Canadians support journalism. But who will pay for it?

Newsrooms are shrinking, and Canadians are unwilling to open their wallets. The Public Policy Forum offers a way forward, funded in part by the federal government.

A reporter works on his story after Edward Greenspan, president and chief executive officer of the Public Policy Forum, held a news conference to release his report The Shattered Mirror, in Ottawa Thursday, January 26, 2017. (Fred Chartrand/CP)

Share

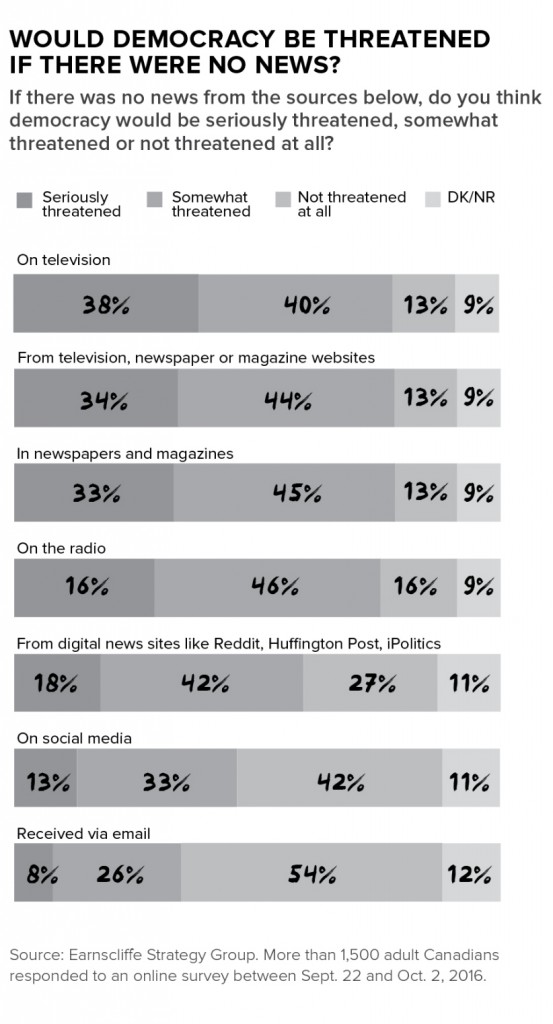

A sweeping report released Thursday by the Public Policy Forum offers a sobering picture of the hollowing-out of Canadian news media and a raft of recommendations aimed at shoring up the industry. But the report, ominously entitled “The Shattered Mirror,” also highlights a vexing conundrum: citizens express high levels of trust in media and the majority say “democracy would be seriously threatened” if the watchdogs disappeared—but they’re simply not willing to pay for it.

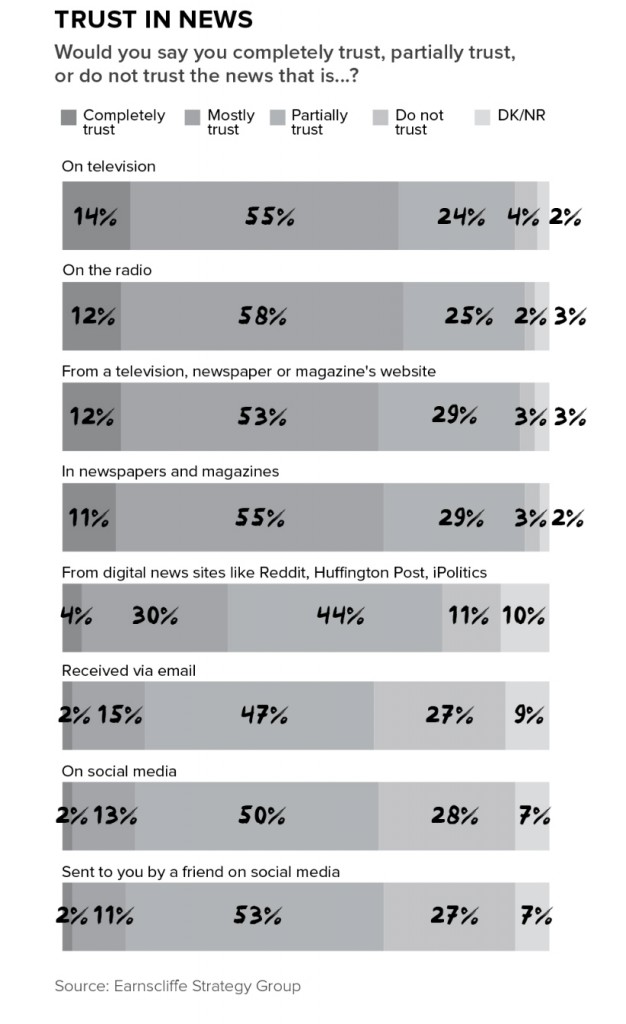

Edward Greenspon, president of the PPF and author of the report, said the focus groups and polling conducted by the Ottawa-based think tank revealed that people get most of their news from Facebook. But there is a key exception: if an issue is really important to them, people will seek out a familiar media outlet they know has reporters on the ground. “It’s not important on everything they interact with, but when it’s important to them, they want to have traditional media in place,” he said. “They trust traditional media more than they trust social media, and that is true of all ages of Canadians.”

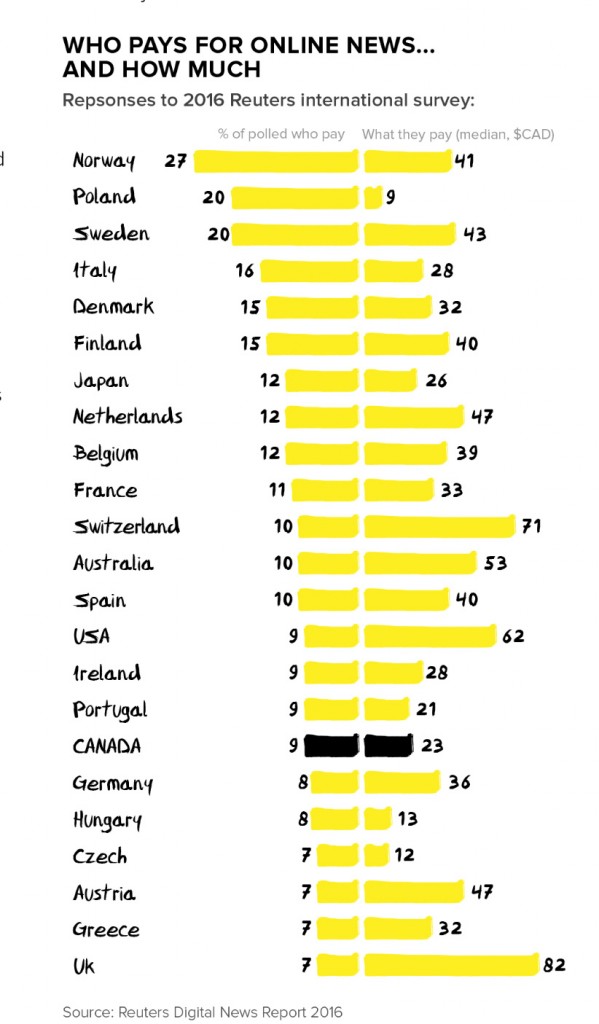

The huge “but” hanging over this is the fact that people are just not about to open their wallets, regardless of the value they assign to solid news coverage. A 2016 Reuters International survey cited in the report found that just nine per cent of Canadians pay for news; that’s in line with the United States but well below Norway’s 27 per cent and Poland and Sweden’s 20 per cent. “They feel badly that they’re not willing to pay,” said Greenspon, the former editor-in-chief of the Globe and Mail. “But they’re quite clear that this is a free marketplace, the culture of the marketplace has changed and they’re not going to foot the bill.”

The reason, in part, is that the public simply doesn’t perceive the media to be in financial difficulty. They see a deluge of more news from more sources delivered faster than they’re ever had access to before, Greenspon said, and it’s ferried to them on slick websites produced by seemingly robust media outlets. Readers see the ads papered on the websites they visit and figure media companies can just stop printing dead-tree editions, scoop up the money from their online ads and keep paying their journalists, he explained. The fact eludes them that digital ad revenue has only ever paid a fraction of the amount traditional print ads do. “The digital dimes-for-dollars argument is something the public doesn’t understand, nor should we expect them to understand that,” he said.

The centrepiece recommendation of the PPF report is a change to the Income Tax Act that would provide more incentive for advertisers to spend their money on Canadian media websites. As it stands now, advertisers can deduct the cost of placing ads only when those ads appear on Canadian broadcast and print media. However, this rule doesn’t extend to online advertising. The PPF report calls for this to change by creating a 10 per cent withholding tax on any online ad spending in media organizations that don’t qualify as Canadian.

That money collected from advertisers would be invested in a “Future of Journalism & Democracy Fund” that would support content creation and innovations in the industry. The report recommends an initial $100 million in start-up funding from the federal government, but beyond that, declares the fund should be self-sustaining with levy funds coming from the industry, estimated at $300 million to $400 million each year.

But the PPF’s extensive explanation around the independent, arms-length relationship of this fund to the government spotlights the inherent problem in having a watchdog industry supported—however obliquely—by the very hand it often needs to gnaw on in order to properly do its job. The think tank heard exactly that reluctance from the citizens it polled, and since the report was released, many journalists have voiced the same discomfort. “It’s our feeling that it’s not for the public to square that circle,” Greenspon said. “It’s for policy-makers to square the circle and design a system that allows for robust and independent digital-age media with lots of journalistic firepower, that is free and clear of government—as the news media should be.”