As Trudeau takes power, judge adjourns citizenship court battle

Convicted terrorists looking to keep Canadian citizenship agree to pause a constitutional challenge as Liberals weigh how to keep their promise

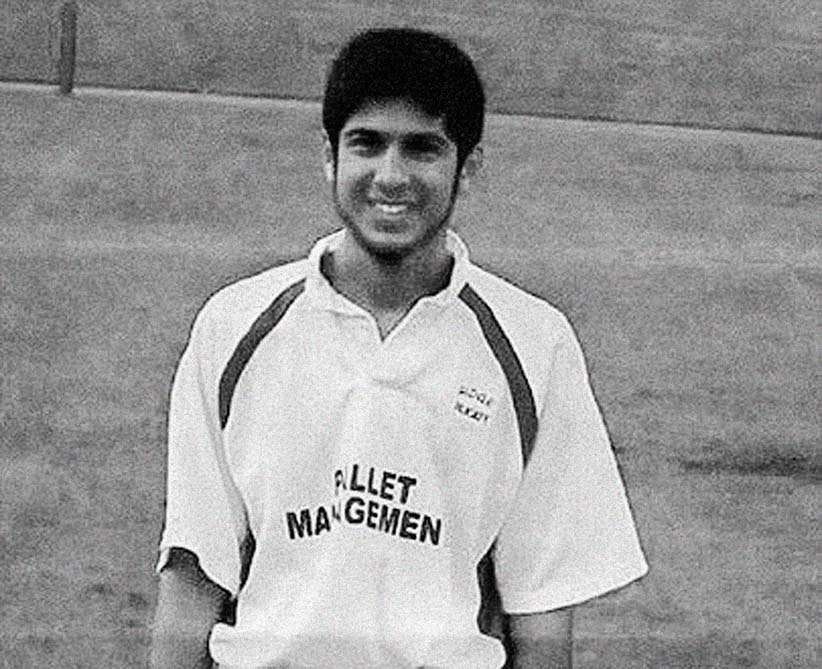

SAAD GAYA

Share

As Justin Trudeau walked toward Rideau Hall this morning, federal lawyers were ready to act on one of his key campaign promises: scrapping the controversial Conservative law that gives Ottawa the power to strip convicted terrorists of their Canadian citizenship.

Last week, the Justice Department requested an indefinite adjournment in five high-profile court challenges targeting the Harper-era revocation law, saying federal lawyers assigned to the cases can’t move forward without direction from the incoming Liberals. “Given the election outcome resulting in a new government, we are seeking instructions on next steps in this litigation,” says an Oct. 27 letter from senior counsel Angela Marinos, filed with the Federal Court in Toronto. “Given that there will be a transition period after the Cabinet is sworn in, we cannot confirm, at this time, when those instructions will be conveyed.”

Lawyers for all sides consented to the adjournment request, and the order was rubber-stamped by Justice Russel Zinn on Monday—48 hours before Trudeau and his ministers were to be officially sworn in by Governor General David Johnston.

The adjournment essentially hits the pause button on a cluster of court cases that triggered intense debate during the election, giving the new PM and his advisers plenty of time to determine how best to repeal the Tory law, as promised. All parties to the court actions are scheduled to reconvene on Dec. 9 for a case-management conference in Toronto; by then, the Liberals’ specific intentions should be evident.

At the centre of any discussions will be the new justice minister, rookie MP Jody Wilson-Raybould, and veteran Liberal John McCallum, sworn in as minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship.

“It’s quite reasonable for the government lawyers to ask for a pause while they seek new instructions from the incoming minister, and we will wait and see what they bring forward,” says Josh Paterson, executive director of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, which launched one of the constitutional challenges on behalf of convicted terrorist Asad Ansari, 31. “We’re very hopeful that the government will follow through on their promise.”

That promise—repeated throughout the long campaign—was to rescind certain sections of Bill C-24, a Conservative law that allows the government to revoke the citizenship of anyone convicted of serious crimes against national security, including treason, espionage and terrorism—providing that person is a dual national who holds citizenship in a second country. (International treaties do not allow Ottawa to render a person stateless, which means that, under the legislation, terrorists who hold only Canadian citizenship cannot lose their status.)

Stephen Harper’s Conservatives trumpeted the law as an invaluable tool in the fight against the “ever-evolving threat of jihadi terrorism,” noting that it’s applied in only the most egregious cases. Just 10 people have been served with a “Notice of Intent to Revoke” since the law took effect on May 29, and only one—Zakaria Amara, the confessed ringleader of the 2006 “Toronto 18” bomb plot, now serving a life sentence—has actually lost his citizenship.

Five of those convicted terrorists have since launched Charter challenges in Federal Court, arguing, among other things, that Bill C-24 is unconstitutional because it amounts to “cruel and unusual punishment” and creates “second-tier citizenship” by singling out dual nationals. One applicant, Saad Gaya, was born and raised in Canada, yet faces the possibility of being deported to his parents’ homeland of Pakistan, a country he’s never lived in.

There is no dispute that these men were terrorists. Hiva Alizadeh, an Iranian-Canadian, learned bomb-making techniques in Afghanistan, pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden and is now serving 24 years behind bars. His Pakistani-born accomplice, Misbahuddin Ahmed, was sentenced to 12 years. Gaya and his friend, Saad Khalid, were arrested at a warehouse north of Toronto, following Amara’s orders and unloading what they believed to be three tonnes of explosive fertilizer. And Ansari, also born in Pakistan, was convicted in connection with the “Toronto 18” conspiracy.

What is up for debate, however, is whether these convicted terrorists—despite their grievous crimes—deserve to be stripped of their Canadian citizenship, a punishment akin to banishment.

Trudeau came down clearly on the “no” side. “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian,” he said many times on the campaign trail—and one more time during his election-night victory speech on Oct. 19.

The ball is now in the new Prime Minister’s court, says Lorne Waldman, a Toronto lawyer who represents two of the men fighting the government’s revocation attempts. “I am very hopeful that the constitutional challenge will become unnecessary because of the changing government,” he says. “Given what Prime Minister Trudeau said very unequivocally during the campaign, I would expect this constitutional litigation will not be necessary.”

What happens next, though, is not entirely clear. The Trudeau government could decide to withdraw all notices served to date, eliminating the immediate threat of revocation and rendering the court cases moot. But striking down the law itself will require an Act of Parliament, a process that could take many months, if not years. As for Amara, restoring his Canadian citizenship appears simple enough—as long as the political will exists.

“Under the Citizenship Act, the minister has the ability to grant citizenship to anybody they please, so they could fix any revocations that have already been done,” Paterson says. “They could also, in any new legislation, have a decree that says any revocations that took place under Bill C-24 were null and void.”

If nothing else, the Federal Court adjournment gives the Liberals some time to figure out the best route forward. “Prime Minister Trudeau made it abundantly clear that he’s going to repeal this,” Waldman says. “But, given there are so many things this new government is going to have to focus on, it may take a while.”