Every 49 minutes

That’s how frequently people died of drug poisoning in Canada during one dreadful week last summer. Here, their mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters share a message: the opioid crisis touches everyone.

(Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

Share

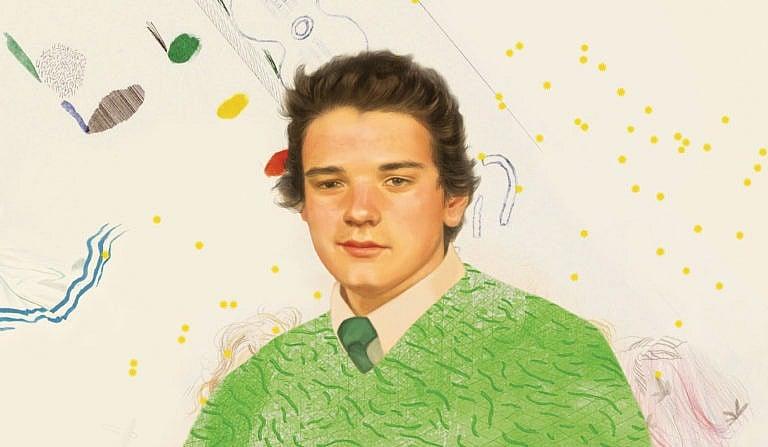

On the football field, Marcus Gould always knew exactly what to do. Everything about the game—physical toughness, endless strategy, the meaning of team—just made sense to him. Even on a roster full of teenage all-stars, No. 88 was special. “On game day, he was the guy the whole team depended on,” says Byron Lott, who coached Marcus on the Oshawa Hawkeyes, an under-16 rep club east of Toronto. “He would run for a touchdown, stay on for kickoff, then play defence. I gave him the option to come out but he never took it.”

Adopted at age one, Marcus was later diagnosed with both ADHD and Asperger syndrome, a form of autism that impacted his ability to socialize. His mom, Tammy, remembers taping up signs all over the house to help “Marky” focus on routine tasks, such as how to pack his school bag. “He was high-functioning in the sense he was very capable of doing things,” she says. “But he had to be coached on every single thing and reminded constantly.”

Yet when he strapped on shoulder pads, something clicked. Quiet but confident, Marcus was in complete control when the whistle blew. “I don’t know what it was,” Tammy says. “I would ask him: ‘How do you remember every single play?’ I had to put notes and pictures on the wall to remind him how to brush his teeth, but he would be telling the other guys where to stand.”

From July 11 to July 17, 2020, toxic drugs killed at least 207 Canadians, according to data compiled by Maclean’s. That is more than 29 people a day, for seven straight days.

Three times, Marcus was selected to play for Team Ontario, and at 16 he suited up for the All Canada Bowl in Chilliwack, B.C. In 2019, at the end of Oshawa’s summer season, the six-foot-one receiver earned the team’s top honour: Mr. Hawkeye. “He was pretty humble, so he didn’t brag about his success,” says his dad, Todd, who owns a landscape construction company. “He always just said: ‘Hopefully I get a scholarship.’ ”

Tragically, that milestone will never come. Marcus died of a fentanyl overdose in Cobourg, Ont., in the summer of 2020—the worst year ever for drug poisoning deaths in Canada. He was 17.

“I still get emails from scouts,” his father says, holding back tears.

The numbers are now painfully clear: last year, as the country rallied to save lives during the pandemic, toxic street drugs wiped out Canadians at a record pace, with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, leading the carnage. All told, confirmed or suspected drug poisonings killed nearly 7,000 Canadians in 2020, or 19 people every day. In Ontario alone, opioids ended more than 2,400 lives, a 60 per cent jump from the previous 12 months. The curve was even steeper in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where fatal overdoses nearly doubled. In British Columbia, where last year’s death toll reached an all-time high of 1,728, toxic drugs now kill more people than murders, car crashes and suicides combined.

No one can pretend to be shocked by the skyrocketing stats. From the early days of the pandemic, harm reduction advocates warned that lockdowns would be disastrous for people who use drugs, shuttering safe consumption sites and limiting treatment options that were already scarce. Far worse, border closures wreaked havoc on illicit supply chains, leading to drug concoctions that have never been so potent and unpredictable. Like thousands, Marcus Gould didn’t stand a chance against the poison he was peddled.

In a year of such relentless loss, the week Marcus died was especially grim—one of the worst seven-day stretches for overdose deaths in 2020, according to data obtained during a Maclean’s investigation. Between Saturday, July 11, and Friday, July 17, toxic drugs killed at least 207 Canadians. That is more than 29 people per day, or one life every 49 minutes for seven straight days. (By comparison, COVID-19 killed fewer than half that many during the same span: 80, or about 11 people per day.)

From big cities to small towns, no corner of the country was spared during that awful week: 64 overdose deaths in Ontario, 48 in Alberta, 43 in B.C., at least 17 in Quebec, 16 in Saskatchewan and 12 in Manitoba. Smaller regions also endured obvious spikes, including New Brunswick (three), Newfoundland and Labrador (two) and Yukon (two). If every week had been so lethal, toxic drugs would have killed nearly 11,000 Canadians in 2020.

Tammy Gould had no idea so many others perished the same week as her son. Told about the data, she pauses for a long time, trying not to cry. “That is a lot of people,” she finally says. “Were they all young like him, or were they older?”

Maclean’s set out to tell that story: one brutal week, amid so many, inside Canada’s other public health emergency—an epidemic that, unlike COVID, has no end in sight.

Because authorities don’t typically release names of overdose victims, Maclean’s spent months searching through thousands of obituaries and speaking to numerous advocacy groups to identify families who lost loved ones between July 11 and July 17, 2020. Many agreed to speak only because they are tired of the stigma surrounding drug use, and furious so little is being done to combat the opioid crisis. They want politicians to embrace safe supply and decriminalization. They want treatment options that are truly accessible. And more than anything, they want the public to realize what is so often forgotten: that each number was a real person, dearly loved and now deeply missed.

“It could be your kid tomorrow,” says Robin Lukash, whose son, David, overdosed on July 14. “That is the reason I’m willing to talk about it: because something has to change.”

SATURDAY

They first met at 14, back home in Halifax. In their early 20s, Christopher Powell-Irving and Justine Cruickshanks made the move to Toronto. “A new start,” as Justine describes it.

Homeless for four years, the couple bounced between shelters and the streets, panhandling for food while chasing their next fix. For them, the opioid crisis wasn’t a headline; it was everyday life. “We knew so many people who overdosed,” Justine says. “I was worried, but it’s all part of being a user, right?”

On July 11, around 5 a.m., the pair huddled in the doorway of a downtown building, their bed for the night. Both smoked what they thought was crack cocaine, unaware it was actually pure fentanyl—a drug so strong that only a few salt-sized grains would be enough to kill most people. “I don’t know if I fell into Chris’s lap or crawled into his lap,” Justine says. “All I remember is saying: ‘I love you baby, I really do.’ And he said: ‘I love you, too. It’s going to be a good night.’ ”

The next thing she remembers is waking up at Toronto Western Hospital. Paramedics were able to revive her using multiple doses of naloxone, or Narcan, a medication that can rapidly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. Her 26-year-old husband was not so lucky.

“We were hoping to get clean, hoping to get a place,” Justine tells Maclean’s, nearly a year later. She is speaking on the same cellphone the hospital gave her when she was discharged. “He was an amazing best friend and he cared so much for a lot of people,” she continues. “Just because we’re homeless and we’re addicts, we still have a life. We still matter.”

In a week that proved so deadly, Christopher Powell-Irving was one of the first to succumb to an overdose. That same Saturday, drug poisonings would kill seven others in Ontario, eight in B.C. and four in Saskatchewan. At least one person died in Quebec, too: Zachary Bonneau, 19.

“My phone rang around 11 a.m.,” recalls his mother, Dominique Allard. On the other end was her ex-husband. “When I heard his voice, I knew something was bad.”

(Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

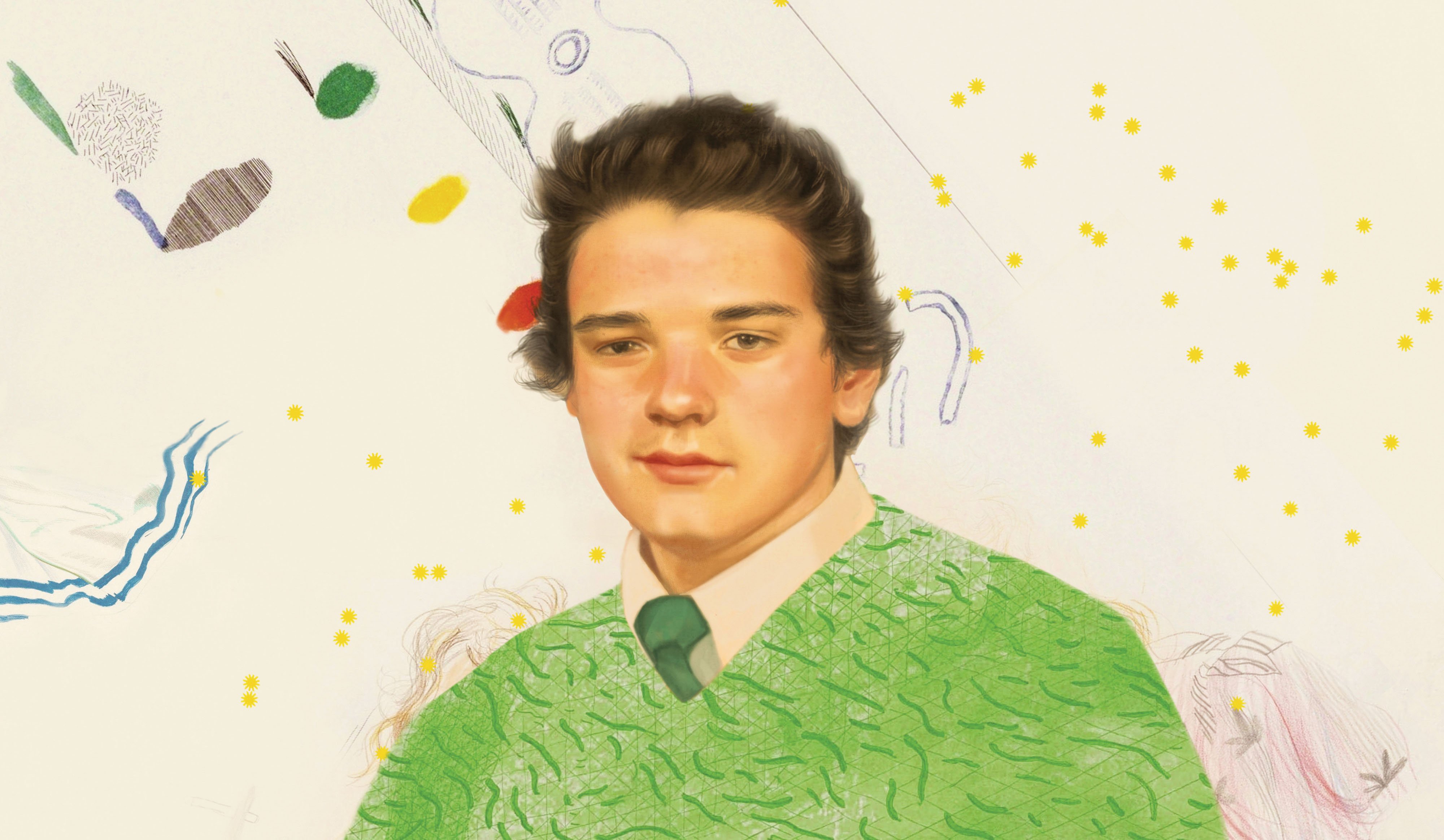

Zachary grew up in Saint-Félicien, a small town on the western shore of Lac Saint-Jean, where his parents owned a country house and a kennel for racing sled dogs. Although he struggled with anxiety, Zachary was very smart; he took enrichment classes in high school and learned three languages (French, English and Spanish).

But by his 18th birthday he was deep into drugs, including meth and cocaine, breaking into houses to feed his addiction. Five months before he died, Zachary told his mother he owed a dealer $2,000. “He was afraid,” she says. “I told him: ‘If you promise me to go to rehab, I will pay the $2,000.’ ” He agreed, but checked himself out less than three weeks later.

Zachary’s body was found in a motel room 30 minutes from his childhood home. He was there with friends, who have since told police he was asleep when they checked on him at 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. When someone peeked again around 7 a.m., he was gone.

More than a year after her phone rang, Dominique is still waiting for another call: from Quebec’s provincial police. She has pushed hard for an investigation, desperate to know if anyone who was at the motel could face criminal negligence charges. “I said to the cops: ‘For you, it’s one less drug dealer,’ she says. “ ‘For me, it’s my lovely boy.’ ”

More than 900 km away, in Cobourg, Tammy Gould set out to meet her son. After months of scouring the city, she had finally tracked him down. “It doesn’t matter what you do for a living or whether you’re rich or poor,” she says. “Drugs touch everybody.”

Shortly after Marcus was named Mr. Hawkeye, something snapped. He became angry and combative, rarely leaving his bedroom. In March 2020, right after the pandemic hit, he went out with some friends and never came back. “I drove the streets looking for that kid,” his dad says. “I knew he had gotten into drugs so that concerned me, obviously. But it was the fact we couldn’t find him.”

“I said to the cops: ‘For you, it’s one less drug dealer. For me, it’s my lovely boy.’ ”

Because Marcus was older than 16, he was legally free to leave home. As a result, his parents say their pleas for help were repeatedly brushed aside by police and other social service agencies. “I was just worried sick,” Tammy says. “I went to hotels looking for him, I went to Children’s Aid. I was down at the river looking for him.” She also made regular stops at Marcus’s high school, which the city used as a temporary homeless shelter during COVID. One day, a man there pointed her to a nearby building, where electricians were working. None of them had seen Marcus, but one worker promised to contact Tammy if he turned up.

“Sure enough, the next day, the guy texted me,” she says. Tammy drove straight over, eventually spotting her son walking outside. “He wouldn’t look at me, he was so embarrassed,” she recalls. “I made him hold my hand and I said: ‘You’re going to come to lunch with me tomorrow.’ He said he would.”

The next day, Saturday, July 11, Tammy and Marcus ate Subway on the tailgate of her pickup truck. For the first time in so long, she felt a sliver of hope. “I asked him to have lunch with me again on Sunday,” Tammy says. “He agreed.”

SUNDAY

The gusts were heavy that morning, as usual. “They say that 60 per cent of the time, the wind here is blowing at least 60 km an hour,” says Lori Vrebosch, who lives on Piikani Nation in southern Alberta. “So it was about regular that day.”

The cars began arriving around 9 a.m., each carrying a different family devastated by overdose. As planned, they were gathering for a sombre photo shoot organized by Moms Stop the Harm, an advocacy group that supports grieving relatives while lobbying hard for decriminalization and safe supply. “We had talked about doing a photo in this area, so I threw it out there: ‘Maybe we should have it on a First Nation?’ ” Vrebosch says. “Maybe we should talk about the suffering of the Indigenous people.”

By every available metric, the opioid crisis has hit Indigenous Canadians much harder than anyone. In B.C., First Nations people are 5.3 times more likely to suffer a fatal overdose, while in Alberta, that number is even higher (7.3 times more likely). A recent report from the Alberta government found that, during the first six months of 2020, the rate of opioid-related deaths among Indigenous people was 112 for every 100,000; the death toll for everyone else was 15 per 100,000. To put it another way, Indigenous Albertans make up only six per cent of the province’s population, but accounted for an astounding 22 per cent of all drug toxicity deaths between January and June of 2020.

“Everyone agrees that COVID-19 is a global pandemic that warrants the attention it has received, but we’re dealing with dual public health emergencies and we just haven’t seen the same kind of attention being paid to the toxic drug crisis,” says Nel Wieman, acting deputy chief medical officer at the First Nations Health Authority in B.C. “We’ve seen the messaging for COVID: ‘We’re all in this together. Let’s look after one another.’ But the unspoken messaging around the toxic drug crisis is: ‘I’m glad it’s you and not me.’ ”

On Piikani Nation, it’s hard to find a family not ravaged by opioids. In the two weeks leading up to the photo shoot, at least four residents died of an overdose; two days later, another woman became a statistic. “The whole point of the photo was to show that this is a fight we all share,” says Vrebosch, who lost her son to fentanyl in 2018. “We had a really good blend of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people come together that day. We bleed together, we cry together, and it will take everybody’s hands held together to try to end this thing.”

For Brent Russell, July 12 was just the beginning of his grief. It was the day he learned his little brother was gone, discovered the previous day at a supportive housing complex in Red Deer, Alta. He was 31. “It was a shock,” Brent says. “The hardest thing I’ve ever learned is how to talk about Clayton in the past tense.”

“The unspoken messaging around the toxic drug crisis is: ‘I’m glad it’s you and not me.’”

The youngest of three brothers, Clayton Russell was raised by his mom and stepdad in Quesnel, B.C., where he spent his childhood riding snowmobiles, playing hockey and delivering the local newspaper. But by Grade 9, drugs had taken hold, and he soon skipped town to join a travelling carnival. Although Clayton later moved to Calgary, where he worked for a time as a welder, addiction dominated his days. “Lots of people turned their backs on him,” says Brent, who still lives in B.C.

Brent kept in regular contact with his brother, both by phone and on Facebook, especially after their mom died in 2011. Whenever they spoke, Brent always made sure to tell Clayton he loved him, and wouldn’t hang up until his brother said it back. “All that nonsense I had to do—topping up his jailhouse bank account, tracking him down—was worth it, because no one else got an ‘I love you’ out of him.”

Back in Cobourg, Tammy Gould met Marcus for the second straight day. They sat in a park eating Swiss Chalet. “He told me he knew what he was doing was wrong, and that he was coming home that week,” Tammy recalls. “I know they always say that, but my intention was to keep pushing for it. I told him to get his stuff ready.”

As they ate, another body was waiting to be found.

Seth MacLean grew up in west-end Toronto, a popular kid who loved basketball and rap. It wasn’t until high school that everything changed. “He started acting like he didn’t want to be around people anymore, which was very out of character for him,” says his mom, Nerissa MacLean. “His behaviour became so bizarre.”

Seth Maclean. (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

Seth was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a heartbreaking blow to his entire family. “He wanted to do normal things,” says his uncle, Tyson MacLean. “But he didn’t like the effects of the medication they put him on. He said it made him feel like a zombie.” He told his mom it felt like something was crawling all over him.

Seth chose to self-medicate instead, first with weed, then crack cocaine. By 2014, he was living on the streets and well-known to police, arrested more than 100 times.

Although he refused to live with his mom, she never gave up on him. For years, Nerissa would drive around downtown Toronto so she could lay eyes on her son. When she couldn’t find him, she would search the usual places: hospitals, shelters, the courthouse. “It was just routine,” Tyson says. “Nerissa would text me a picture of him and say: ‘I talked to Seth today.’ ”

At 1:30 p.m. on July 12, Seth was found dead at a Toronto shelter, dressed in a black tracksuit. For the next 45 days, his corpse remained at the provincial coroner’s office; his family was not contacted. Seth was eventually buried, naked, in an unmarked grave—Plot 536—at a cemetery in Pickering, Ont.

Nerissa had no idea her son was dead until Sept. 10, on what would have been Seth’s 32nd birthday. Unable to locate him for weeks, she finally turned to the police for help. “They said: ‘I’m sorry to tell you this but your son passed away on July 12 of a drug overdose,’ ” she says. “How do you bury somebody and not even find their next of kin?”

MONDAY

William Teahen-Jones worked for a lawn care company in Collingwood, a ski resort town two hours north of Toronto. When he didn’t show up for his Monday morning shift, his mother immediately feared the worst. “My son was a beautiful person, his soul was beautiful,” says Jane Teahen. “But he was very vulnerable.”

From a young age, William struggled mightily with mental illness. Arrested multiple times, once for walking in the middle of a busy highway, the 37-year-old had been recently discharged from a psychiatric hospital. He had multiple diagnoses, including autism, depression and substance use disorder. “People have this attitude of: ‘They are addicts, they deserve to die,’ ” his mom says. “But they are ill. They have a disease.”

William Teahen-Jones. (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

So many still have a hard time grasping that fact: addiction is an illness, not a lifestyle choice. Simply put, opioids activate certain receptors in the brain, triggering powerful feelings of euphoria. The more a person uses, the more they need. Little else matters. “People think addiction is a moral failing but we know that’s not true,” says Dr. Monty Ghosh, an addiction specialist at the University of Alberta Hospital. “Substance use disorder is basically a biological process in which the pathways of reward in the brain get hijacked.”

No segment of society is exempt. Although research shows that opioids are most likely to ensnare vulnerable men like William Teahen-Jones, the epidemic does not discriminate, targeting every age, skin colour and salary. “A lot of people using substances have experienced trauma in the past,” Ghosh says. “They’ve been physically, emotionally or sexually assaulted, or they’ve dealt with pain on a regular basis. Using these substances is the first time in their life they’ve ever felt good.”

In a cruel twist of timing, it appeared that opioid-related deaths were finally starting to drop right before COVID struck. After surging every year between 2016 and 2018—from 2,825 to 3,916 to 4,389—the annual death toll fell in 2019, to 3,830, according to data compiled by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Then came 2020. The final tally for the year, released in June, annihilated all previous levels: 6,214 Canadians killed by opioids.

Even that number, as unimaginable as it seems, doesn’t tell the whole story. Although opioids are the prime culprit in the overdose crisis, hundreds were also killed last year by stimulants, including meth and cocaine. Add in that figure—which most provinces do, in the overdose stats they publicize—and the body count from toxic drugs was closer to 7,000. The vast majority of those deaths occurred in six provinces: Ontario (2,426 fatalities, up 60 per cent from the previous year), B.C. (1,728 deaths, up 75 per cent), Alberta (1,331, up 67 per cent), Quebec (547, up 32 per cent), Manitoba (372, up 87 per cent) and Saskatchewan (336, up 90 per cent).

While researching this article, Maclean’s asked those six provinces to provide a list of its deadliest days in 2020. Most agreed. In B.C., for example, May 28 was the worst 24 hours for drug poisoning deaths, with 15. On April 30 in Ontario, 14 people died of an overdose. In Saskatchewan, toxic drugs killed five people a day on multiple days.

But as the daily numbers trickled in, the data revealed something else: that dreadful week in mid-July. In one three-day span, the 14th to the 16th, Alberta alone lost 27 people to opioids.

Maclean’s then asked the other provinces and territories to provide overdose stats for the same seven days. Citing privacy concerns, most would disclose only the total number of deaths for the week, not a daily breakdown. The final tally: at least 207 overdose deaths in a single week.

“We were already in a total train wreck with the drug supply being so toxic,” says Donald MacPherson, executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. “And then the pandemic came along and just ripped the lid off the whole thing.”

Tragically, the same public health measures meant to protect Canadians from the virus (lockdowns, physical distancing, self-isolation) made life even more precarious for drug users. Unable to access vital services, such as overdose prevention sites, many were forced to inject or smoke alone, all while the country’s illicit supply grew more dangerous by the day.

“People think addiction is a moral failing but we know that’s not true,” says Dr. Monty Ghosh, an addiction specialist at the University of Alberta Hospital. “Substance use disorder is basically a biological process in which the pathways of reward in the brain get hijacked.”

With borders closed and smuggling routes clogged, criminal syndicates improvised—with catastrophic results. In one alarming trend, coroners have found increasing cases of fentanyl cut with benzodiazepines, or “benzos,” a class of tranquilizer. (Naloxone does not work on benzos, making it much harder to reverse an overdose.) In so many other cases, recreational users are buying what they think is cocaine or crystal meth, oblivious to the fentanyl mixed inside.

“We’ve seen the composition of drugs change radically during the pandemic,” says Tim Slaney, a prominent harm reduction advocate in Lethbridge, Alta., which last year endured the highest rate of fatal overdoses in the province (53 in a city of 100,000). “This isn’t people taking a little bit too much because they overestimated their tolerance. This is poisoning. These are drugs people don’t know they’re taking, and wouldn’t take if they had a choice.”

On July 13, as Jane Teahen tried to track down her son in Collingwood, the opioid crisis continued to wreak havoc across the country, unforgiving as ever. In B.C., paramedics responded to 78 potential overdoses—another brutal day in what would become the province’s busiest-ever month for overdose calls (more than 2,700). In Saskatoon, medics worked on a victim who needed eight doses of naloxone to snap back to life. And in Windsor, Ont., health authorities issued a public alert about “high rates of drug-related overdoses” following a weekend that saw nine fentanyl poisonings.

“It is relentless, and it’s continuing to get worse,” says Dr. Dirk Huyer, Ontario’s chief coroner. “It is very difficult to see so many young people dying on an ongoing basis, and they’re dying from something that is preventable.”

William Teahen-Jones didn’t go to work that Monday morning because he was already dead, lying alone in a Scarborough, Ont., apartment. His mother wouldn’t learn the truth for another week, when police visited her townhouse to break the news. “He was apparently found with a needle sticking out of his arm, that’s all I know,” Jane says. “He was a vulnerable person so it was like giving poison to a baby.”

Myanna Dreaver. (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

TUESDAY

Myanna Dreaver was a talented artist and a stylish dresser, a woman who loved to cook and sing and ask a million questions. “She was a great companion on road trips, and never ceased to be amazed by the majesty of the mountains,” says her mom, Gayle Graham. “She had a knack for noticing the unusual, and she had a great, booming laugh.”

Dreaver also believed, deep down, she would beat her disease. An addict for 25 years—bouncing in and out of jail, detox and rehab countless times—she never lost hope in tomorrow. “Myanna tried hard to be like everyone else,” her mother says. “Looking back, there was no way for her to win.”

On July 14, a cloudy day in Edmonton, the three of them met at Newcastle Pub and Grill: Gayle, Myanna and Myanna’s teenage son, Dainek, who lives with his dad. Myanna lost custody of her son years ago, another casualty of the disease, but they remained close. “It was a really great lunch,” Gayle recalls. “Most of the conversation was Myanna asking Dainek questions. She always wanted to know everything about him.”

Immersed in conversation, no one at the table thought to snap a photo. “I wish I did,” Gayle says. “Who knew it was going to be our last one?”

A few hours away, down Highway 2, Christina Edwards received a knock at the door. It was Calgary police, confirming her worst fear: her niece was dead, discovered that morning inside her locked apartment. “She would call me ‘Auntie,’ ” Christina says. “But really, I was more of a mother figure to her.”

Kristen Black Rider-Papequash—Sky, as everyone called her—grew up in foster care, transferred from home to home again and again. Her passion was fashion, especially when it meant helping her many friends look gorgeous. “She loved Louis Vuitton and Gucci clothing and practically every expensive perfume,” Christina says. “She enjoyed watching the Kardashians, if that gives you any indication of how she was.”

Kristen Black Rider-Papequash (Sky). (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

When COVID hit, Christina called and texted often. Sometimes Sky responded right away; other times, not for a week. On July 7, Sky’s 30th birthday, all of Christina’s messages went unanswered. “I contacted her landlord to see if they could go check on her, but her door was locked and there was nothing they could do,” she says. “I had to call the police.”

Sky’s obituary said she died on July 14, the day police found her. Like so many overdose victims, she was alone when she took her final breaths. “Please don’t look down on addicts,” Christina says. “There is someone out there who loves them. They are someone’s child, someone’s mother or father. They belong to someone.”

One province over, on Vancouver Island, an afternoon protest was growing bigger and louder. Fed up with opioids being pushed on their reserve, a few dozen members of the Cowichan Tribes, B.C.’s largest First Nations band, made a bold decision: to confront the drug dealers in person. Waving cardboard signs and beating drums, the group descended on three houses where dealers were believed to be living. “You’re killing our people!” one man yelled. Nobody inside dared to come out.

“The reaction was very positive, both on and off the reserve,” says Joe Thorne, a Cowichan Elder who organized the protest. “As we marched through town, people came out and said: ‘Thank you. We need this. We want our community back.’ ”

Among those in the crowd that Tuesday was a grieving father named Clyde Johnny. A few days earlier, on July 10, he lost his daughter, Fairlie, to an overdose. She had just turned 14. “I questioned her all the time,” Johnny tells Maclean’s, holding back tears. “I told her: ‘Don’t be doing drugs, baby,’ and she gave me all the answers I needed to hear. She would say: ‘No, I’m not doing that, Dad.’ ”

“This isn’t people taking a little bit too much because they overestimated their tolerance. This is poisoning. These are drugs people don’t know they’re taking, and wouldn’t take if they had a choice.”

Fairlie’s older brother found her in her bedroom, a glass pipe nearby. “My daughter was just so kind, happy and loving,” her dad says. “I really miss her.”

The protesters had no way of knowing, but their march occurred on yet another terrible day across the country: 10 fatal overdoses in Ontario, seven in Alberta, at least one in Manitoba and seven more in B.C.—including David Lukash, an aspiring writer from Kelowna.

“It’s infuriating,” says Robin Lukash, David’s mother, when told the numbers. “We talk about COVID all the time and we’re accountable around COVID, but what about opioids? People are being poisoned. Could you imagine right now if somebody was drinking a Bud Light—and sometimes they died, and sometimes they didn’t? It would be a national catastrophe.”

David grew up riding skateboards and driving stock cars, always pushing the limits. He worked in sales for a while, but wrestled with alcohol addiction and mental illness, including bipolar disorder. Writing was such a devotion—poetry, songs, plays—that the 37-year-old had recently enrolled in the bachelor of arts program at UBC Okanagan. “He had bits of paper all over the place with lyrics and verses and ideas,” his mom remembers. “One of the things he said a lot was: ‘My heart is your home.’ He used that phrase with everyone. ‘My heart is your home.’ ”

David ate dinner at his parents’ home on July 14, then his mom drove him back to his place. On the way, they stopped for groceries at a Safeway, one block away from the Kelowna rooming house where he lived. It was a gorgeous night, perfect summer weather. “When we left the store, I said: ‘Do you want a ride?’ He said: ‘No, no, I’m going to walk.’ I said: ‘Okay, I love you.’ He said: ‘I love you, too, Mom,’ then gave me a big hug.”

Robin watched her son walk away, grocery bags dangling from each hand. He turned and waved one more time.

The coroner concluded that David took cocaine laced with fentanyl. When he was found in his room, his groceries were still in the bags.

Marcus Gould. (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

WEDNESDAY

Tammy Gould rushed to answer the door. It was early, not quite 8 a.m. Her younger son was still in bed and Todd had already left for work. “It was a police officer,” Tammy recalls. “All she said was: ‘I need you to come with me now.’ ”

Earlier that morning, paramedics were dispatched to a rooming house in Cobourg, where Marcus was found VSA (vital signs absent). Although medics worked frantically to restore his breathing, the 17-year-old football star was barely alive as the ambulance arrived at a local hospital. “He was on machines and they were working on him,” Tammy says. “They said to me: ‘Even if we get him back, he won’t be the same. His brain has been damaged.’ Selfishly, I just kept saying: ‘I don’t care, I just want him back.’ ”

Only three days earlier, Tammy had been eating lunch with her son, listening to him talk about finally coming home. By then, football was the furthest thing from her mind. She just wanted Marcus to feel safe, to know how much he was loved.

“I still get emails from scouts.”

“The doctors worked on him until noon,” Tammy says. “We watched while he died.”

Toxic drugs killed 10 other people in Ontario that Wednesday. Across the country, 11 more died in Alberta, four in B.C. and four more in Saskatchewan—making July 15 one of the worst days of the year for overdose deaths in Canada, with at least 30.

“It makes me feel sick,” says Ramona McKnight, whose father, James, was one of those numbers. “I honestly don’t know how to feel about it.”

As a child, Ramona did not know her father; she only knew of him. Though born in Saskatchewan, James, who was Cree, grew up in California before hitchhiking his way back to Canada as an adult. In and out of prison, he had no contact with his daughter for nearly a decade. “He came back into my life after he got out of jail,” Ramona says. “When I was 11, he basically said to my mom: ‘You know, I think I would do better if I had one of my children living with me.’ ”

Ramona jumped at the idea, excited to get to know her dad. They moved to a small house in Regina. “It was just the two of us, and we had a very special bond,” Ramona says. “My dad had a lot of past traumas he refused to talk about, but he was very loving. He would always tell me: ‘I pay the bills, I provide your clothes, the only thing you have to do is go to school.’ ”

Although he never discussed his addiction issues with Ramona, James made it clear he wanted better for his daughter, constantly encouraging her to graduate high school and choose a rewarding career. What James didn’t realize was that his own actions, not his words, were already having a huge impact. “When I was 15, we lived with my uncle and my grandmother all in one house, and my dad took care of them,” Ramona says. “It inspired me to get into health care. If it wasn’t for my dad, I would not be working in health care.”

Now 31, Ramona is a continuing care assistant in Indian Head, Sask., where she works with the elderly. “My dad pushed me,” she says, starting to cry. “He made a difference in my life. That is why I do what I do: to make him proud and let him know he raised a good girl.”

James was 56 when fentanyl ended his life inside a Regina rooming house. That same morning, 30 minutes northeast of the city, the overdose crisis claimed yet another victim: Travis Tumach, found dead in the small town of Zehner. “My son died alone,” says his mother, Sabrina Tyrell, “like an orphan dog in the middle of nowhere.”

Born in Saskatchewan, Travis moved with his mom to Nashville, Tenn., when he was 10. Seeking a fresh start after numerous run-ins with the law, he returned to Canada in his early 20s. Unfortunately, his troubles followed. In the days before he died, the 29-year-old was so paranoid about a debt he owed to a Regina drug dealer that he changed his Facebook profile to say he’d moved to Vancouver.

“He had hopes and dreams just like everybody else,” his mom says. “He would often tell me: ‘You know, if I can get through this, I want to be a drug counsellor and help other people because I know how horrendous this is.’ But that’s the thing about addiction: it was stronger than he could control.”

Back in Toronto, Seth MacLean’s corpse was wheeled in for an autopsy. Dead for three days, he had a coroner’s ID tag hanging from his left wrist. “He was found unresponsive on his mattress by another resident in a men’s shelter with drug paraphernalia present,” reads the coroner’s report. “Considering the history, circumstances and postmortem examination findings, death is attributed to fentanyl and cocaine toxicity.”

What remains much less clear is why Seth was unceremoniously buried 45 km outside of the city, without authorities ever alerting his family. If police or the coroner’s office had followed standard procedure, they would have easily found his mother’s phone number at the Office of the Public Guardian, which handled Seth’s disability cheques. “But they didn’t do that,” Nerissa says. “They didn’t do anything. The cop who attended the scene where Seth was found knew him, stigmatized him, and that was it.”

Dr. Huyer, Ontario’s chief coroner, admits “there were gaps” in how Seth’s case was handled, and says he is grateful to the family for exposing systemic problems that needed to be fixed. “I have to tell you that my intersection with Seth’s family has been very impactful in a good way,” Huyer says. “From my point of view, Seth will live on in name, and as a legacy, in our system. He and his family made a difference to how we approach trying to find next of kin.”

THURSDAY

Growing up, Myanna Dreaver loved the country tune Delta Dawn by Tanya Tucker, with the line: “She’s 41 and her daddy still calls her ‘baby.’ ” “We both used to sing along to that song, and I always told her she would still be my baby when she was 41,” says her mom, Gayle. “Her 41st birthday would have been Aug. 13, 2020.”

Myanna died at 40. Her body was discovered on the morning of July 16, less than one month before her birthday—and just two days after she met her mother and son at that Edmonton pub. “It’s what you read about all the time: people think they’re taking cocaine, but it’s pure fentanyl,” Gayle says. “When I talked to her son, obviously we were both crying. He said: ‘You know, I’m really glad we went for lunch.’ ”

That Thursday, like the day before, was one of the deadliest 24 hours of the year for drug poisonings: at least 31 fatalities across the country, including nine in Alberta, five in B.C., four in Saskatchewan and one in Manitoba. In Ontario alone, 12 people died of an overdose—one every two hours.

Among those dozen was Michael Jacques, 53, of London, Ont. “He died in a dark place, and it wasn’t all his fault,” says his older sister, Jacqueline Jacques. “All these people doing drugs, they’re out there because something has gone wrong, and we’re not giving them the grace they should have to live a normal life.”

Like his sister, Michael was a gifted artist with huge potential. His sketch work was exceptional, and after high school he was offered the chance to attend a prestigious art college in Montreal. But he also harboured a deep secret that altered his path: as a child, he endured repeated sexual abuse at the hands of a babysitter. “Michael never got help for what happened,” Jacqueline says. “He said he was fine, that he knew how to deal with it, but his way to deal with it was to almost drop off the face of the earth.”

Michael battled addiction his entire adult life. At his funeral, Jacqueline made sure everyone knew the cause of death. In her mind, Michael had suffered enough in life; in death, he didn’t deserve people’s shame or judgment. It’s the same reason she agreed to speak to Maclean’s. “This is the most important thing I’m going to do for my brother and for other people,” she says. “If I could help one person—if this article is out there, and one person reads it and figures out a way to help somebody—I’m all for it.”

An hour away, at a townhouse in Brantford, Ont., another victim, another 911 call. Another name added to the ever-growing list.

A welder by trade, Jamie Dee Taylor was an expert in custom-built fabrication, especially motorcycles. His creations were phenomenal, more art than machine. “He worked for some incredible companies and was very accomplished,” says his older sister, Sheila Taylor. “He built things that took real skill.”

But behind Jamie’s exceptional talents were deep insecurities. Diagnosed with dyslexia as a child, he once heard a teacher describe him as functionally retarded. “As he got older, his demons got bigger and his struggles got bigger,” Sheila says. “When he had great moments of clarity, he loved his family and he had great ideas and ideals. But when he was gripped by his demons, he had shame and guilt. He would talk openly about feeling the stigma of addiction.”

In those moments of clarity, Jamie would turn to his big sister for help. He tried every tactic over the years: detox, day programs, white-knuckling in one of Sheila’s spare bedrooms. “But guess what?” Sheila says. “Your window of opportunity is about an inch, and guess how long you have to wait to get a bed? People watch television, they see Intervention, and they think it’s just that easy to get help. It’s not.”

In recent years, as Jamie plunged deeper into addiction, Sheila did not see her brother. That Thursday, a roommate found him unconscious at around 11 p.m. He was 43.

“The person I knew died a long time ago, so I grieved the loss of that person a long time ago,” Sheila says. “What happened on that day—the day I found out he was dead—was that hope died. As long as Jamie was still here, there was hope it was going to get better, that he would find his way to a treatment program that worked, that we would have a relationship again. There was still hope. But the minute his spark of life was extinguished, hope died.”

Hayden Robson. (Photo illustration by Hsiao-Ron Cheng)

FRIDAY

Hayden Robson was a big guy and a bigger personality—“handsome as hell and really kind,” as his mom, Cherith Robson, puts it. “He used to collect all the rough ones at school, and if a friend was struggling, he would always figure out a way to help.”

Last summer, Hayden was the one struggling, barely hanging on. What began with some casual cocaine at a party had spiralled out of control. “He was so scared he was going to overdose,” Cherith says. “As a mother, it’s the most hopeless, helpless feeling.”

In late June, the 27-year-old checked into a treatment centre in Surrey, B.C. He lasted four days. By July, Hayden was back at his mom’s house in Penticton, B.C., counting down the hours until his follow-up appointment at a local addictions resource centre. “The appointment was scheduled for July 23,” Cherith says. “He was really looking forward to that damn appointment.”

It never happened. On the morning of July 17, six days before the appointment, Hayden died in his bedroom—one of seven fatal overdoses in British Columbia that Friday. Toxic drugs killed six others in Ontario, five in Quebec and one in Saskatchewan. “It’s like the mass shootings now,” Cherith says. “Every day, you hear about another overdose. Are we that desensitized?”

“He was handsome as hell and really kind. He used to collect all the rough ones at school, and if a friend was struggling, he would always figure out a way to help.”

Hayden smoked fentanyl and never woke up. He tucked his pipe into a bag of chips, hoping his mom wouldn’t find it. “The worst part was when they took him away,” Cherith says. “It was just absolutely horrifying to see him in that bag. It wasn’t even an ambulance, just a van. They put him in and he was gone.”

Four provinces away, in Toronto, public health officials issued an urgent warning that Friday: 15 suspected overdose deaths during the previous eight days, the “worst cluster” ever recorded in Canada’s biggest city. Although the alert did not identify any of the 15 victims, one was Christopher Powell-Irving, the homeless man who overdosed on July 11. If paramedics had not managed to revive his wife, 15 would have been 16.

“You can get lost in the numbers, and you can also start to become numb to the numbers,” says Joe Cressy, chair of the Toronto Board of Health. “The overdose crisis is an epidemic, and the only distinction when you compare it to COVID-19 is that governments don’t tackle it with the same urgency. If we had hundreds of people dying on a monthly basis from any other preventable cause, governments would have solved it a long time ago. But because it’s drug use, and because of the stigma associated with drug use, people continue to die needlessly.”

That Friday night, back in British Columbia, a few friends knocked on Cyrus Burr’s door. An aspiring cook, the 19-year-old had recently moved into a new apartment near Vancouver’s Gastown district. “They were going to hang out that night,” says Cyrus’s aunt, Candice Ellingson. “He didn’t answer the door.”

Growing up in east Vancouver, Cyrus liked to push the envelope, usually on his skateboard. Fractured bones were all part of the adventure. But he was a thoughtful kid—“an old soul,” his aunt says—who knew exactly what career he wanted to pursue. Juggling two restaurant jobs, Cyrus was working toward his certificate as a Red Seal chef.

Candice last saw her nephew in December 2019, the Christmas before COVID. “I really love cooking, so we talked a lot about how excited he was to be in the industry and how it was a really innovative space these days for master chefs,” she says. “He was so passionate and I was very excited for him.”

They made guacamole together, sharing tips as they tossed in different ingredients. “I’m really grateful for that time we had,” Candice says. “He’s not just a number or a stat. He was a human being and he was loved.”

The landlord unlocked Cyrus’s door. Cocaine cut with fentanyl, yet again. In his obituary, Cyrus’s family was viciously honest: “Taken away too soon by the opioid scourge.”

EPILOGUE

The package was left on the front porch, no signature required. When Sabrina Tyrell first spotted the box—her son’s ashes, mailed from Regina to Nashville—her mind instantly flashed back to Travis as a teenager, always forgetting his house key. “He would be locked out and I would find him on the porch,” she recalls, fighting back tears. “I thought: ‘Oh God, what I wouldn’t give for you to be here like that, not like this.’ I sat on my steps and held my boy in my arms. I just hugged the box and cried.”

Today, more than a year later, Canada’s overdose crisis rages on, minute by minute, coast to coast. In B.C., toxic drugs have already ended 851 lives in the first five months of 2021—a pace that would eclipse last year’s record high—while early numbers from Alberta and Saskatchewan point in the same grisly direction. National modelling projections, released in June by PHAC, show that opioids could kill up to 2,000 people each quarter this year. That would equal 8,000 more bodies, or nearly one overdose death every hour of 2021.

More than a year later, Canada’s overdose crisis rages on, minute by minute, coast to coast. National modelling projections, released in June by PHAC, show that opioids could kill up to 2,000 people each quarter this year.

“You’re writing about one week, but we all know that every week is a bad week, that every day is a bad day,” says Arlene Last-Kolb, co-founder of the advocacy group Overdose Awareness Manitoba. “We are accepting the unacceptable.”

What should be done? Ask any expert and the answers are the same. Decriminalization for personal use. Increased funding for proven harm-reduction measures. Safe supply—a legal, regulated alternative to the crime syndicate poison that’s killing so many. Simply put, governments need to start treating the overdose crisis for what it is: a public health emergency that warrants a COVID-like response.

“People say we have to scale up our addiction programs,” says MacPherson, of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. “Well, that’s a good thing to do, but it’s not an emergency response. People will die tonight in Canada. Surely to God, shouldn’t we be trying to offer them something that’s not laced with fentanyl, without judgment?”

Are some lives not worth saving? If the cause of death is poisoned drugs, is it easier to look away?

“It was actually a big shock to me that nobody cares about this issue,” says Cherith Robson, Hayden’s mom. “I’m honestly overwhelmed by the lack of empathy and compassion. I’ve actually heard people say: ‘This is just nature taking its course.’ ”

Nerissa MacLean has confronted the same kind of stigma, again and again. A crisis worker at a Toronto hospital, Seth’s mother deals with mental health emergencies every day—patients just like her son. “People don’t choose to be an addict, and they don’t choose to live on the street,” she says. “And don’t think the people out there don’t have somebody, because everybody has somebody.”

Today, Seth is still buried at Duffin Meadows Cemetery in Pickering. The coroner’s office offered to exhume his body and rebury him closer to home, but Nerissa ultimately decided against it. “It was a decision I didn’t make lightly,” she says. “But you know, it is a peaceful place. When I am there, I feel like I’m actually with Seth.”

Twenty minutes from the cemetery, driving east, is the Civic Recreation Complex, home of the Oshawa Hawkeyes. On Aug. 8, 2020, a sunny Saturday, the football field was reserved for Marcus Gould’s memorial. Because of COVID restrictions, mourners had to shuffle through in shifts, 100 at a time every hour.

“They have to make changes,” Tammy Gould tells Maclean’s. “This isn’t about the loss of a child, this is about the loss of a family. It is not just the victims who die.”

Since Marcus passed away, Tammy has been advocating for a Canadian equivalent of Casey’s Law, a U.S. statute that allows parents to seek court-ordered drug treatment for their adult children. A Facebook page she created, “MarkyMattered,” includes a petition with nearly 800 signatures. “We had no chance of helping him because we did not have the right to act on his behalf,” she says. “Nobody would help me. All I kept hearing was: ‘Our hands are tied.’ ”

The football-field memorial included life-sized photographs of Marcus, each wearing a different all-star uniform. At the 55-yard line, a long table showcased his many trophies and medals. In the middle was Marcus’s custom-built urn, silver like a Super Bowl trophy and topped with his blue and white helmet.

This article appears in print in the September 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Every 49 minutes.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.