trying to get to Canada, and one who works with migrants. And the name of Sahami’s Instagram account—which was shut down after Maclean’s contacted him—suggests he was involved in the business: @rezaimmigration2018.

Sahami points to his eventual release as proof that all the evidence against him was nonsense. “Think about it,” he says with a laugh. “If they know I’m the biggest smuggler and they can’t do anything, what does it suggest to you? Either I am not, or they don’t know s–t. Which one?”

On Nov. 5, 2020, Marc Antoine Fortin, an RCMP liaison officer in Bogotá, Colombia, wrote to the Brazilian police asking for Sahami’s passport back. “This request is because the passport is owned by the Government of Canada and not its holder,” Fortin wrote. “Furthermore, as part of the [Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada] review, and for Canada’s interest in the case of Sahami, we respectfully request to share with us copies of the prison and the search and seizure warrants issued in relation to this case in Brazil.”

The letter also says “analyses are being carried out in Canada.”

Brazilian court records show Sahami flew from São Paulo to Istanbul on Dec. 25, 2020, using his Iranian passport, without having collected his Canadian passport. Neither ICE, the RCMP nor Brazilian police will comment on why Sahami was able to leave Brazil. The RCMP says it can’t talk about what happened. “There is an ongoing investigation related to some elements mentioned in the question,” Cpl. Kim Chamberland says in a recent email. “Therefore, RCMP can not provide more specific information at this time.”

Another possible explanation for his release, of course, is that he is innocent.

Sahami says he has since returned to Vancouver.

As of late July, the charges against Sahami were still pending in Brazil. Prosecutors, meanwhile, have recommended that the smuggling charges against Alizadeh be dropped. She still faces a charge of using a fake passport.

***

Experts say smugglers are able to profit from people like Alizadeh because of the rules our government has established. “The reason that smugglers exist is because countries like Canada put up barriers to prevent people who need to escape danger, and so the people needing to escape danger turn to smugglers in order to get to somewhere safe,” says Janet Dench, executive director of the Canadian Council for Refugees.

Dench blames the Safe Third Country Agreement, a 2004 deal between Canada and the United States that allows Canada to send asylum seekers who enter Canada back into the United States. That agreement has created the demand for false documents and routes through South America, she says.

There is another way of looking at the problem.

Christian Leuprecht, a professor at Queen’s University who did a report for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in 2019 on the massive influx of migrants at Roxham Road, says an open-borders approach does nothing to help really desperate refugees who have fled war and conflict and are living in huge, miserable camps in East Africa and the Middle East.

“The people who are the most in need, either because of their circumstances of persecution or because . . . they’re in some godforsaken refugee camp in the middle of nowhere with no hope of ever getting out . . . are not getting the attention that they deserve.”

Leuprecht thinks we should stem the flow of migrants to Canada by working more closely with security forces in the embarkation countries—something the Harper government prioritized after 492 Sri Lankan Tamils arrived in British Columbia on the cargo ship MV Sun Sea in 2010. Leuprecht adds that we should also make Canada less appealing by deporting false asylum seekers more quickly.

‘How do you properly manage human mobility as it happens today? The idea that the border can be sealed is a fantasy. It’s never happened.’

A 2020 auditor general’s report found that the Canada Border Services Agency removed only 9,500 migrants in 2018-19. The agency “did not remove the majority of individuals who were subject to enforceable removal orders as soon as possible to protect the integrity of the immigration system and maintain public safety,” the auditor general says.

“That’s precisely why Canada is a more attractive target for some groups than the United States,” says Leuprecht, “because they know that you face a much greater chance of deportation from the U.S. than you do from Canada.”

What’s more, there is reason to doubt that our systems for determining who is a real refugee and who is not are working. Alizadeh says none of the migrants she met in South America were real refugees.

“The system no longer has the capacity to really distinguish between people who are genuine refugees from those who are just essentially trying to get themselves a better life, precisely because the refugee system has essentially been abused by that latter group,” says Leuprecht.

Crépeau, the McGill professor, sees it differently. He believes that many asylum claimants are actually just looking for a better life, but anyone would do that same thing in their shoes.

“I would do it,” he says. “If you have to protect your family or feed your children or pay debts or make sure that you can pay the bills for your parents’ health care, that’s what we do. We’ve always done that. That’s what refugees and migrants do all the time.”

He says Canadians should understand that we have designed a system that benefits our own citizens, particularly employers, because undocumented migrants routinely provide low-paying labour without legal protection. “The smuggling industry is offering the service that the market requires, when the state is not offering that service,” he says. “We have to understand that this is very much organized. It’s constructed precarity.”

Crépeau believes the solution is to manage and facilitate labour movements, not pretend we can stop them. “How do you properly manage human mobility as it happens today? The idea that the border can be sealed is a fantasy. It’s never happened. Not even the Soviet Union had secure borders.”

But Canada can’t act alone. Facilitating safe migration must be done internationally, as envisioned by the 2018 Global Compact for Migration, a UN agreement organized in part by former Canadian Supreme Court Justice Louise Arbour. The difficulty is political. Setting aside populists who campaign against immigration, it is hard to build a constituency for reform.

“We don’t vote for migrants and we don’t vote for better policies for migrants,” says Crépeau. “We vote for better policies for ourselves.”

***

Alizadeh decided to get a tattoo at 35, her first, after she was released from prison. It is on her shoulder, covering up a scar from an accident when she was a teenager.

It is a tattoo of a simurg—a mythical Persian phoenix, representing rebirth through fire. “It burns and catches fire and rises from its ashes and flies more powerful than before,” she says.

Alizadeh has left Rio Branco, but is still suffering. (Maclean’s has agreed not to disclose where she is because she fears retribution from the smuggling ring for speaking out.) She is unemployed, broke, lonely and struggling with depression. She misses her friends and family in Iran, but knows she is unlikely ever to live in her home country again. The simultaneous devastation of COVID and the crushing might of Iran’s decades-old theocracy have put a chokehold on relatively normal human interactions and freedoms. Thousands of Iranians are now fleeing to escape not just the pandemic, but also the closeted life in Iran. Alizadeh would likely be arrested upon arrival if she were ever to risk a return.

She often talks about her love of Iran. “My country is in turmoil and I can do nothing for my country. This is the worst possible situation.”

Alizadeh no longer dreams of a new life in Canada; she yearns, instead, for the country to find a way to stop human smuggling and better filter out false claims. “People know that once they arrive in Canada they would be able to get refugee status,” she says, which is “encouraging human smuggling.”

“A large number of Iranians enter Canada with a tourist or student visa and enrol their children in Canadian schools, and then falsely [claim] asylum.”

She hopes her story, this story, helps people understand the misery refugees endure. “I lost my whole life and I have to start again,” she says. “I wish no human had my experience in life.”

This article appears in print in the September 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Escape from Iran.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.