Chasing an Ebola vaccine

The race for the vaccine is less about stopping this epidemic than protecting against the next one

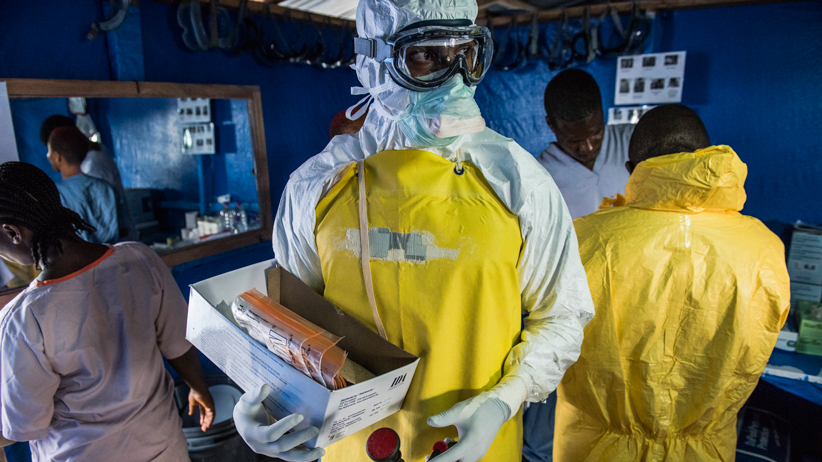

A health worker in protective gear carries empty blood sample kits at the Bong County Ebola treatment center in Suakoko, Liberia, Oct. 19, 2014. Because of the limited time they can spend in their stifling protective suits, the risks of certain procedures and even the amount of medicines available, doctors and nurses operate under constraints they often find frustrating. Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times/Redux

Share

In 2005, scientists working for the Public Health Agency of Canada reported a groundbreaking discovery: an experimental vaccine created in a Winnipeg laboratory had proven 100 per cent effective at protecting monkeys from Ebola. Three decades after the lethal virus was first identified in humans in central Africa, a potential remedy finally loomed. “This work is very interesting, very exciting and very promising,” one expert from the World Health Organization (WHO) said at the time. “There’s a long way to go before this vaccine could be put into people, but we really do hope it is pursued.”

Sadly, Big Pharma had no interest in such a pursuit. Ebola was still a relatively minor scourge, infecting barely 2,400 people since its discovery in 1976, and drug companies saw no profit in a potential vaccine—especially one destined for impoverished countries. By 2010, five years after that research made headlines, the federal government was so desperate to see its homegrown vaccine undergo human trials that Ottawa sold the licensing rights for a pittance ($205,000) to a small firm in Iowa: BioProtection Systems, a subsidiary of NewLink Genetics.

Once again, there was little movement on the file—until now. Ebola is suddenly priority No. 1 for global health officials, as they scramble to contain an unprecedented outbreak in West Africa that threatens to spiral out of control in 2015. At last count, the hemorrhagic fever has killed more than 6,000 people, and the WHO says it’s possible that 1.4 million will become infected by the end of January. Literally left on a shelf for almost a decade, that made-in-Canada vaccine now looms as a pharmaceutical godsend.

Known officially as rVSV-EBOV, the vaccine has been rushed through Phase 1 human trials (to test for possible side effects and to determine proper dosage), with plans to conduct more extensive tests on doctors and nurses working in the outbreak zone.

“Clearly, if those studies show that it’s effective in health care workers, the world would go into mass production,” says Dr. Gregory Taylor, Canada’s chief public health officer. Clinical trials are also under way on another potential vaccine, developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and licensed to GlaxoSmithKline, but experts are more optimistic about the Canadian version because it requires only one dose, while the other may need two (adding yet another hurdle to the challenge of vaccinating huge populations in a region with scant health care resources).

It’s possible, of course, that neither vaccine proves effective. What protects a monkey may not protect a human. And even if one version does excel during clinical trials, it may already be too late to stem the outbreak in any significant way; in a best-case scenario, it will take many more months—likely into 2016—to produce enough doses to vaccinate anyone beyond front-line health care workers. In truth, the mad sprint to find an effective vaccine is more about protecting against the next Ebola epidemic than stopping this one.

For the WHO, that disheartening reality only confirms what officials have been preaching for years: that Big Pharma’s drive for dollars is often at odds with greater public health. “A profit-driven industry does not invest in products for markets that cannot pay,” Dr. Margaret Chan, the WHO’s director-general, said in a scathing November speech. “The WHO has been trying to make this issue visible for ages. Now, people can see for themselves.”

Look no further than NewLink Genetics. A tiny biotech firm that has never brought a single product to market, the company now stands to be the biggest winner in 2015—after reselling the vaccine’s licensing rights to pharmaceutical giant Merck for a whopping US$50 million. Not bad for an initial investment of $205,000.

If only those millions had been invested years ago, when Canada’s vaccine first showed promise. The devastation still to come may have been preventable.