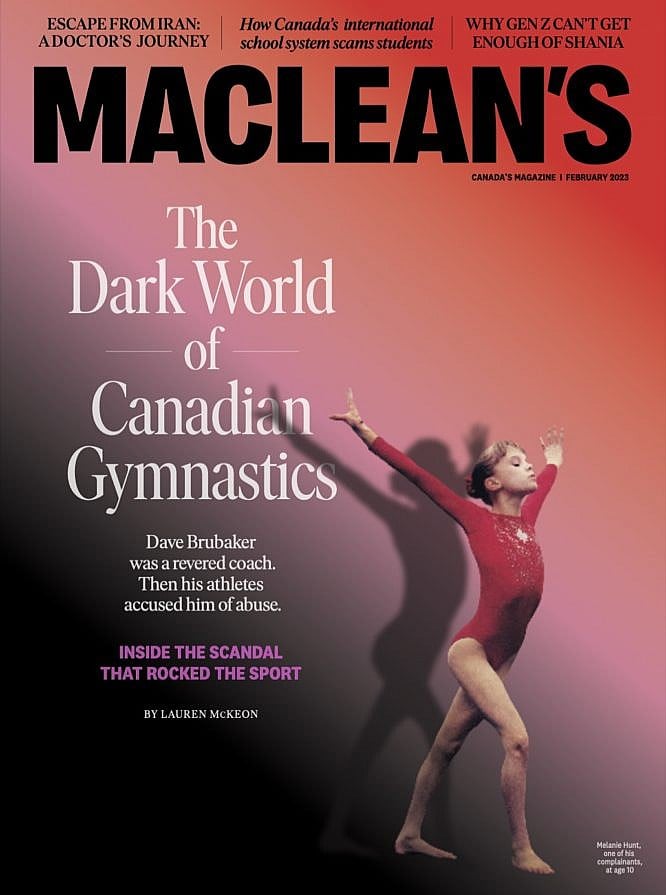

My Escape From Iran

I worked at a prosperous medical clinic in Iran. When the protests began, the regime came for me. This is how I escaped.

(Photography by Grant Harder)

Share

In order to protect his identity and his family’s, Maclean’s has only included Mohammadreza’s first name in this piece.

It was seven in the evening late last September, just after sunset. I was getting ready for my last two patients of the day when my assistant walked into my office. “Doctor,” she said, “Can you come to the laser room? It’s better if you hurry.”

I worked at a small clinic in Karaj, a city west of Tehran, where we performed simple cosmetic procedures like Botox and lip injections. It wasn’t the kind of place where we saw a lot of emergencies, but I could tell from my assistant’s tone that something was amiss. She led me to the little room where we performed laser hair removal. There I found a boy, about 10 or 11 years old, and his father, who had draped a coat over the child. When he removed it, I could see the boy’s back was covered in blood, his shirt riddled with bullet holes. My heart began to beat faster, and I could feel my muscles tighten.

“What happened?” I asked. But I already knew. For days, protests had raged through the city and the country over the death of a 22-year-old woman named Mahsa Amini. On September 13, Amini and her family were visiting Tehran when they were stopped by the country’s Guidance Patrol—the government’s morality police, who enforce public behaviour in compliance with ultra-strict Islamic orthodoxy. They arrested Amini on the grounds that she was wearing her hijab improperly, and witnesses said they beat her before dragging her into a van. Hours after her arrest, she was taken to hospital, where she fell into a coma. On September 16, she died. Police said it was a heart attack.

Anger at Iran’s repressive, theocratic government has been simmering, and boiling over in protest, for years. But Amini’s death—its brutality and ugliness and pointlessness—touched a raw nerve. The day after she died, the funeral in her hometown of Saqqez attracted protesters who removed their own hijabs in solidarity. At some point, police fired on them—an early volley of violence in a standoff between regime forces and citizens. In the months since, countless Iranians have marched in the streets, and hundreds have lost their lives in clashes with government forces.

This boy and his father hadn’t been taking part in the protest. “We were just there to see what was going on,” said the father. “We were only curious.” But when the police began shooting, everyone was caught in the line of fire.

Our clinic was the furthest thing from a trauma centre, but it was clear why this pair had stumbled through our door as they fled: the hospitals weren’t safe, packed with officers from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC, who arrested people showing up with protest-related injuries. Witnesses were describing these “hospital kidnappings” on social media. Last October, IRGC officers opened fire on a crowd of physicians in Tehran who were protesting these kinds of arrests, killing a young surgeon named Parisa Bahmani. Our location might also have provided a sense of refuge—on the seventh floor of a building on a busy boulevard, a 15-minute walk from the protests and high above the marauding police below.

We had two patients in the clinic—one who was already lying down for her lip injection. We quickly and quietly sent them home. The boy’s wounds had been inflicted by small crowd-control pellets, and my assistant readied the basic surgical tools we had on hand—forceps, scissors, gauze—to extract them. I could see the fear in the boy’s eyes, and I hoped he didn’t see the same in mine. I knew the situation could get critical fast. His blood pressure was low and his pulse barely detectable. Some of the fragments were buried in his flesh, and I knew I’d have to avoid pushing them in even deeper—it wouldn’t take much to penetrate the chest cavity. I was afraid of accidentally puncturing and depressurizing his lungs.

We gave him a saline IV drip to raise his blood pressure and injected him with lidocaine, a local anaesthetic, at the site of the injuries, where I had to dig further into his wounds to extract the shards. During the injections, he kicked against the procedure table, moaning in pain. It took more than two hours to remove two dozen fragments. When we finished, I wiped him down with antibacterial cream and told his father to keep watch for a fever caused by infection.

I never saw the boy again, but he was just the beginning. For the next two weeks, our small cosmetic clinic became an intermittent, ad hoc emergency room as anti-regime protests—and the ranks of the injured—kept growing. Along with other doctors in small practices nationwide, I established contact with the wounded through social media, friends and friends of friends. I knew I was making myself an enemy of the regime, that I was putting my life in danger. But after so much pain inflicted on my people, I was one of countless Iranians ready to take almost any chance for a better future.

***

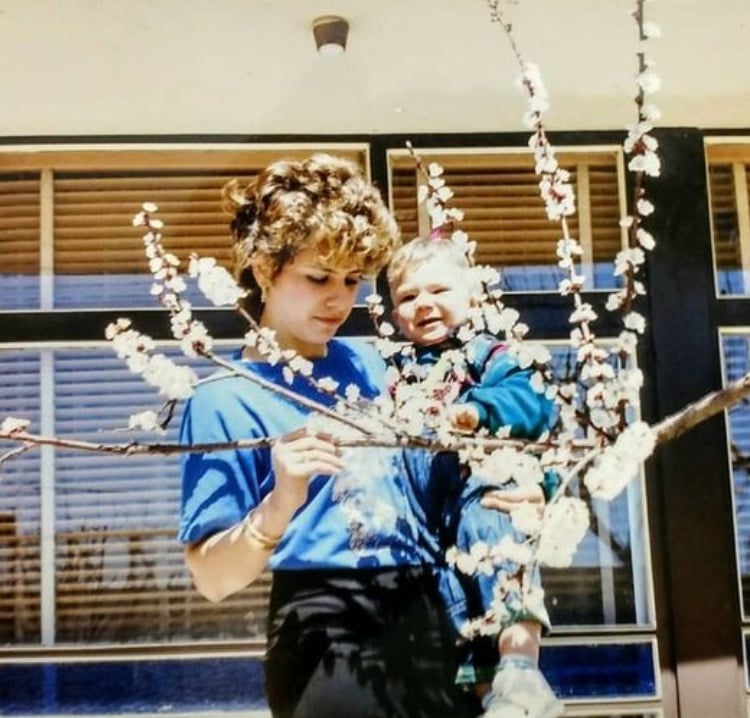

I was born in Gholhak, an upper-middle-class Tehran neighbourhood, in 1988. My father was an interior designer, and my mother was a singer and musician with an extraordinary talent on the piano and the tar, a traditional Iranian string instrument. I was their third and youngest child, and they named me Mohammadreza, after Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the deposed shah of Iran.

My namesake was the last ruler of the 53-year Pahlavi royal dynasty. During his reign, Iran was a constitutional monarchy, in which political power was heavily concentrated in the shah’s hands. But many Iranians nonetheless remember this time as a golden age, during which our rural, conservative society transformed into a sophisticated, urban one. The economy was booming, religious freedom was on the rise and women’s rights were expanding. All of this modernization, of course, was anathema to Iran’s most fundamentalist Islamic voices—including one of its clerics, the Ayatollah Khomeini.

In 1979, the ayatollah led a revolution to depose the shah. It didn’t begin as a strictly religious movement. Instead it brought together a variety of dissidents, including those on the left, who sought to overthrow the monarchy. Once the ayatollah came to power, he purged those other voices and imposed a brutal, repressive theocracy, with himself as head of state. Many Iranians, my family included, came to yearn for the comparatively enlightened, liberal years before the revolution. It was in this world of repression and nostalgia that I grew up.

The boy’s back was covered in blood, his shirt riddled with bullet holes. I felt my muscles tighten. “What happened?” I asked. But I already knew.

As a child and a teenager, I loved to draw, invent gadgets and devise new ways to solve problems. But my interests were scattershot, and it took a tragedy to focus my ambitions. When I was 12, a cousin of mine, nearly the same age, died after a years-long battle with cancer. He had planned to one day become a doctor and help find a cure for his disease. Years later, my mother helped me connect the dots between my still-raw heartbreak and my budding talents. “You have a good heart,” my mother told me when I was 16. “You can do the most to help people with your creativity and innovation as a doctor.”

I enrolled in medical school at age 20, planning to become a neurosurgeon. I was inspired by Madjid Samii, an Iranian who moved to Germany in the 1950s and became one of the most accomplished and revered neurosurgeons in the world.

In 2009, during my second year of university, enthusiasm began to build around the presidential election to be held that June. It was a small window of hope, half open, but it was more than we were used to. Iranian elections are usually little more than rigged contests, designed to legitimize candidates approved by the Islamic Republic’s supreme leader. That spring, opposition candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi began generating serious buzz, even stoking hopes of an upset. Iranians turned out in record numbers, with millions casting votes for Mousavi. But the election was rife with allegations of voter interference and vote-rigging, and when the government announced the results—only three hours after polls closed—the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was declared the winner with 62 per cent of the vote.

Hundreds of thousands of people staged protests that lasted for months, and dozens died at the hands of government forces. At the time, I was part of a student centre that operated as a campaign office for Mousavi. After the election, the university shut it down, and the senior students in charge were exiled to southeastern Iran. As a junior member, I was only suspended for a semester. But I was suspended again in 2013, after university security guards discovered that I’d spent time with a female classmate—Iranian law strictly limits interactions between unrelated men and women. We’d made a snowman together on campus and, on top of that unlawful interaction, I was accused of public nudity (I’d removed my jacket to dress the snowman).

A woman holds up her ponytail after cutting it off during a protest outside the Iranian consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, in September of 2022 (Photography by Yasin Akgul/Getty Images)

During my fourth year, my mother also felt the sting of the regime. She played regularly in a band—a mixed group of men and women—that rented out small performance venues in Tehran. One evening, they were performing in an event room on the top floor of a hospital. The audience was small, mostly friends and devoted fans. The regime already looked on this kind of event with suspicion, with its secular music and mingling of men and women. At one point, the band played Iran’s unofficial anthem, “Ey Iran,” a patriotic song dating back to the Second World War, which pays homage to the land, culture and history of the country—and is pointedly free of religious references. The regime can’t abide a celebration of Iran that isn’t also a celebration of Islamic fundamentalism, and singing this old song is considered a subtly subversive act. About 30 minutes later, plainclothes IRGC officers stormed the little room, cut the amplifiers and shut the entire thing down. We’re still not sure how they caught wind of it; we think a hospital security guard alerted them.

The IRGC forced my mother to sign a document stating she would never again act against the government. That night was the last time she ever played in public—a kind of death for a musician. For years afterwards, the memories were traumatic for her. She experienced something like PTSD, with flashbacks, weeping fits and bouts of arrhythmia from the stress of it all. My sisters had married and moved away, and she was alone. I began taking time off from university to be with her.

In time, I decided not to pursue neurosurgery. The time commitment was enormous: medical school, seven years of residency, then two years at the country’s neurological institute. Between my suspensions and caring for my mother—cooking, accompanying her on errands and to doctor appointments—I was already behind.

Late one night in 2018, during a hospital internship, I was making rounds to check on patients. I entered one room to find a young woman who hid her face as we spoke. She suffered from Bell’s palsy, which affected her facial symmetry. Her shame and sorrow over her condition left a deep impression on me. I told her there may be treatments for her condition, and that I’d like to return the next day to discuss them. By the time I did, she had already been discharged. It was then that I started to think seriously about becoming a cosmetic specialist. I finished medical school in 2020 and soon joined the cosmetic clinic, dividing my hours between Tehran, where I lived with my parents, and nearby Karaj.

I loved it. The work was a dream: financially rewarding and flexible enough that I could enjoy a rich personal and family life. We served wealthy Tehranis as well as clients with lesser means—in a country where women must cover nearly everything else, the face takes on an outsized importance. I even treated patients affected by Bell’s palsy, the same condition that affected the woman in that hospital room during my internship. In 2022 I was 33, with a tight circle of friends, a lively social life, trips to vacation villas and a budding career I’d spent years training for. Life was good.

One night last September, before the injured boy came to my clinic, I was at home after work, watching the satellite news. Most official news in Iran is simply regime propaganda, but millions of households use black-market satellite dishes to access international channels aimed at Iranians and broadcast from North America, Europe and the Middle East. I was watching Manoto, a U.K. channel, when the newscaster began telling Mahsa Amini’s story. I clenched my hands in rage. My older sisters had both had similar encounters with the Guidance Patrol when they were younger—pulled off the street and into vans, interrogated over unsuitable clothing, threatened, and accused of causing all the evils of the world with their loose morals.

Over the next week, as the uprisings swelled, the atmosphere in Tehran and Karaj grew tense. New protests popped up every day. In the evenings, when the staff and I left the clinic in Karaj, we saw a dramatic change in the neighbourhood. Shops and restaurants that used to stay open late into the night were closed, and the usually jubilant evening crowds were instead hurrying, heads down, to wherever they needed to be. Plainclothes IRGC officers, distinguished by pale shirts, loose pants and athletic shoes, clustered on street corners. They were pretending—unconvincingly—to be casual bystanders. In reality they were watching everything.

Even as the protests spread to every corner of the country, I remained unsure about my next move. “If you get taken away,” my mother said, “I will already be dead.” I promised I’d be cautious, as I considered how I could play a part in what I hoped would become a genuine revolution. Then the revolution came to me.

***

I hardly remember the drive home from work the night after we treated that first boy. I was enraged at the injury and cruelty.

I arrived home late and wrestled with whether I should become involved, and if so, what I could possibly do. But of course I was already a part of it. I’d chosen to become a doctor years before, and I couldn’t turn away when people needed me most. Before I went to bed that night, I posted a picture to my Instagram account, an image used by doctors across Iran to show their willingness to help people injured in clashes with regime forces. It was a simple illustration of a silhouetted doctor and two nurses, with a caption reading, “Count on me. I’m a doctor and I’m ready to help.” A little bit cryptic, but clear to those who needed it.

Mohammadreza and his mother at his grandfather’s house in the late ’80s

A pouch of soil from Pasargad, the burial site of Cyrus the Great—one of the few mementoes of home Mohammadreza was able to bring to Canada

During the next two weeks, we cancelled most of our regular appointments and turned the Karaj clinic into a makeshift emergency centre. Fortunately we already had the basics: oxygen tanks, resuscitation devices and a stock of staple medications and antibiotics. Our new patients found us one at a time—they were ex-clients, friends of my staff and family members, people removed by a few degrees of separation. Across the country, doctors in clinics large and small were doing the same.

In early October, a friend of a staff member came in with crowd-control projectiles lodged in his chest. He’d tried to remove them at home, but instead pushed some in deeper, where one had become infected. By the look of the infection, the wounds were probably about a week old, and though he’d already found antibiotics, he needed the pellets removed—he feared going to the hospital, where people were being arrested, then subsequently tortured and raped.

A few days later a teenage girl came in heaving, her eyes wide with panic, choking with each breath. She could hardly speak, and her skin was a sickly pale colour. She told me she’d been exposed the previous day to tear gas seeping through her apartment windows. The story sounded implausible to me—her symptoms seemed much too severe for such casual exposure. But I couldn’t blame her if she was using a cover story to hide her attendance at a protest. It was also hard to believe she’d only been exposed to tear gas, rather than something much worse, like chlorine gas. She was wheezing and nauseated, her heartbeat was over 100 beats per minute and her oxygen levels were low. Tear gas doesn’t produce those kinds of symptoms, and certainly not a full day later. I placed an oxygen mask over her face to help her breathing. I gave her saline to raise her blood pressure, corticosteroids for her breathing, benzodiazepine for anxiety, and anti-nausea medication. Soon she fell asleep. She woke half an hour later, flush with colour and breathing normally. I remembered what my mother had told me about becoming a doctor, about using my abilities to help others. It was an incredible moment, a rush of pure joy. Nothing in the world could match the feeling I had. This was why I’d become a doctor.

I wrote her a prescription for an inhaler using the name of my secretary’s asthmatic father, since a prescription like that for someone without a history of asthma might arouse suspicion. My secretary herself picked it up.

Soon, I was receiving requests to treat people in their own homes or in safe houses where they’d holed up. These were far more dangerous, requiring travel throughout Tehran and Karaj, past protest zones and police checkpoints. I got the first call for a house visit while eating with a friend at a pizzeria. A woman’s voice said, “You remember those dark spots on my skin you removed? My friend’s son has the same; can you look at him?”

I was baffled—what spots? Who was this? Then I recognized the voice as someone I knew, and the subterfuge clicked. I began driving to the address she gave me, until she called back: don’t bother. Police had raided the home and taken the boy away. I deleted the address immediately from my phone. Police had begun searching citizens’ cell phones at checkpoints.

I made—or at least attempted—10 house calls in the next two weeks. One of the first was in Punak, a neighbourhood in Tehran, to treat a man who’d been shot in the chest with crowd-control projectiles. The address I needed to reach was on the other side of an expressway, and the only road access was through a major crossroads called Punak Square. As I approached, I could see and hear crowds of protesters from blocks away. Traffic was already snarled to a standstill. As I pulled over to consider my next move, 30 or 40 motorcycles roared by—each had two riders mounted on it, some brandishing guns, others an arsenal of medieval-looking weapons: stakes, machetes, chains, blunt objects. They wove their way through the traffic jam, shouting, swearing and revving their engines, scattering the protesters and taking control of the square.

It’s hard to know who these people were, but everything about them bore the hallmarks of the lebas shakhsi—plainclothes goons, widely believed to be affiliated with the IRGC, their members often drawn from the ranks of violent criminals.

There was one other route, a small pedestrian bridge a few blocks north of Punak Square that I could use to cross the expressway and enter the neighbourhood on foot. I parked my car, gathered my instruments and set out. But when I got close, I could see the Basij militia at the other end of the bridge. I had to retreat and call the patients from my car, administering help as best I could over the phone.

Another house call, in early October, was at a friend’s home in Sattarkhan, a bustling, densely packed neighbourhood in western Tehran, close to major protest sites including Sharif University and Sadeghieh Square. It was just after sunset as I drove into the neighbourhood, and I found the streets full of people and cars, horns blaring ceaselessly and deafeningly. From streets, rooftops and windows came the cries: “Death to the dictator, don’t be afraid, we are all together!” Closer to the square, police vehicles were parked by the roadside. As I passed, officers looked me in the eye, sizing me up. A few hundred metres down, protesters were huddled around fires lit in rubbish bins.

Dozens of motorcycles roared by, their riders brandishing an arsenal of guns and medieval-looking weapons: stakes, machetes, chains, blunt objects. They wove into the traffic jam and took over the square.

I wove into a narrow alley toward my friend’s first-floor apartment. Inside was a woman in her 20s. Her arms, shoulders, face and back were covered in deep purple bruises. Injuries from a police baton or the butt of a gun, my friend said. The woman had a crushing headache, a likely sign of concussion, but there was little I could do besides diagnose her. She eventually decided to go to a hospital, despite the risk. She needed her injuries assessed in case it was something worse than a concussion—a skull fracture, or bleeding on the brain. I waited in the apartment with my friend until 4 a.m., but the woman never returned.

I drove home through streets cluttered with broken stones and discarded waste bins. The tire fires protesters lit hours before had died, but the pungent, toxic smoke was still drifting in the air. When I reached the highway the air cleared, and the chaos fell away. For a few minutes, I felt almost normal. I got home and closed the door, and after a few moments noticed a dull, throbbing pain in my palms. I had gripped them so tightly on the steering wheel I’d bruised my own hands.

I never spoke to my friend again, nor learned what happened to that woman with the concussion. Even a phone call to find out would have been too dangerous.

In early October, I got a text message from an unlisted number, asking me to come to a particular address for questioning. Another friend of mine, also a doctor, had received a similar message a few days prior. He had gone and never returned. I ignored the message. A week later, my secretary called me from her private cell phone. She sounded nervous, and asked if I’d made an appointment with two large, tough-looking men: “They insist that you’ve personally booked with them.” I told her I wouldn’t be in that day, and they should return on Saturday.

I don’t know what happened after I hung up. I don’t know if they left quietly or peacefully. I can only pray they did. I never spoke to my secretary again. That was the moment I knew my life in Iran was over.

***

I went straight home and dug a small backpack out of the closet. I packed a few changes of clothes, my medical school papers and a visitor visa to Canada I’d never used. I’d gotten it for a conference in Vancouver months prior, but hadn’t gone due to a scheduling conflict. Now it saved me.

I took my guitar—a graduation gift from my mother—and a small plastic pouch that I’d carried with me for years. It contains a few pinches of soil taken from Pasargad, the site in southern Iran where Cyrus the Great, the founder of the first Persian empire, is buried. Years before, I’d asked a friend of mine who was visiting the area to pick it up. She was a little perplexed by the request, but to me, the figure of Cyrus, and the landscape of Pasargad, symbolized so much of what was great about my nation: its glorious history, its beautiful landscapes, its extraordinary people. Now this tiny piece of home would be with me in exile.

I was blessed with few goodbyes; both my sisters live in Europe with their husbands. My parents drove me to the airport, and my father and I both cried. We had no idea when we’d see each other again.

The airport was crammed, and when I approached the gate to board the flight, the border officer asked me to wait. He took my passport into another room, emerging minutes later to tell me I was missing a necessary stamp. “You can’t leave,” he said. I begged, tried to convince him that I was needed on an urgent professional trip. Another man arrived and said their computer system was down, and I would have to wait until it was repaired before they could do anything more.

I waited for half an hour at a self-serve counter in the business lounge, eating tomato soup and gheymeh, an Iranian dish of meat and rice. Eventually the officer waved me back. He told me to fill out a long, detailed form about my previous travel and attest that I was leaving on a work trip. He asked for my home and work addresses, and made me sign my name more than a dozen times, attesting to various details, before finally pressing my finger into an inkpad. I printed it on the document everywhere I had signed my name.

The IRGC have been to my parents’ house. They know I’ve left, and I expect they’ll keep harassing my family. I’m afraid for them and for my country. But I’m hopeful as well.

I flew first to Istanbul, lying low at a friend’s house for five days while waiting for a cheap, direct flight to Canada. Turkey is full of Iranian espionage agents; I felt barely safer there than I had in Tehran. After I finally boarded the plane to Toronto, I spent the flight in something close to disbelief. When the wheels skidded onto the runway at Pearson airport, my only thought was, I’m alive.

In my first months in Canada, I stayed in Airbnbs in Vancouver and Toronto, living as cheaply as possible. I only brought $5,000 from Iran, and the money didn’t go far. I’m currently staying near Toronto. An immigration lawyer has taken my case and filed for refugee status on my behalf.

I spend my days walking—it’s free, and it gets me out in the sunshine and fresh air. I save money by cooking for myself; sometimes I’ll treat myself to an apple pie and coffee at McDonald’s, where I take advantage of the Wi-Fi.

In Iran, I was successful, happy in my job and living with a family who loved me. In Canada, I’m jobless and nearly penniless, trying to start over from zero. But I don’t regret what I did: my name will now stand alongside all those others who fought. The night that boy and his father found me, I discovered my role in the world, forging a better future for my nation. Since I left, I’ve been following the news from Iran every day, every hour. I haven’t been able to contact colleagues or friends, and I’ve only spoken to my parents briefly. I don’t know what will come next. I hope to work again as a doctor here in Canada.

Whatever happens, I can’t go back to Iran—not now, and maybe never. The IRGC have been to my parents’ house. They know I’ve left, and I expect they’ll keep harassing my family. I’m afraid for them and for my country, but I’m hopeful as well. There are times when I think I should have stayed to fight, especially when I see the Iranians who are suffering and dying at the regime’s hands, their incredible bravery an example to us all.

Iranians are peaceful people. But we’re out of patience. We’ve allowed lunatics to lead us, and we’ve paid the price for four decades. It’s no longer a protest in Iran; it’s a revolution. It’s not only about women’s rights, nor is it limited, as regime propagandists have declared, to unruly young people or to just a few parts of the country. It’s an entire nation fighting for its values, history and freedom, and for a modern, secular and democratic political system. When these dark clouds pass, a bright sun will shine upon Iran and the world will see its real face: gorgeous, peaceful, rich and thriving.

— As told to Maria Calleja

This article appears in print in the February 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.