This Ontario town is trying to be Canada’s first carbon-neutral community

The tiny village of Eden Mills is closing in on its goal, proving what collective action can achieve

Zawadzki used green tech like solar panels and rainwater barrels for his new Eden Mills home (Photograph by Cole Garside)

Share

An hour’s drive from Toronto on the northwestern edge of Milton, Ont., is a little-known town with a little-known story of climate-change activism. With about 350 residents, Eden Mills has long sought to preserve its 19th-century charm, making it a haven for big-city escapees who enjoy cycling or placid walks along the Eramosa River. More recently, though, its inhabitants have worked toward a distinctly 21st-century goal: becoming Canada’s first carbon-neutral community.

The project has defined the past 12 years of Charles Simon’s life. He got the idea after watching a TV program about Ashton Hayes, which is aiming to become England’s first carbon-neutral village. It also happens to be located near where Simon, a retired engineer, grew up. After a summer visit to the U.K. in 2007, he returned to his own community with a vision. And to his surprise, his neighbours bought in.

READ: Climate change is making wildfires in Canada bigger, hotter and more dangerous

Other cities, provinces and entire countries currently grappling with climate crisis would love to be able to boast about Eden Mills’s results so far—at last count in 2013, the town was 75 per cent of the way to its goal of neutrality, thanks to an 18 per cent reduction in its carbon footprint and its abundant existing forest canopy that sucks up CO₂. Household emissions were down by 554 tonnes annually, while carbon sequestration resulting from greenery added by the community increased by 277 tonnes, or six per cent. (Preliminary results from a more recent count suggest the village is even closer, with the footprint down by 22 per cent.)

The enduring symbol of its achievements: the village’s 100-year-old community hall, a red-brick edifice whose carbon footprint has decreased by 96 per cent. Its need for purchased energy has dropped an astonishing 91 per cent annually since a massive retrofit involving everything from a solar-panel array to programmable thermostats.

Yes, it’s a success story writ small, say residents. And yes, it’s a lot easier to move the needle in a tiny community that doesn’t rely on industry. But Simon and others say it demonstrates the impact collective action at the grassroots level can have. “We were saying, ‘We are part of the problem, we can’t wait for government, we can’t wait for powerful corporations,’ ” he recalls of the genesis of the project. “We thought, if we start something from the ground up, other people maybe will follow and maybe we will learn something along the way.”

One of their earliest lessons was the virtue of starting small—a stratagem conservation campaigns in many larger communities overlook. For Eden Mills, it was the key to building a critical mass of support for more ambitious initiatives.

The project began with a core group of residents encouraging neighbours to take simple steps like switching to LED light bulbs and joining an annual drive to plant deciduous trees throughout the community. One couple, Les Zawadzki and Linda Henry, were about to build a new home in the village and embraced green technologies they’d learned about through the initiative—extra insulation under heated concrete floors; triple-glazed windows; a roof covered with solar panels; special aluminum tiles for heating water and collecting rainwater for landscaping.

READ: What climate change would mean for Canada’s famous landmarks

That build alone had a ripple effect, says Zawadzki, “because it introduced a few trades and local suppliers to greener technologies.” And the effect seemed to widen with each tree planted and window replaced. As word got out in the local press, supportive outsiders took interest and more locals got on board. With guidance from researchers at the University of Guelph, residents upgraded to energy-efficient heat pumps, while members of the Guelph/Eramosa Township council passed a resolution of support and installed signs at the town boundaries proclaiming the village’s goal of carbon-neutrality.

The galvanizing project, however, was the retrofit of the hall, which began in 2009. The five-year, $500,000 undertaking was funded by the Ontario Trillium Foundation, among a slew of other donors such as the Canada 150 Community Infrastructure Program, Farm Credit Canada, the Musagetes Foundation, the township of Guelph/Eramosa, and locals.

At that time, the hall’s annual CO₂ emissions totalled about 14,000 kg, roughly that of an average residential home. The overhaul started with heat conservation measures, including fully insulating the exterior walls and ceiling, replacing the windows and doors with energy-efficient units and installing those thermostats. It was completed in 2018, and today, thanks to the energy generated by its array of 10 kW solar panels, the hall’s carbon footprint is virtually zero.

The fixes have already begun paying for themselves. Simon figures powering the hall, with its myriad dances, suppers, wedding receptions and community meetings, would cost about $8,500 per year without the retrofits. Estimated net cost for energy this year: $1,400. Other stats point to successes that organizers hope other communities will imitate. Local people and outside volunteers have planted more than 40,000 trees. Between the carbon sequestered by increasing forest coverage and the overall reduction in emissions, Eden Mills is now within sight of its goal of absorbing as much carbon as it emits.

To be sure, challenges remain. Like most of the picturesque villages in Toronto’s shadow, it remains a car-and-truck town, and emissions from transportation accounted for a sizable portion of the village’s 4,621 tonnes in carbon emissions when they started the project. Changing driving habits won’t be easy. “Everything is so scattered, and biking can only help so far,” laments Richard Lay, an engineer who has advised the village in the field of sustainable building design.

Mike Schreiner, the leader of the provincial Green Party, notes that rural communities struggle to make the transition to electric vehicles because there are so few charging stations in outlying areas. Eden Mills “should be honoured and celebrated,” says Schreiner, MPP for Guelph and his party’s first representative in the Ontario legislature, “but you also see where that can run up against public policy decisions around land use planning and how communities are designed.”

READ: Yes, climate change can be beaten by 2050. Here’s how.

None of which, of course, lies within the control of Eden Mills’s residents—though the utopian-sounding notion that it does is discernible among them. Lay, one of the project’s earliest supporters, speaks lyrically of a period when he first arrived here in the 1970s: “I used to swim in the pond and bicycle the pretty roads,” he says, gazing across the calm river from his living room. “The underlying driver behind economic degradation is population growth and our basic economic system that says you have to exploit the world’s natural resources in order to make the people in control wealthy.”

Nor can Eden Mills exert much influence on the current drift of the climate debate, which in Canada increasingly centres on the toxic issues of carbon taxes and pipelines. As consensus grows among activists and environmentally minded politicians that only carbon pricing can make a dent in emissions, conservation initiatives like theirs seem to be falling out of favour.

The thing about idealism, though, is that it sustains you through adversity. So the Eden Mills carbon-fighters have carried on, many of them inspired by developments such as the success of young Democrats in the United States in getting the Green New Deal, an economic stimulus package that would address climate change, before the House of Representatives. Or the Ontario NDP proposing net-zero emissions for the province by 2050 and cutting emissions in half over the next decade.

READ: The climate crisis: These are Canada’s worst-case scenarios

The historic election of Schreiner last year lifted their spirits, too, as he’s a believer in the ability of green power to transform the economy. He’s quick to point to Eden Mills as Exhibit A. “They’ve been able to, one, create jobs by retrofitting their buildings; two, save money, because they’re spending less on energy,” he says. “Then that’s money that circulates in the local economy, creating local jobs and local benefits.”

Not all of those benefits can be totted up in emissions reductions or loonies saved, notes resident Linda Sword, another early proponent of the project. What began years ago as an opportunity “to take action and not despair,” she says, gave identity and common cause to a community that now has reason to shout its name to the rest of Canada—indeed the rest of the world—and encourage others to follow.

“This has taught me about celebration,” she says. “This community celebrates everything—every little accomplishment, it doesn’t matter how small. And it celebrates together. It’s a wonderful way to live.”

This article appears in print in the August 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Within reach of Eden.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

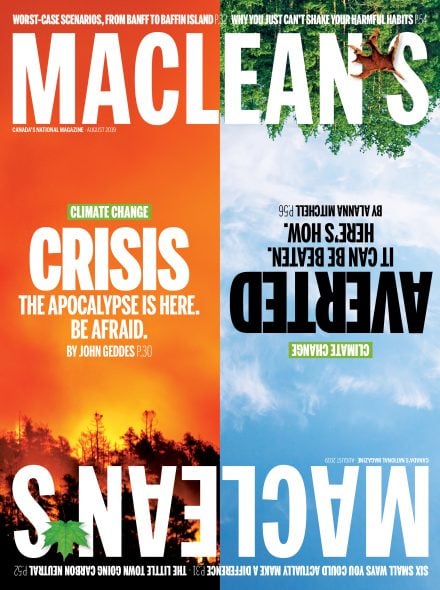

This article is part of a special climate change issue in advance of the federal election. This collection of stories offers a comprehensive look at where Canada currently stands, what could be done to address the issue and what the consequences might be if this country continues with half measures. Learn more about why we’re doing this.