Canada’s extremist problem

Why the RCMP’s new counter-extremism program won’t help deal with terrorists returning from Syria

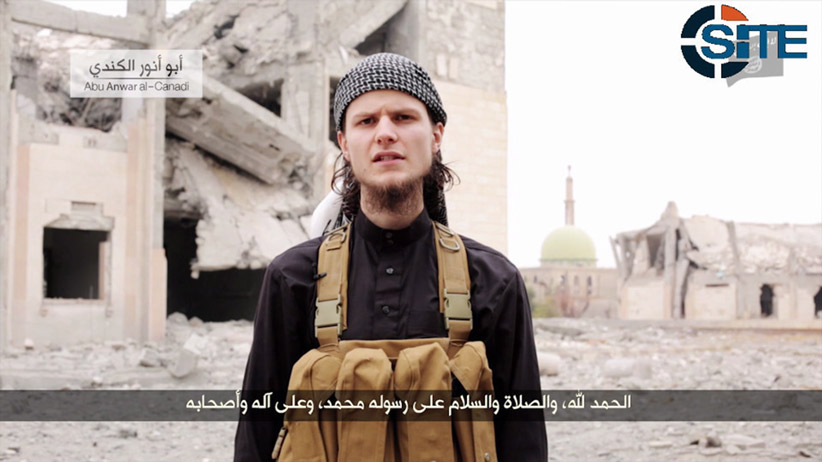

SITE Intelligence Group, a U.S.-based company that monitors trends within the global jihadist movement, says Islamic State has released a video calling for lone-wolf attacks on Canadian targets. On the video is a man who says he is a Canadian and identifies himself as “Abu Anwar al-Canadi.” THE CANADIAN PRESS/ho

Share

“I was one of you. I was a typical Canadian,” John Maguire says in a recent propaganda video released by Islamic State, a jihadist group that controls large chunks of Syria and Iraq. In it, he stands in front of a shattered building and holds an assault rifle.

“I grew up on the hockey rink, and spent my teenage years on stage playing guitar.”

Maguire is not so typical anymore. But nor is he unique. The Ottawa-area man, identified in the video as Abu Anwar al-Canadi, is one of about 130 Canadians the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) says are now fighting with banned terrorist groups overseas.

Maguire urges his fellow Muslims to join Islamic State, or attack other Canadians at home. “You either pack your bags, or prepare your explosive devices,” he says in the video. “You either purchase your airline ticket, or sharpen your knife.”

Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney says Canada has revoked Maguire’s passport. While Canadians who are not dual nationals cannot have their citizenship revoked for terrorism-related offences, losing his passport may mean that Maguire will never make it back to Canada. But, according to CSIS, 80 Canadians who joined banned terrorist groups overseas have now safely returned.

RELATED: CSIS has tabs on radicalized Canadians who have fought abroad

Canadian law makes it a criminal offence to join such groups. But collecting evidence and building a case can be difficult. Of the more than 200 Canadians CSIS says have been involved with banned groups abroad, including those who have returned to Canada, only one, Hasibullah Yusufzai, of Burnaby, B.C., has been charged with a terrorism offence. (A second Canadian who traveled to Syria has been charged with passport fraud.)

CSIS director Michel Coloumbe told a House of Commons committee the returnees took part in “terrorist-related activities.” The RCMP says they “pose a significant security threat” to Canada. And yet the vast majority, it appears, will never be criminally charged.

What to do with such individuals is an increasingly pressing challenge for Canada, and other countries around the world, as hundreds of foreigners flock to Syria and Iraq to join Islamic State. Keeping all returnees under constant surveillance consumes massive amounts of time and resources. Ignoring them is risky. Some Western countries are experimenting with a different option: de-radicalization.

Britain, from where some 500 to 600 aspiring jihadists have joined Islamic State, allows police to decide whether a returnee might benefit from a program of rehabilitation. If so, religious and community leaders, social workers and psychologists can be enlisted to help with an intervention. In Germany, at least one government-funded organization advises family members of those who are considering joining an extremist group abroad, or have already done so, with a view to helping relatives convince their loved ones to abandon Islamist extremism. In neither case does participation in a de-radicalization program preclude the possibility of criminal charges.

In Canada, the RCMP is launching its own “countering violent extremism program.” It sounds similar to de-radicalization programs in Europe, and indeed Canada researched and adopted practices from some of them. But the RCMP insists it is not involved in de-radicalization, but rather “disengaging” individuals from a trajectory toward criminal activities.

“De-radicalization is about ideas, ideology, and that is not our expertise as law enforcement. We cannot police people’s thoughts,” says Sgt. Renu Dash, of RCMP public engagement.

“If there is a situation where we have someone on the pathway to criminality, we want to disengage them from that criminal behaviour. We’re looking at vulnerabilities in the very early stages.”

The RCMP does say its goal is to help people and communities resist “the dangerous narrative employed by violent extremist groups” — though Dash is at pains to point out that the criminality the RCMP is hoping to divert people from could be anything from drugs and guns to prostitution, as well as terrorism. And in practice, the tactics employed are meant to be flexible.

The program is built around “hubs” whose members are made up of a cross-section of a community, including local RCMP members. They meet regularly and try to identify individuals who are potentially heading for trouble. Others, such as teachers, family members or faith leaders, are then brought in to work directly with the vulnerable individual. If there were to be an attempt to persuade someone that his interpretation of a faith is misguided, it would happen here.

“The voices have to come from the communities,” says Dash. “We will bring them to the table. The communities are best placed to have the conversation. Not the police.”

If successful, the RCMP’s new counter-extremism program may prevent other young Canadians from following Maguire to Syria. Crucially, however, it won’t help those who have already left, and those who have returned.

“Our objective is absolutely working in the pre-criminal space,” says Supt. Shirley Cuillierrier, director general of partnerships.

“We’re not dealing with returnees. That falls in the criminal sphere.”

Usama Hasan, a British imam and senior researcher at the Quilliam Foundation, a counter-extremism think tank in Britain, says he is “astonished” that Canada does not have a de-radicalization program for Canadians who have returned from Syria and Iraq.

“There may be a risk that they’ve spent time with extremist groups and been brutalized by the war. So there’s always a risk that their minds won’t be thinking straight. So it’s very important to have ‘de-rad,’ which has to include a bit of mental health counselling and looking at PTSD and things like that,” he says.

“Even if they are prosecuted and convicted, you still need to de-rad them, because they will eventually be released from prison, and quite possibly they will be even more of a threat then because they will have been hardened in prison, and so they’re a threat either way.”

When he was a student at Cambridge University in the early 1990s, Hasan left Britain and briefly joined the Islamist insurrection, or jihad, against Afghanistan’s communist government.

At the time, Hasan was a radical Salafist and followed an extreme interpretation of Islam. He has since become much more moderate. In addition to officiating at interfaith marriage ceremonies, he now advises the British government on its own de-radicalization program, dubbed Channel.

People immersed in extremist groups “live in a kind of disconnected world,” says Hasan.

“They have their own reality, which they invent and perpetuate among their group by repeating the same old propaganda over and over again, but also blocking out anything that runs counter to that world view. We have to find holes in their world view and try to get through to them in as many ways as possible to make them doubt and rethink those kinds of ideas.”

Has likens the process to convincing someone to leave a gang. “You have to give them alternatives, address their needs,” he says.

When extremists rely on their faith to justify their world view, “you have to address all those religious points as well,” he says, “with better religion.”

Hasan describes recently counselling a young man who was determined to go to Syria. Hasan says the man knew “almost nothing” about the conflict there, or about the Middle East in general.

“People had just told him it was a war between Muslims and non-Muslims, and it was his duty to go and fight for Islam.”

The man believed there were American ground troops in Syria whom he could fight. Hasan educated him about the war, especially its sectarian nature and the ongoing slaughter occurring between Muslims. The potential recruit decided to stay in Britain.

He was lucky. Many others have left from Britain, Canada and other Western countries and died far from home. Some have committed horrific atrocities. Some will come back. Whether we like it or not, we’re going to have to figure out a way to live with them.