The rise and fall of WE

The charity invented by an earnest 12-year-old finds itself engulfed in a cynical, star-studded cronyism scandal. How on earth did we get here?

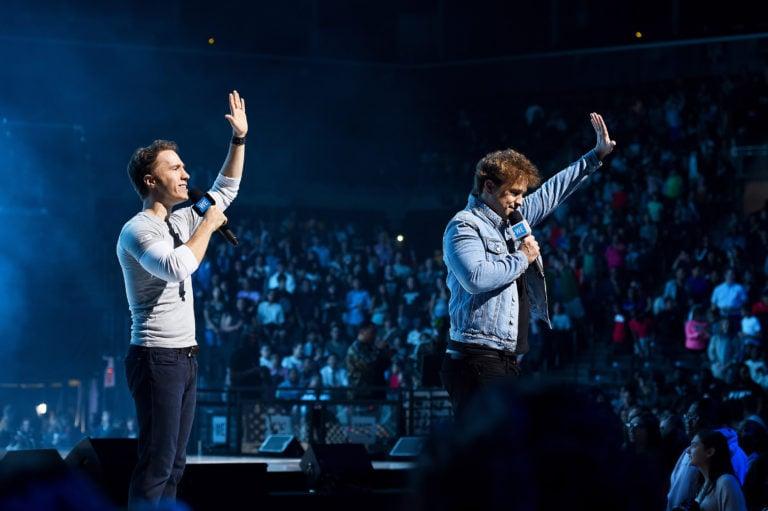

Craig (left) and Marc speak to thousands during WE Day UN in New York City last fall (Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images)

Share

This article appears in print in the October 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “From WE to they.” On Sept. 9, 2020, WE Charity confirmed it will be shutting down its Canadian operations and the Kielburgers will step down.

An adolescent boy in a blue T-shirt, hosting a press conference on his first trip abroad, is sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with an Indian girl as she reads from a piece of paper. In front of Canadian reporters, the girl implores the Indian government to address the practice of child labour.

The boy, Craig Kielburger, needs no notes. With what a travelling Maclean’s reporter then described as “the poised assurance of a veteran performer,” young Craig demands a meeting with prime minister Jean Chrétien to discuss the issue.

“Forget being prime minister for a second. Just simply as a Canadian, it’s his moral responsibility to do this,” he insists. The two meet for 15 minutes five days later, in January 1996, and though Craig complains to reporters that Chrétien’s commitment to child labourers is “vague,” the appointment itself is an out-and-out victory for a growing movement of impassioned Canadian youth.

Fast-forward nearly two decades. Onstage in front of 16,000 youth who have earned their tickets through service and fundraising, Craig Kielburger is elated. Wearing a blazer-and-jeans combo that matches his older brother Marc’s, he hypes up the crowd. “We are honoured to welcome to the stage two individuals who are passionate about young people, bettering their community and the world.”

For one of the guests, it is a “first public appearance” since being sworn in less than a week ago, Marc exclaims. “How cool is that?” The fresh-faced crowd goes wild. The guest, Marc tells them, “truly believes in the power of young people” and “truly believes in you.”

As Justin Trudeau and his wife, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, appear on stage, a hot microphone catches Craig making a joke about “campaign rallies” as he hugs the newly elected Prime Minister.

In his brief remarks, Trudeau, with rolled-up shirt sleeves, sums up the nebulous mission of the charity’s modern-day iteration. “WE Day is about showing you that ‘we’ is powerful, that ‘me’ as part of ‘we’ is powerful, and that together we can and will change the world.”

The contrast between the two images is stark. In the former, a young boy rails against the vague assurances of one Canadian prime minister, demanding he back up his empathetic signals with action; in the latter, that boy-turned-seasoned-charity-mogul embraces the platitudes of another PM, seemingly secure in his belief that this is the best way to change the world.

Craig learned early about the intersection of power, youth and influence. The charitable behemoth now known as WE was propelled by smart fundraising and the dedication of young do-gooders, to be sure, but also by successful solicitation of powerful politicians and corporate interests.

Headed by an activist wunderkind—Greta Thunberg is not the first—and fuelled by celebrity, the Kielburgers’ growing organization sought to go beyond freeing foreign children from bondage. Today it defies easy description, from its high school clubs to international development projects to ethical chocolate sales to mental health advocacy. From simple beginnings, it twisted off in umpteen well-intentioned directions until, for better or worse, its brand became synonymous with good intentions themselves.

Their aura of positivity and stadium rallying cries made the Kielburgers and Trudeau’s sunny-ways Liberals perfect dance partners. But instead of vaulting the organization to new heights, a hastily conceived pandemic-era partnership exposed, for WE and the Trudeau government both, the perils of acting with virtuous conviction, absent second thought.

Scrutiny of the dead-on-arrival Canada Student Service Grant (CSSG) program led to a conflict-of-interest investigation for Trudeau. The Kielburger undoing may be bigger yet as corporate donors abandon the cause, school boards rethink their ties and critics call for the brothers to cede control.

***

It is an origin story told countless times: 12-year-old Craig Kielburger was at home in Thornhill, Ont., ready to flip to the comics section of the Toronto Star on an April morning in 1995. Then he saw a front-page article about a Pakistani child labourer turned activist who’d been killed.

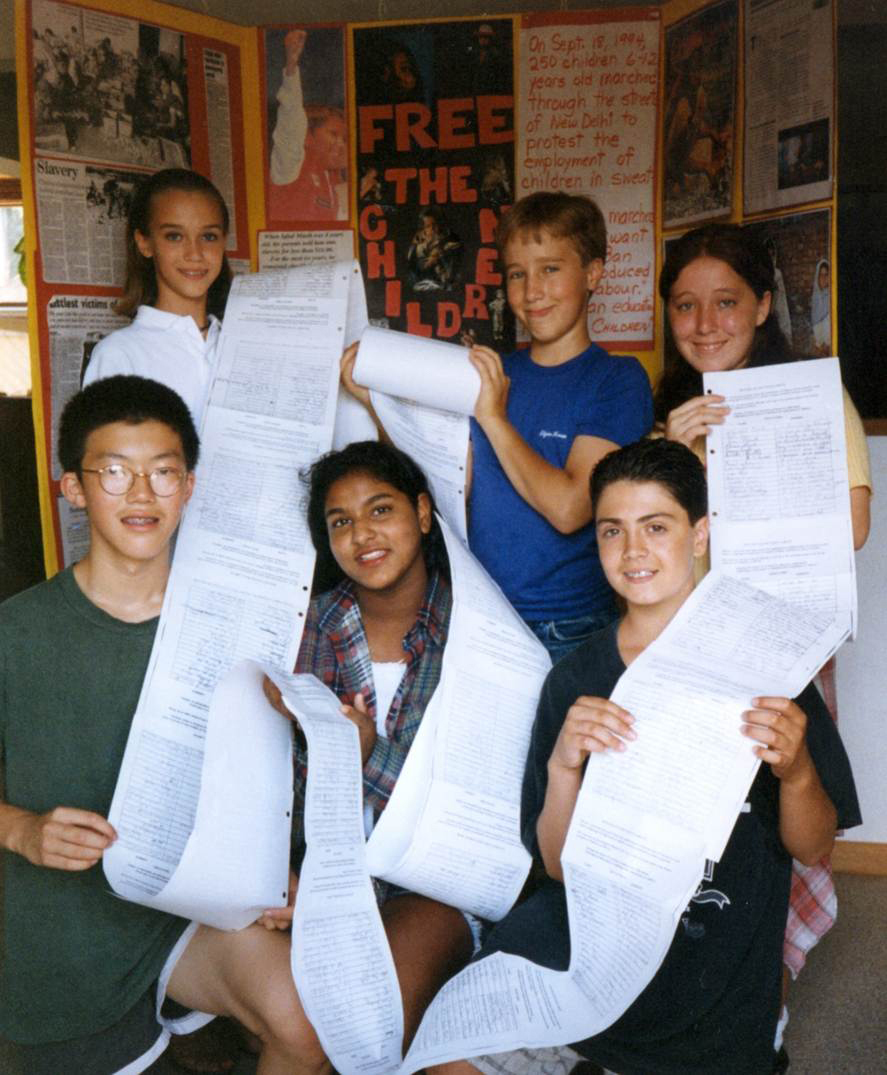

He told his Grade 7 class about the death of Iqbal Masih and asked if anyone wanted to start a group to carry on Masih’s mission. “We were all asked to write an essay on why we would want to be involved,” recalls Ashley Stetts in an email. She joined the group before they even settled on a name: Free the Children.

In the early months, there were petitions to foreign leaders and speeches at nearby schools. Despite its members’ youth, or because of it, the group found a growing audience. Reaching powerful ears was soon a priority. Garage-sale fundraisers were quickly overshadowed by the windfall of $150,000 in donations that came after Craig’s speech at an Ontario Federation of Labour convention.

'It wasn’t necessarily an organized effort with a clear goal. We were 13.'

Late in 1995, Craig embarked on the seven-week trip to South Asia that would see him connect with Chrétien. He came home to a hero’s welcome and attention outside Canada. He appeared before U.S. congressional committees, met with vice-president Al Gore and was the subject of a glowing profile on the popular U.S. news broadcast 60 Minutes.

Supporters popped up south of the border. “We shared a similar mission and passion related to child labour,” says Shannon Goold, who started a Free the Children chapter in Washington. “But it wasn’t necessarily an organized effort with a clear goal. We were 13.”

If there was an obvious goal, aside from spreading awareness, Craig articulated it on C-em in 1996: “The eventual elimination of child labour and the exploitation of children.” He said youth could do more than just play video games or hang out at malls, “which the media portray as young people’s role.”

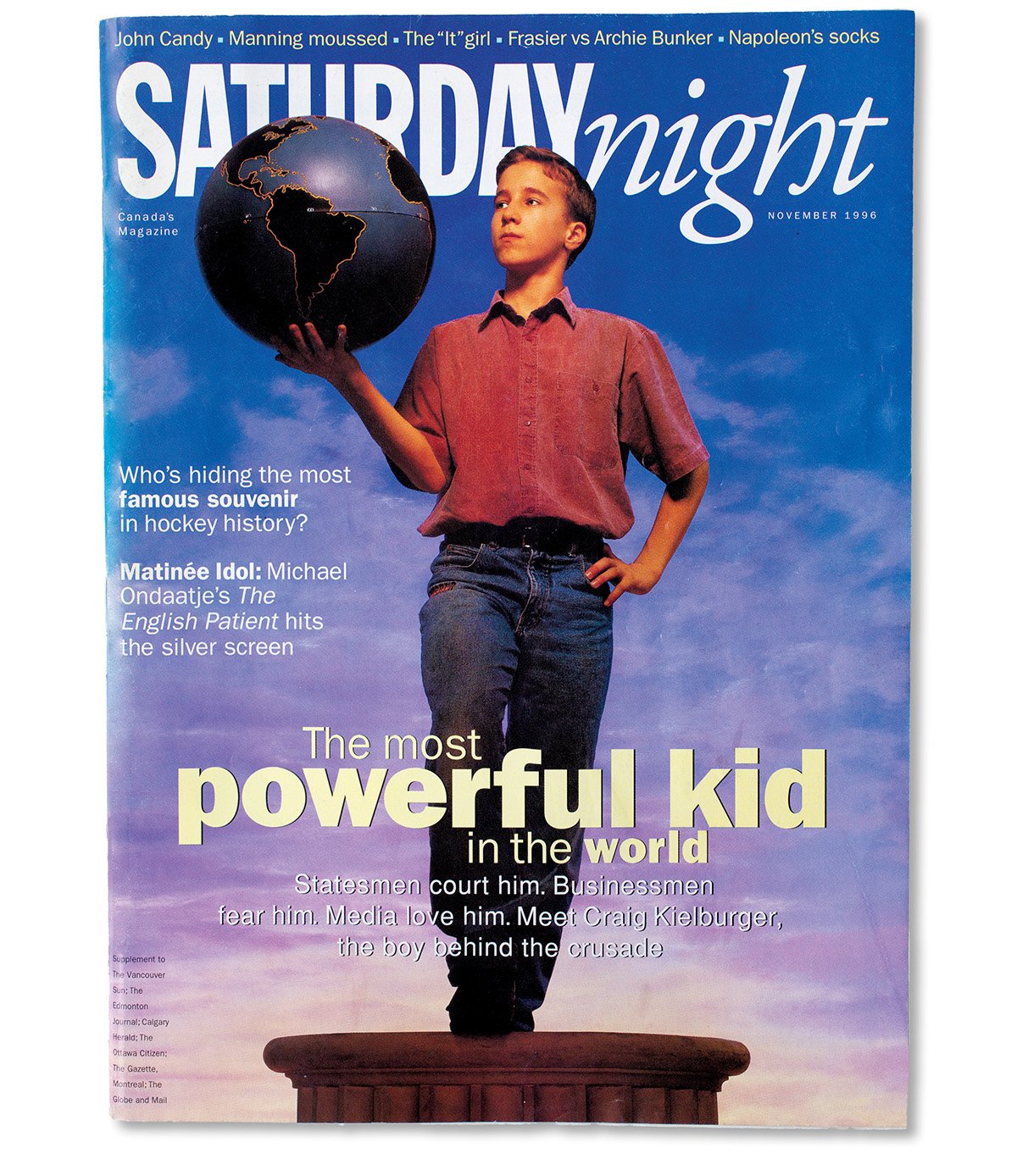

With more attention came more critical scrutiny, which wasn’t always welcome. In a 1996 profile of Craig in the now-defunct Saturday Night magazine, the writer describes taking notes as Craig tells an anecdote about he and Marc gathering stranded baby frogs in buckets to move them to a pond. Craig interjects, asking the journalist not to include the story: “It’s not part of the image I want to convey.”

Craig had bigger problems with the article, titled “The most powerful 13-year-old in the world.” He sued the magazine for libel, not just because it alleged his family was financially benefiting from the not-yet-registered-charity Free the Children, which he strongly denied, but because of its general tone, depicting him as a “precocious pubescent” who had “learned to speak in almost perfect sound bites.” He eventually got a $319,000 settlement from the magazine.

Until 1997, Free the Children was essentially a club. That year, two legal entities were born to cover its activities. Kids Can Free the Children was a registered charity fundraising for international development work, while Advocates for Free the Children was a non-profit organization that, unlike a charity, was allowed to spend more than 10 per cent of its time on “advocacy,” petitioning Canadian governments on issues such as the politics of child labour. By 1998, Free the Children had paid employees. The Advocates non-profit gradually became a smaller part of activities and eventually ceased to exist.

RELATED: Every important number in the WE drama that’s consuming Ottawa

If the meeting with Jean Chrétien and the appearance on 60 Minutes were breakthroughs, they were dwarfed in 1999 by Craig’s appearance on the Oprah Winfrey Show. It became clear that Free the Children was expanding well beyond child labour issues. Oprah announced that she wanted to help Craig build 100 schools abroad. The charity would have its work cut out for it.

The Kielburger parents eventually moved out of their family home and the charity took it over, says Kim Plewes, then a volunteer and now a senior adviser with WE. Some workers moved into the upstairs bedrooms. The house got full enough that others opted to pitch a tent in the backyard. “It was about the impact we were all coming together to create,” Plewes says, “and we were all willing to make certain sacrifices at that age.”

The same year, Marc co-founded a private company, Leaders Today, a precursor to what would later be rebranded as ME to WE. A funding vehicle for Free the Children, the for-profit entity offered products and services that couldn’t get the green light under Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) charity regulations. Along with organizing overseas volunteering trips, it provided “training for college applications and maintaining scholarships.” Marc explained in a 2007 interview: “We run the place with a non-profit philosophy but with business principles.”

Leaders Today dabbled early in the concept of giving kids a feel-good experience when they travelled abroad—and when they raised money at home. A “FUNdraising Pack” encouraged would-be trip-goers to brainstorm names of those who might be willing to help financially. Each would be rated from one to three. A “one” might give $75, $100 or more. A “three” would chip in, say, $2, no more than $10.

Free the Children volunteers would relay first-hand accounts of journeys abroad during talks to schoolchildren in Canada. The trips were always in “demand,” according to a former paid staff member who went to Thailand, Kenya and Nicaragua. He is one of several ex-volunteers and staffers who spoke to Maclean’s under condition of anonymity—in some cases out of concern their current employers would disapprove of them commenting; in others, out of fear they would be violating non-disclosure agreements. (Maclean’s requested an interview with the Kielburger brothers; they provided a written statement.)

Craig's first trip to Southeast Asia in 1996 (Courtesy of WE)

A trip abroad cost $5,000 per person, remembers one Leaders Today participant. She canvassed stores in her neighbourhood to fund her two-week trip to Thailand in the early 2000s. There, she and others slept on mattresses in a large communal space, within a community she described as a “slum”—the area did not feel unsafe, she says, but it was littered with garbage. Participants helped Thai kids with English lessons at a local school, took part in cultural activities and cooked Thai food, then spent a week on an island doing “leadership training.” She says she doesn’t remember any talk about child labour.

The participant’s description of spending time in a more impoverished part of the country contrasts with Craig’s own description of Bangkok, its capital. In his 1999 book, Free the Children, he lamented that the city, in its modernity, had “given itself over to Western influences, to commercialization in its most vulgar form.” By the same token, he praised Mother Teresa, whom he had managed to meet with during his first trip to India, for her simple living and lack of ego.

In a similar vein, the charity posted a youth declaration on its website in 2003: “Globalization, without proper guidance and management, leads to the untrammelled pursuit of profits, often at the expense of social justice.”

By the time Craig turned 21, Free the Children reported it had recruited 300,000 active members in 35 countries, built 300 schools (of which Oprah helped build about 60, according to her website), provided daily education to more than 15,000 children, established rehabilitation centres in India for freed child labourers, and sent millions of dollars of medical equipment overseas.

As the kids in charge grew into adults, their vision for the future of the organization began to shift. An initial focus on child labour evolved into a broader focus on international development. Now, the experience of Canadian participants—always a major concern—began to take on outsize importance; the symbolic rejection of commercial interests, less so.

In its early years, the charity fostered a culture where staff felt comfortable lobbying against taking money from a major U.S. bank, according to the former staffer, because of the “bad trend” that could set. Plewes, for her part, remembers that in the early 2000s, there were deliberately no brand campaigns, celebrity engagements or splashy galas.

In 2004, a new staff member—Russ McLeod, now executive director of ME to WE—came up with the idea for a sponsored, rally-style event to reward Canadian volunteers. The idea was met with skepticism, but within a few years would become a “central pillar to the organization,” as Plewes puts it.

“I thought, ‘You’ve found the wrong organization, man. This is not what we do,’ ” she says of her initial reaction. “That was my mistake, as opposed to saying, ‘What a brilliant, new, innovative idea. Let’s become an organization that does that.’ ”

***

When the tsunami ravaged Southeast Asia in 2004, the Kielburgers’ charity rushed in, because that’s where need—and public attention, and donor dollars—had shifted.

They urged student supporters to raise funds for new Sri Lanka aid projects, and secured funds from Oprah Winfrey’s Angel Network. Money flowed to tsunami relief, but shrivelled up for other charitable causes, worrying Free the Children leaders. They began wondering, they’ve said, about different, sustainable revenue streams.

In 2005, Marc chewed this over at lunch with former Harvard classmate Oliver Madison, a private banker. Late that year, the brothers launched the for-profit company ME to WE Style, with Madison as CEO. They marketed eco-friendly, ethically produced sweatpants and T-shirts at a time when “eco-” and “ethical” were huge buzzwords. The added incentive: half of net profits went to Free the Children.

It was a ragtag operation. One early staffer recalls getting a fresh copy of a Kielburger book, promotional videos and a laptop, and being instructed to start immediately. That book was 2004’s ME to WE: Finding Meaning in a Material World, which touted a self-help philosophy of finding fulfillment in helping others. The mindset found root in the clothing company—“If you knew that your T-shirt could change the world, wouldn’t you want to fill your closet with style that matters?” one promotion read. ME to WE volunteer clubs sprang up in schools; the organization’s guest speakers inspired; fledgling curriculum programs ensued. Many volunteers became employees, but the charity’s ambitions strained young staff. Several ex-employees describe experiencing burnout. One former full-time speaker says a schedule of 14-hour days, expectations to be in the office on days off and pressure from management to reach lofty sign-up and fundraising goals left her struggling with depression. “I had to give motivational speeches while feeling that way.”

Craig appearing on Oprah Winfrey’s show in 1999 (Courtesy of WE)

The Kielburger brothers and the Dalai Lama in 2009 (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

***

In 2007, the charity filled a Toronto arena with enthusiastic middle- and high-schoolers for the first “ME to WE Day” (later WE Day), led by Russ McLeod, who after several years had succeeded in getting his idea off the ground. The event marked a turning point for the organization as the Kielburgers began to invest in the idea that doing good should feel good.

Speakers included the cast of Degrassi, retired general Roméo Dallaire, the Kielburger pair and Justin Trudeau, via video message: “We don’t need you to be leaders of tomorrow,” the soon-to-be Liberal MP said. “The only way to make a difference tomorrow is to start today.” The event also showcased the charity’s increased ability to draw sponsors: Telus, National Bank, eBay and more.

Despite the high-calibre celebrity and corporate lineup, the Kielburgers’ staff ran and organized nearly everything for early WE Days. In gruelling, 16-hour-plus days (which the charity says would “not be normal business practice” now), workers oversaw parking and crowd-wrangling, and supervised the school groups that came early to stuff participants’ swag bags with giveaways and promotional brochures.

The arena days became more professionally run as they grew. ME to WE Style was there with concert-merch-style booths, routinely selling 5,000 shirts per event. For a $40 shirt, “we realized these kids are thinking $20 is going back to Free the Children, not understanding the verbiage [about net profit only],” the former Style employee says.

In 2008, the Kielburgers incorporated and launched ME to WE Social Enterprise, a for-profit company that subsumed ME to WE Style, the Leaders Today trips and training, and some short-lived product lines. “Traditional philanthropy wasn’t connecting with the next generation, so we tried fashion, books and music to engage youth to care about causes,” says the charity’s present-day chief operations officer, Scott Baker. “Unfortunately, the necessity to create these entities is often portrayed as suspicious, when in fact it is an innovative and entrepreneurial approach to operating within Canada’s antiquated and constrained regulatory environment.”

This company, too, pledged to pump half its net profit into the Kielburgers’ charity, the other half going back into the enterprise (in more recent years, says Baker, 90 per cent of profits have gone to the charity). The company encouraged youth to live and consume according to the ME to WE ethos. “It’s not just about people using their paycheques and putting in volunteer hours for charity,” Craig told a reporter in 2009. “It’s about thinking about the trips they take, how they learn, how they shop and how they interact with the world on a daily basis.”

National Me To We Day in Toronto in 2007 (Ron Bull/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

While this was novel in Canada, where charities’ for-profit activities are heavily regulated, there were international examples: Bono’s (RED)-branded products supported the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, and Oxfam opened U.K. stores full of housewares and gifts.

Roxanne Joyal, Marc’s wife and CEO of the ME to WE company, launched a line of accessories made by a group of artisans in rural Kenya—the Rafiki beaded bracelet became a signature item. In addition to setting up supply partnerships with stores, the enterprise launched various licensing deals: with Staples and Hilroy for specially branded school supplies, and with both Lipton Tea and David’s Tea (the latter was served at Craig’s wedding, where Rafikis were a party favour). On the charity side, there was even a Free the Children RBC Virtual Visa Debit card aimed at young shoppers.

More recent products include the ambitiously named Chocolate to Change the World and Coffee to Change the World; this year, the WE organization registered a trademark for ME to WE Impact Points, a proposed credit/debit card rewards program. Sales of items such as bracelets and chocolate have created jobs for some 1,800 artisans and farmers abroad, the organization says.

Along with the business ventures, domestic youth programs grew rapidly. One-year programs to encourage students’ support for charitable causes—not just WE Charity itself—became known as WE Schools, with cross-Canada provincial funding and free curriculum modules, underwritten by sponsors and donors named on teaching materials. By 2010, they boasted reach into 4,000 schools. Before the decade’s end, that would quadruple to 16,000 schools, attended by 4.3 million students in North America and the U.K.

Craig (left) and Marc speak at a WE Day (Hannah Yoon/CP)

The charity stresses that neither money raised by schools nor donations for international development are used to pay for WE Schools or WE Days. It estimates that in 2018-19, WE Schools produced some US$321 million worth of “impact value,” that is: the combined value of students’ hours of service, food donations and dollars raised for causes (WE Charity itself only received about 22 per cent of funds raised at WE Schools between 2014 and 2018, it says).

The Kielburgers and WE enjoyed huge success in parts of the U.S., especially in liberal states like Washington, New York, California and Minnesota. Schools embraced free curricula; kids enjoyed the WE Day celebration; and major sponsors such as Allstate Insurance, Walgreens and Microsoft welcomed exposure with the broadly idealistic movement.

“It was a pretty safe bet—you’re not supporting a cause; you’re supporting getting kids involved in causes,” says David Stillman, former U.S. director for WE. American celebrities including Magic Johnson, the Jonas Brothers and Natalie Portman backed the movement. On one ABC-broadcast WE Day—in 2015, the same year the Kielburgers welcomed a newly elected Trudeau to the stage—then-first lady Michelle Obama praised students “for showing the world that ‘we’ is so much stronger than ‘me.’ ”

Craig, Grégoire Trudeau, the PM and Marc onstage for a WE Day in Ottawa in 2015 (Chris Wattie/Reuters)

In 2016, Free the Children became WE Charity. Somewhere along the way, entities went all-caps, no longer simply “Me to We.” As it shifted toward a focus on youth engagement and away from humanitarian work, the organization became part of the burgeoning “happiness movement,” says David Jefferess, a cultural studies professor at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus. “What they want to do is play on this idea that Canadian youth have an unfulfilling life,” he says. “And the way to be fulfilled is to associate with WE. So it becomes about the brand.”

WE Charity counters by citing intangible benefits: according to a social-impact measurement firm it hired, the school and WE Day programs make youth more likely to vote or start a non-profit than their peers.

The branded products did produce profit that the ME to WE company rendered to the charity. ME to WE has contributed more than $20 million to the charity since 2009, the group has repeatedly said, though some of that took the form of in-kind services like administrative help, office space or support for WE Day. That $20 million is less than five per cent of the charity’s overall revenue in the past decade, according to financial statements. Money flowed in the other direction, too. The charity purchased at least $11.6 million of supplies and services from the ME to WE business, disclosures show.

At least $126 million has come from other “corporate partners,” the charity’s annual reports state. And few charities can boast the depth and breadth of corporate sponsorship that WE does—or the ability to draw celebrities, or the appeal to politicians.

When the Kielburgers made their first public appeal weeks after the 2004 tsunami, Ontario’s then-premier Dalton McGuinty appeared with them. Public document disclosures reveal letters from the brothers to former B.C. premier Christy Clark over several years of her tenure, in which they lay out the benefits of the province’s annual $200,000 grant for their organization’s education programming. They also invited Clark to speak at annual WE Days, to attend a celebrity-studded donor function at a local developer’s mansion and to join a school-building trip to Kenya, which Clark planned to do with her son in 2013 before cancelling last-minute.

In July 2015, Craig’s WE Day invitation letter to Clark added: “We would like to humbly request that the province of British Columbia’s support be renewed once again with a continued investment of $200,000 for the 2015-16 academic year.” (WE Charity says a formal proposal was also sent by Vancouver staff.) Clark’s government obliged, announcing the funds on the day the premier shared the WE Day arena stage with Henry Winkler, Marlee Matlin, Barenaked Ladies and others. In its statement, WE Charity says this was an informal reference to funding separate from its formal request to the ministry, and that it invites leaders of all political stripes with no funding strings attached.

***

As an enterprise that had come to rely so heavily on travel, retail and events, ME to WE would have been hurt by the global pandemic and economic crisis no matter what.

“The pandemic has been devastating for the organization,” Russ McLeod, the executive director of the ME to WE company, says in an interview. There is no travel. There is a significant threat to retail. Beading workshops in Africa shut down. “Prior to the pandemic, we were probably 135 full- and part-time employees. Today, we’re maybe six.”

At WE Charity, meanwhile, 203 employees were let go in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown, its statement says. Former board chair Michelle Douglas, in testimony to Parliament, said Marc asked her to resign at the end of March after her repeated demands that the board be provided with better financial documentation to justify the layoffs. “There was a difference of opinion between Ms. Douglas and WE Charity senior management regarding pandemic staff terminations. It was a trying time for everyone, and the outcome was regrettable,” says Scott Baker, the WE Charity chief operations officer. After “staffing transitions” and pivoting to virtual delivery of school programs, WE Charity itself was in “stable financial standing,” he says.

The Kielburgers have strongly denied that WE stood to make any profit from working with government. But it was during this “trying time” in April that a seemingly golden opportunity presented itself.

The charity had received federal funding for programs prior to and since Trudeau’s election—to the tune of $5.5 million since 2015, including money for a special Canada 150 WE Day. Though it hadn’t registered any lobbyists—a normal practice for Canadian charities—WE staff were frequently in touch with government officials. (Rules stipulate that “lobbyists” need only register if they spend more than 20 per cent of their time on lobbying activities.)

Early in April, WE Charity pitched the feds on a social entrepreneurship program. Craig picked up the phone to discuss it with Small Business Minister Mary Ng and later with Youth Minister Bardish Chagger, who had taken over the “youth ministry” from Trudeau himself after the last election. Craig also directly contacted then-finance minister Bill Morneau about the program, in one of several April emails he addressed to “Bill,” records submitted to a parliamentary committee show.

RELATED: The obvious lessons Justin Trudeau keeps failing to learn

But faced with a crunch of unemployment that was putting students in dire financial straits, ministers wanted to think bigger. As the COVID-19 cabinet committee discussed a wider volunteering program, disclosed emails suggest Chagger offered to connect the Kielburgers with civil servants, who asked the charity for a new proposal.

On April 22, Trudeau formally announced the up-to-$912-million Canada Student Service Grant program. The same day, Craig sent a revised proposal. A month later, Trudeau’s cabinet signed off on a grant program worth $543 million, for which the public service had decided—in their rush to provide advice on a perilously truncated timeline—that WE could be the only administrator. Some $500 million in grants tied to volunteer hours would have been available to students, while up to $43 million could be expensed by WE for its costs.

The partnership quickly unravelled. It was not lost on Trudeau’s political opposition, nor on the media, that the Prime Minister had spoken at six WE Day events, that his wife was hosting a podcast for the charity and that she had, weeks before Trudeau announced the program, been photographed with actor Idris Elba at a WE Day event in London, U.K. (Both were diagnosed with COVID-19 shortly after the early March event.) The WE organization confirmed it covered Grégoire Trudeau’s expenses for the trip—something that Trudeau’s chief of staff, Katie Telford, testified was approved by the federal ethics commissioner, Mario Dion.

But after stories broken by Canadaland and the CBC, it also confirmed that it transferred hundreds of thousands of dollars in speaking fees and expenses to the Prime Minister’s mother, mental health advocate Margaret Trudeau, and brother, Alexandre “Sacha” Trudeau, for events over the years. Some of the fees had been paid by the charity itself, not by its sister company. WE Charity said this was an administrative oversight, that the corporate arm would cover costs and that Trudeau family members were interesting speakers on their own merits.

The family entanglements of Trudeau’s finance minister added gasoline to the fire. It emerged that Morneau’s daughter was a WE employee, and that he and his family had travelled to WE projects abroad. By July 3, only a week after the program’s parameters were announced, WE pulled out.

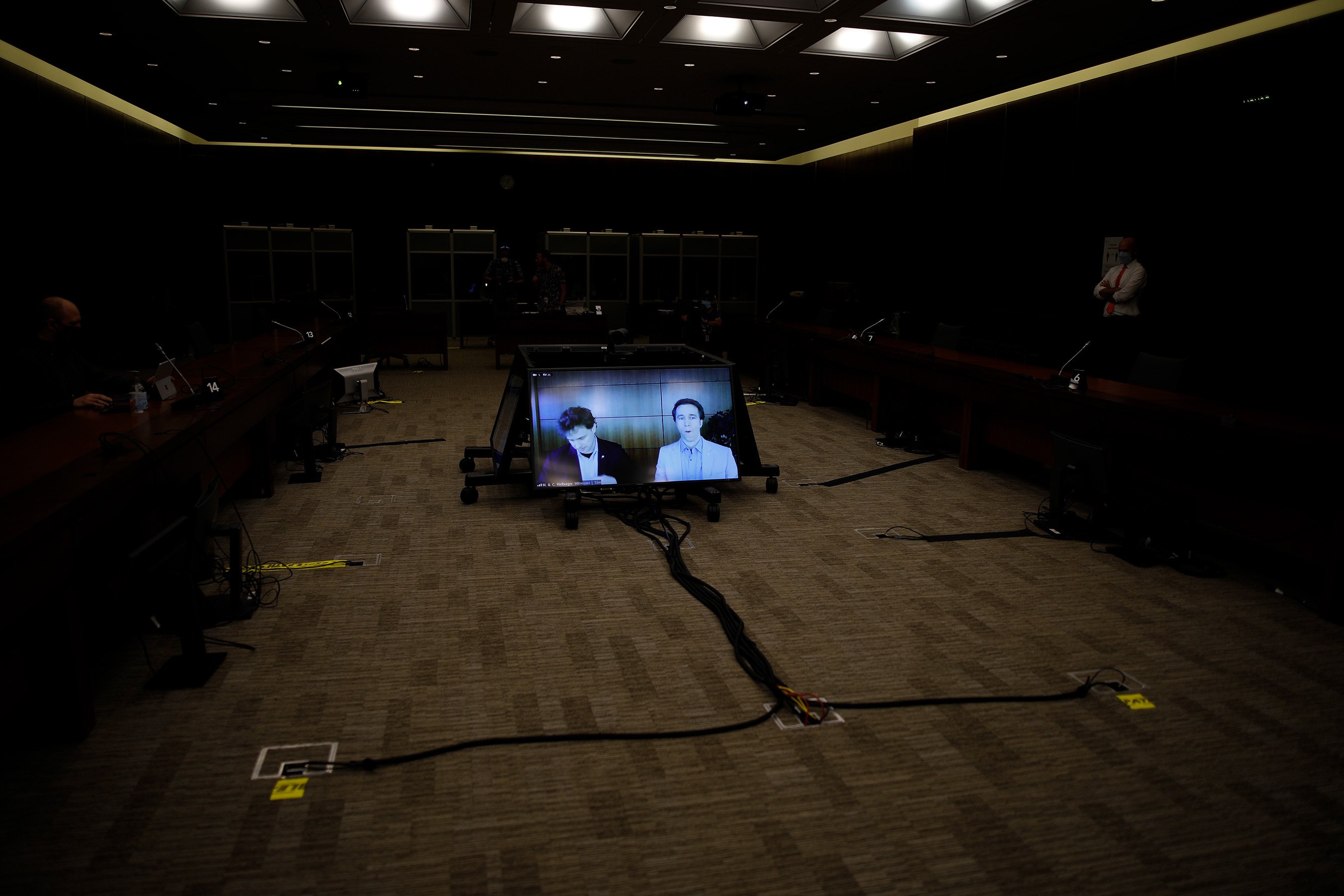

During the extraordinary set of virtual parliamentary committee hearings that followed, Trudeau testified that all he had wanted to do was support Canadian youth. He said he delayed the program’s approval by a couple of weeks, thinking that further “due diligence” would be required because he recognized a conflict of interest could be perceived. His own purported misgivings did not prevent him from participating in the final decision.

Trudeau and Morneau both apologized for failing to recuse themselves from the cabinet meeting at which the contribution agreement with WE was approved. Accused of cronyism, both are under investigation by Dion, and the RCMP stated in August that police are “examining” the matter. On the heels of a document dump that saw one official describe Morneau’s office’s relationship with WE as “besties,” the finance minister resigned.

'It’s questionable whether ME to WE will survive'

In testimony to a parliamentary committee, the Kielburgers were incredulous that any of this had been controversial, accusing Opposition politicians of misinformation. “We were not chosen for this work by public servants because of our relationship with politicians,” said Craig. “We were chosen because we are willing to leverage every part of our 25 years of experience to build this program at the breakneck speed required to have an impact on Canadian youth over the summer.”

The two stated the political scandal was “killing” them and “harming young people in this country in the process.” Marc said he wished they’d never answered the phone.

But disruptive as the political controversy became, McLeod says the pandemic is a greater threat to the organization’s future. “It’s questionable whether ME to WE will survive,” he says of WE’s for-profit arm. “If the pandemic didn’t hit, we would survive everything related to the government-program problems.”

Elizabeth Gomery, a founding partner at charity consultancy Philanthropica, is skeptical that WE was the only Canadian organization capable of administering a volunteer grant program. But she doesn’t blame them for jumping at the opportunity: “I think what happened was they needed to find a way to continue to operate and to continue to sustain some activity during a period of time where their traditional activities were no longer available. And this was a perfect way to do that.”

WE Charity executives promised to pay back government money received to administer the program. And the charity retroactively added its staffers to Canada’s federal lobbying registry, tracking dozens of communications with government officials since the beginning of 2019. Despite federal lobbying rules, it appears the charity will face no penalty for disclosing that information up to 18 months late.

***

Testifying via video call, with a Canadian flag and some framed photographs on a shelf behind him, then-finance minister Bill Morneau told the finance committee, and the country, he had made a mistake.

After his family took two trips to see projects administered by WE Charity in Kenya and Ecuador in 2017, Morneau said he realized he had never reimbursed the charity for staying at its accommodations and participating in its programming. Morneau said he wrote the charity a cheque for $41,000 the day before the hearing.

'The public thinks WE is a big actor, an important development agency. WE is not.

“The family asked to pay the highest possible cost that any individual could have paid to arrange similar experiences,” says Baker, the chief operations officer. (That means the difference between what Morneau paid and the actual cost was effectively a donation.) Offering complimentary trips to wealthy donors is an established strategy, Baker says, sometimes leading to significant funding for projects. He points to WE’s agricultural learning centre in the Amazon, which helps farmers tend sustainable crops, as an example: “This strategy and approach has been incredibly successful.”

Robert Fox, a former executive director of Oxfam Canada who advises international charities on good governance, says the approach is unusual—and is better suited to for-profit businesses that wine and dine clients.

Fox says the public has an impression that the WE organization is a much bigger player in the international development sector than it actually is, because of its celebrity connections and good marketing. For example, Save the Children International’s annual revenue is $2.9 billion, about 44 times more than WE Charity Canada’s $66 million in 2019. “Because the public knows so little about the sector and doesn’t know how many digits are involved in these things, they think WE is a big actor, an important development agency,” Fox says. “WE is not.”

Baker says the WE organization currently has a presence in places including Kenya, Ecuador, India, Ethiopia, Haiti and rural China. Its projects are wide-ranging, from conservation in the Amazon basin to the operation of a Kenyan hospital serving tens of thousands. In 2019, WE Charity reported directing $26.8 million toward international work—including $8.7 million to non-profits outside Canada—a little under half its total charitable program spending. The rest of the charity’s program spending—that is, total spending minus overhead—went to domestic programs, including WE Day and WE Schools.

In the fallout over the Canada Student Service Grant program, the WE organization promised a full-scale review of its operations. Its executives say its core purpose is still international development and that it intends to return to its roots.

RELATED: The Canada Student Service Grant’s unusual cabinet ride

This will likely prompt a reckoning over the type of work WE Charity does abroad, experts say. The kind of travel that sees Canadian teenagers parachuting into Thai communities for a week or two at a time is out of vogue. “International development has switched focus, by and large, to not having this sort of top-down, do-gooding, North America-coming-in-to-presumably-teach-local-populations-what’s-what approach,” says Gomery, the Philanthropica consultant. “This whole notion of having people come in to ‘save’ them is rooted in the idea that the communities don’t know what their problems are in the first place. It is deeply patronizing.”

Baker says WE Charity “genuinely and truly” partners with communities, and the WE Villages model is “designed to empower people to break the cycle of poverty” by helping communities become economically self-sufficient within an average of five years. “It is the adage about teaching someone how to fish versus giving a fish,” he says, adding that trips allow donors to witness the work they have funded.

The WE organization touts a 2012 report by charity impact assessment group Mission Measurement, which found WE’s international programs are effective, sustainable and cost-effective. Charity research organization Charity Intelligence more recently gave WE Charity an impact rating of “fair,” the second-lowest out of five possible ratings, based on publicly available information. WE Charity has said it didn’t have time or resources to participate in that review process, but claims additional data can demonstrate greater impact.

Amid scrutiny of the relationship between its charitable and business arms, WE points to two reviews from former judges finding the relationship between those entities to be transparent and legally compliant. Still, experts point out myriad ways in which the charity has managed to defy norms within the charitable sector. “I think it’s safe to say the charity sector has lots of problems and issues,” says Toronto charity consultant Ann Rosenfield, principal at Charitably Speaking. “WE seems to have all those times a hundred.”

For one thing, WE Charity’s financial statements show Craig and Marc Kielburger own the majority of for-profit ME to WE’s voting shares through a holding company. David LePage, managing partner of Buy Social Canada, which offers a certification program for social enterprises, says if a charity owns 100 per cent of shares of the businesses it operates, that guarantees profit flows to the charity and creates reporting requirements for all transactions. To his knowledge, ME to WE is the only company connected to a Canadian charity that doesn’t operate this way.

According to Baker, the reason for that is that the Kielburger brothers decided in 1999, on legal advice, that their charity should not own its sister company, then called Leaders Today, for liability reasons. The Free the Children board worried that a liability issue, such as a participant getting injured, could bring down the charity.

Another grey area is that WE Charity routinely promotes ME to WE’s products and services. For example, materials for the charity’s educational program, WE Schools, include promotions for ME to WE trips and suggests selling bracelets as a curriculum “activity.” In the 2019-20 academic year, a little under $75,000 in bracelets were purchased through a WE Schools campaign, according to the charity. “It is important to note that ME to WE Social Enterprise does not make any profit on this program,” the charity says in its statement. “This program is solely to support the women artisans and to assist with school fundraising goals.”

Even so, the appearance that the charity is being used to further ME to WE’s business interests hurts the credibility of other social enterprises in the public eye, LePage says. “Using the charity to create profits is actually pushing the line of what I think even the CRA or any of us in the sector would recommend,” he says. “When you start pushing private value through the activities of the social enterprise, you start to lose the integrity of the social enterprise concept and brand.”

The WE organization’s governance structure, too, is unusual. The two entities share a chief financial officer, and three of WE Charity’s five board members (four of them new, after Michelle Douglas’s departure) have previously worked for or with the ME to WE company. Baker, the chief operating officer of WE Charity, says periodic board transitions are normal and a sign of a commitment to strong oversight. He says the organization put him and other executives on the boards of related entities “to ensure a clean line of accountability to the overall WE Charity board of directors.”

But Kate Bahen, managing director of Charity Intelligence, says boards should be independent from the charities they oversee: “As a WE donor, as somebody who donates to WE Charity, I would want an independent director who hasn’t previously worked with Marc Kielburger.”

WE executives also sit on the boards of many related, but separately registered, charities and foundations. A parliamentary committee’s request for a full list of all WE’s related entities was not fulfilled before prorogation, but filings show that, in addition to WE Charity Canada and ME to WE, at least 11 more entities exist in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K.

In its statement to Maclean’s, WE Charity said there has been a “high level of misunderstanding” about the number and purpose of WE-related entities. The charity and its sister company carry out “the vast majority of the overall organization’s work,” while other entities have been established over time for one-off purposes or as required by government in other countries where WE operates. Announced in July, a review by Korn Ferry, a global organizational consulting firm, is tasked in part with streamlining the WE organizational structure—including ensuring a “clearer separation of the social enterprise from the charitable entities.”

Some affiliated entities have tiny budgets and little indication of an operating purpose. One such entity, WE Charity Foundation, was used to sign the contribution agreement for the Canada Student Service Grant program. The Kielburgers said in their committee testimony that it had been set up to limit liability, but CRA filings listed its purpose was to hold real estate. In its statement to Maclean’s, the charity says that “in the initial application to the CRA, holding real estate was briefly considered, but this never occurred.” The foundation does not hold WE Charity real estate assets, the statement goes on, and its mandate was formally altered with the CRA prior to its signing of the contribution agreement.

WE Charity owns about $44 million in real estate, according to its financial statements. (An analysis by the National Post found that number for the entire WE organization was closer to $50 million.) About $30 million accounts for the charity’s hub, the WE Global Learning Centre in downtown Toronto, according to Baker. Nearby properties were acquired to establish a “campus for good” tied to the organization’s 25th anniversary this year, for which plans have been put on hold.

The charity says it doesn’t use funds designated for projects, or raised by schools or children, to buy property—it holds real estate as a reserve fund it can access in hard times, and its use for office space cuts administrative costs. But Fox, the former Oxfam director, says it is rare for charities to acquire and use property in this way.*

The Kielburger brothers testify before the parliamentary finance committee on July 28 (Photograph by Blair Gable)

***

Is WE an international development charity? A youth movement? A school volunteer program? A purveyor of handmade jewellery? The organization’s streamlining initiative goes on. But as it stands, WE would be hard-pressed to come up with a clear, 30-second elevator pitch. And that is a problem, charity experts tell Maclean’s. It isn’t just facing an existential crisis, but an identity crisis, too.

On top of pandemic losses, school boards are reviewing their participation in WE programs in what the charity calls “by far the most challenging seven months in the organization’s history.” Major WE Charity corporate partners including Royal Bank, Telus, KPMG Canada and Virgin Atlantic either froze or ended their support after the political crisis.

“Never could we have imagined that the combination of COVID-19 and the political fallout of the CSSG could be so devastating for WE Charity, our staff and the millions of beneficiaries of our programs and projects around the world,” WE Charity says. The organization let go an additional 16 full-time workers and 51 contractors in August. Its U.K. operations are also being centralized to its Canadian headquarters, resulting in a loss of 19 full-time and contract employees.

In the U.S., where there is little coverage of the controversy, sponsorships have been less affected, with educational partners, corporate supporters and donors still “highly engaged” despite the pandemic. But even there, WE’s future is uncertain.

“Has there been a setback? Oh my god, yes. But right now, truly, all efforts are going to minimize damage to staff and progress and protect global projects,” says David Stillman, the charity’s former U.S. director and a current member of the U.S. board. “I personally think it’s shameful that 25 years of work could get lost in the political crisis.”

If peculiarities with the organization’s structure have been revealed in the past few months, Stillman suggests they do not come from an intention to obfuscate, but from a commitment to pioneer new ways to conduct charitable work in Canada. To use his metaphor, the Kielburger brothers would sometimes “build the plane as they were flying it.”

Enormous loss could come from dismantling the WE empire, says Susan Phillips, a professor at Carleton University and an expert on the non-profit sector. The organization had succeeded in reaching high school students and nurturing in them a desire to serve others. Its relationships with schools would be hard to replace.

'The only way Marc and Craig will survive this is if they step away—but they won't'

More pressingly, Phillips says, the reputational hit the WE brand is taking, and the glut of reporting on the murkiness of its operations, will damage the charitable sector writ large. “Because of the pandemic, you have a lot of international organizations in financial trouble,” she says. “And the work that’s going to need to be done in low-income countries is going to grow incredibly.”

A lot needs to change for WE to re-earn donors’ trust, says charity consultant Ann Rosenfield. “Their governance structure makes no sense and is unaccountable, which we hear from the testimony of their chair. Their incorporation structure is Byzantine at best and unaccountable and needs to change. They have fuzzy roles as founders, which ultimately make them accountable to no one,” she says. “The Kielburger brothers and family and WE need to be two separate entities.”

She and others interviewed by Maclean’s describe WE’s predicament as a case of “founder’s syndrome.” Founders get caught up in growing their movements and trying to change the world. But at a certain point, the organization gets bigger than they are capable of dealing with. Instead of ceding control to independent directors, they cling to the helm.

It’s “very difficult” for founders to take a step back from their “baby,” says Carleton’s Phillips. But to re-establish trust, that can be necessary. And in this case, she thinks it is. “You’d need a strong independent board who is going to move it in a different direction. To do that, the founders would voluntarily need to step away,” she says.

In a written statement, the Kielburgers did not directly respond to the calls for them to step back. The brothers remain focused on “anchoring the goodness that young people have created at home” and “protecting the integrity and long-term sustainability of our development projects abroad,” the statement says. “We hope to continue to support and inspire a generation of young people while preserving and continuing 25 years of impact.”

A former WE staff director, who would not speak publicly because they still work in the sector, put it bluntly: “The only way Marc and Craig are going to survive this is if Marc and Craig step away, and they won’t, because their egos are too big. They made decisions that grew the organization to a place that it couldn’t sustain itself anymore.”

The brothers learned early to build influence in their pursuit of good intentions, often challenging assumptions about the essence of charity. And as they grew, the movement known as WE evolved in their image.

In 1996, that image was of a 13-year-old Craig, shoulder-to-shoulder with the children he wanted to help, fighting for the attention of a prime minister.

In 2015, that image was of two polished men welcoming to the stage a fellow of their own ilk—a leader who had grown up in the spotlight and spoke compassionately about the country’s amorphous “youth.” Two men literally embracing the sort of powerful figure their younger selves were ready to make sweat for having “vague” ideals.

They’ve come a long way.

EDITOR’S NOTE, Sept. 14, 2020: An earlier version of this story quoted Robert Fox as saying it’s rare for international development charities to own property. Fox clarifies that many large ones do own their headquarters.