A mysterious sighting in the Manitoba manhunt—and then the trail goes cold

Bear Clan Patrol members were confident they’d spotted Schmegelsky and McLeod, but the police appear to be back at square one

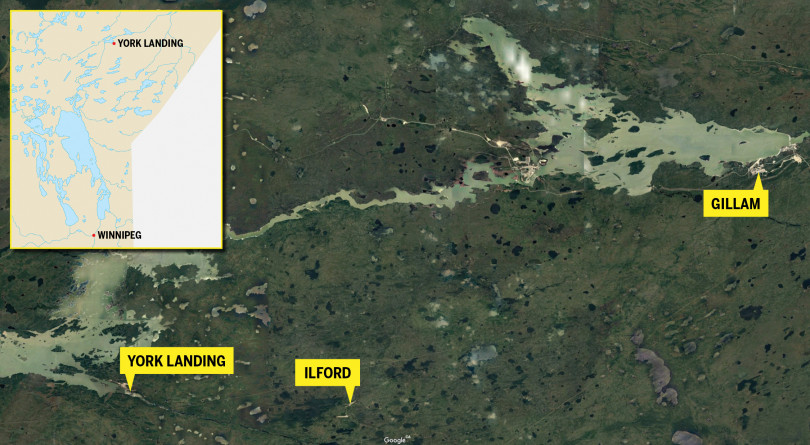

RCMP searching the area near Gillam; even from the air, the fugitives would be hard to spot (@rcmpmb/Twitter/CP)

Share

At first, the two men rummaging through the garbage dump looked to Travis Bighetty like contractors or sewage workers. They were tall and slender—white and male in appearance—and appeared to be stumbling along. One wore a grey hoody; the other a green camouflage jacket. “They fit the description,” says Bighetty, the Bear Clan Patrol coordinator from Winnipeg who reported the sighting on Sunday during the group’s last patrol of the day. They were about 40 yards away. He, along with two others, didn’t see the men’s faces, but after three years with the Bear Clan he can tell when people are trying not to be seen.

The dump is a man-made pit filled with trash found on the western edge of the York Factory First Nation, a community of about 400 people also known as York Landing. Plastic bags and broken appliances like TVs and laundry machines are scattered throughout the grounds. Black bears roam the area in search of food, making it a place people don’t go to without a car. And Bighetty noticed that these two men didn’t have one. Nor were they armed, or carrying anything else. Seconds later, they slipped into the bush and out of sight.

Shortly after Bighetty reported the sighting, dozens of RCMP officers—followed by media crews from around the world—descended on York Landing by air and boat, shifting a massive, multi-agency manhunt that had been primarily focused 200 km northeast, in Gillam, Man. Response teams searched through the night while helicopters and a military aircraft known as a Hercules surveilled the ground from the skies. Residents of York Factory stayed inside and locked their doors. But the Mounties didn’t find their quarry, and by early Tuesday the surge of resources was over.

Chalk up another frustrating episode to the nationwide manhunt for Bryer Schmegelsky and Kam McLeod, the childhood best friends suspected of killing three people in B.C., who are still believed to be somewhere in the forests of northern Manitoba—where the bugs alone are enough to drive a person mad.

Bighetty and the Bear Clan had arrived in York Factory the day before to provide support to the community amid the heightened police presence in the region. On the day of the sighting, Bighetty says his group, made up of volunteers, spent 10 minutes looking around the area before sounding the alarm. Then they went back. “Even though Gillam is a few communities away, York Factory is still close by the train tracks and the hydro lines and trap lines,” he says. Locals had told Bighetty when he arrived that they had trouble sleeping knowing the situation unfolding around Gillam. “There are winter roads, which [in the summer] is kind of like a tree line that is open,” he notes. “If you see it, then it’s your one clear path to somewhere.”

Franklin Ponask was enjoying his evening when a neighbour told him that the two fugitives were spotted in York Landing. He lives in a row of houses closest to the dump. He grabbed his 12-gauge rifle and, along with another gun-carrying local and two band constables, created a perimeter between their homes and the dense bush around them. Ponask says he was just trying to protect his family: “I was ready to do what I had to do if they were around.” Later, when he tried to get some sleep, he could hear the buzz of planes and the rumbling of police trucks through the night.

Locals say things like this don’t normally happen in a place like York Factory. Much like Gillam, it’s quiet and small—people leave their doors unlocked and their keys in their car ignitions. With the winter-time ice roads long gone, the First Nation is reachable only by ferry or airplane. Ponask wonders how two individuals with no knowledge of the terrain could endure the region’s harsh elements. “Berries for survival,” he guesses.

Band constable Isabel Beardy lives across the road from Ponask. On the night of the sighting, she patrolled all night, then returned home for four hours of sleep and then went back out again. “It’s pretty much a dead end,” she says of the area where the two suspects were seen. “There’s nothing but swamp and muskeg back there. We’re on an island, so they’re pretty much isolated.” Because there are ways to get to York Landing on foot, Beardy didn’t doubt that the fugitives may have been spotted in the community. But finding them isn’t easy as it sounds. The bushes are dark, dense and boggy. Even an ATV will only get you so far.

Which is why frustration has mounted as the hunt drags on. For the most part, Beardy’s pleased with how the RCMP has kept the community informed. But she questions why they haven’t used local guides. “They do know what’s out there, but I’m pretty sure they’d have a better idea if they had a guide from the community,” she says. “It’s a safety concern and we understand. But we want to catch these guys, too.” (Band constables perform their jobs unarmed.)

On Tuesday, it had been a week since Schmegelsky, 18, and McLeod, 19, were named suspects in the deaths of American Chynna Deese and her Australian boyfriend Lucas Fowler. The couple, both in their early twenties, was found shot dead on the side of a northern B.C. highway. Just four days later, the body of Leonard Dyck was discovered 500 km away near Dease Lake, two kilometres from the burned truck belonging to the two suspects, who were then reported missing. The RCMP have since charged the two men with second degree murder in the Dyck death. The pair had left their homes in Port Alberni on Vancouver Island earlier this month, making their way north in a pickup truck with a camper to find work to the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

Canadians have learned more about the fugitives in the days since. They shared a disturbing interest in Nazism and followed online video game accounts that exalt Soviet Russia. Schmegelsky’s father told media that the two men considered themselves survivalists, and have spent much of their time over the past two years in the woods.

The hunt for them has stretched across the country’s quiet and sparsely inhabited northern highways. They were seen in Jade City, in northernmost B.C., on July 18; three days later, on July 21, security cameras in Meadow Lake, Sask. caught them leaving a Co-op store; on July 22, before they were named suspects, safety officers in Split Lake, Man. (Tataskweyak Cree Nation) pulled them over as they drove into the dry community to get gas; the next day, their vehicle was found on fire a few kilometres outside the Fox Lake Cree Nation, northeast of Gillam. There’s only one road leading to both communities from the nearest Manitoba city, 300 km away, with few places to stop in between. It’s the end of the road. Signs issue a warning that those tough enough to build lives up here take to heart: travel with survival gear.

Fox Lake residents Billy and Tamara Beardy noticed the billowing black smoke while out berry picking nearby. The region is prone to forest fires, so they went to see whether they should call a conservation officer. But it was the burning vehicle, which had been pushed into the ditch. For nearly an hour, the couple sat there in their truck, doors unlocked. Billy guesses it had been burning for no more than 15 minutes. Tamara says that when they went back to the vehicle a day later, responders had flipped it over. Sardine cans, propane bottles, forks, orange peels, pork chops, money, tools and keys littered the road.

Both communities have been unsettled by a sense of fear and anxiety. “Everything’s changed,” says Tamara. “We have a shotgun in our room.” Billy and others had started patrolling the community at night to help residents feel at ease.

The next few days saw police swarm the region, going door-to-door and searching buildings and empty shacks in Fox Lake and Gillam. But those search efforts, too, have been unsuccessful, frustrating not just residents—eager to see their lives go back to normal with a definitive conclusion—but also police. It’s led authorities to mull over the possibility that Canada’s most wanted may have been helped out of the area by someone who didn’t recognize them from the pictures and posters thrown up all over the Internet and in Gillam. The Mounties are fighting two battles: one with false sightings and rumours emerging throughout the country, and one with the landscape itself.

The region is vast and unforgiving. Northeast of Gillam lies Hudson Bay, and at this time of year polar bears are known to wander off the melting ice. There are also black bears, wolves and wolverines (touching down in York Landing, officers had to chase bears off the runway). The flies and mosquitoes are just as ferocious as the earthbound predators. Swampy muskeg makes travelling on foot difficult without sinking or getting trapped and wet. And trapper’s shacks offer hiding spots. Billy Beardy doesn’t believe it’s possible for two people to survive this long in the woods without knowing the region. “Unless you have a big sack of food,” he says. “Half the water around here will give you the beaver fever.”

Clint Sawchuk, the owner of Nelson River Adventures in Gillam, agrees, but notes the self-same conditions make searching difficult. “They could be 10 feet off the road and you wouldn’t see them,” he says. “It’s all low-lying trees, not high timber. It’s all spruce trees and small brush. If they wanted to hide, they could easily hide.” Sawchuk admits he’s been sleeping with a gun. But if they’re out there, he says, “they ain’t enjoying their stay.”

By late Monday in York Landing, though, it was clear the fugitives had either escaped or were never there, raising unspoken questions as to whether the Bear Clan Patrol had seen what they thought they had. The RCMP put out statements diplomatically saying they still hadn’t “substantiated” the sighting, while many of the officers deployed in the community—and many members of the media—went back to Gillam.

It was a message many worried residents found hard to accept. Even in the absence of physical evidence like a burned-out car, the account seemed relatively solid: clear and detailed descriptions based on a sighting by three witnesses from a stone’s throw away. And why, if they weren’t the suspects, would the two men run off?

So residents remained on alert on Tuesday, and kept their watch. More members of the Bear Clan Patrol, previously in Gillam and Fox Lake, flew in to support the community. “I’m very proud of my community and how we’ve volunteered in the search,” Isabel Beardy says. “The men around here know the land and they’re really protective of our community—we all are.”

In a strange way, even as some of the police resources are pulled from the First Nation, the band constable of six weeks has seen her community come together to face whatever’s out there. “I just started,” she says. “What a time to take responsibility.”