And don’t come back: The rare case of a man banished from his province

A serial offender recently chose to be cast out of Newfoundland and Labrador instead of going to prison. Not everyone agrees that’s the right solution.

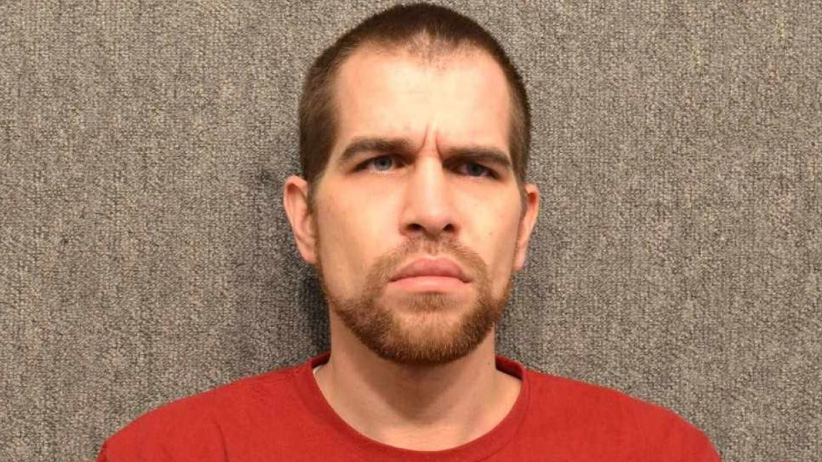

Mugshot of Gordie Bishop on January 2, 2015, after he broke into Peter Easton’s Pub, then dragged a police officer with his car. (RNC)

Share

Gordie Bishop’s criminal record covers 27 pages. It includes a string of property offences and assaults, all of them committed in Newfoundland and Labrador. He’s very familiar to members of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary. Their latest encounter with the serial offender—and their last, if things go as hoped—was two years ago, as officers responded to an early-morning alarm inside a local pub.

Another Bishop break and enter. The suspect fled the scene, leaving footprints in the snow. A constable tracked him to a small black car. As she reached inside the vehicle to try to stop him from driving away, Bishop hit the accelerator. The cop fell to the pavement and suffered injuries.

Later the same day, another officer spotted Bishop as he parked the black car. She approached; he attempted to motor off again, but instead crashed into an unmarked police cruiser, injuring its driver.

The jig was up. Bishop was arrested and charged with 13 offences. He went on trial earlier this year and was found guilty of six counts, including two counts of assault on the officers.

Ordinarily, Bishop would have been sent to prison; after all, as a Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador judge noted, his crimes warranted a custodial sentence of more than two years. But in July, his counsel stood before Justice Alphonsus Faour and asked for a different sort of punishment. Bishop wanted banishment. For a whole year, from his native province, all 405,212 sq. km of it. A place which, in his 33 years, he’d never left.

Banishment orders are rare in Canadian courts. While there is precedent, most are prescribed as part of an offender’s probationary conditions, covering periods after he or she has served prison time. In almost every case, the offender agrees to stay away from a relatively small area—a neighbourhood, a city, a reserve—for a specific amount of time.

Cases in which a convicted person has volunteered to quit an entire province rather than go to prison are almost unheard of. Bishop’s unusual proposal, to which the Crown consented, “is to remove him from associations within this province which have been negative influences on him,” Faour noted while delivering his sentencing decision in St. John’s.

“The banishment order does two things,” the judge explained. “First, it protects the community by removing Mr. Bishop from the area in which he has committed many offences. Second, it serves his rehabilitation by removing him from the circumstances which trigger his criminal activities, which in turn facilitates protection of the community.”

The gavel dropped. Bishop left the courthouse, and, presumably, the Rock. He’s not giving interviews, and neither is his lawyer; however, Bishop’s father told reporters that the hapless repeat offender will likely spend his banishment stretch in Fort McMurray, Alta., where his mother lives.

Some Fort Mac folk aren’t pleased with the prospect. “It’s just a slap in the face to the people of Fort McMurray,” one current mayoral candidate, Allan Vinni, told the CBC.

The Canadian Police Association (CPA) expressed outrage as well, saying Bishop’s assault on two officers requires hard time, not a cross-Canada trek. “Making a long-term offender someone else’s problem isn’t an effective long-term solution,” CPA president Tom Stamatakis said.

The same concern has been raised inside Canadian courtrooms, where judges are traditionally reluctant to order banishments. “For a community to think in terms of unburdening itself of an undesirable individual by saddling a neighbouring community with him smacks of a lack of civic responsibility and unthinking behaviour, particularly where the individual grew up in, and was a product of, the first community,” a Saskatchewan Court of Appeal judge wrote in 1982 while reversing a trial court decision that banished, for one year during probation, a criminal from the village of Île-à-la-Crosse, Sask.

Another consideration: do banishments actually work? Can they help the offender rehabilitate? It seems no one knows. “There are no statistics specific to banishment and its effectiveness,” says Lorne Neudorf, an associate professor of law at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, B.C. “Most critiques are based on case studies, and they focus on the concern about criminals being foisted on other communities.”

Convicted of sexual assault and banished from his reserve in Saskatchewan for a year, William Bruce Taylor wasn’t foisted on anyone. In 1995, he was dispatched to a “remote island” on Wapawekka Lake in the province’s northern reaches, where he was to maintain a small cabin provided for him, cook for himself, chop wood and mull over his crimes in solitude.

Or that was the plan. “As it turned out, the island on Wapawekka Lake proved to have been ‘a party island,’ ” the province’s appeal court later noted. “Moreover, the cabin there had been broken into and everything stolen.” Taylor was moved to another island on a more isolated lake, where he served the rest of his banishment.

In 1998, Taylor was arrested and charged in another alleged case of sexual assault. The case was eventually dropped when his purported victim—pregnant with Taylor’s child—abandoned her complaint. Taylor was relieved; according to his lawyer, that year spent in isolation, albeit interrupted, wasn’t one he wished to repeat. Whether anyone benefited from the banishment remains an open question.

MORE ABOUT JUSTICE:

- Alberta court orders new trial for man acquitted of murdering Cindy Gladue

- Are pigs people too? Here’s what the judge in the ‘pig trial’ said.

- Ontario’s ‘poetic’ judge is back with another ruling

- What’s at stake in the case of Justice Robin Camp

- The ethics of police using technology to predict future crimes

- Hundreds of suspected criminals could be about to go free

- A closer look at the rise in hate crimes in Canada

- How reporting on a murder trial stirred memories of my brother’s death