Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou: The world’s most wanted woman

Inside the high-stakes extradition fight for a top Huawei executive—and why Canada’s relationship with China may never recover

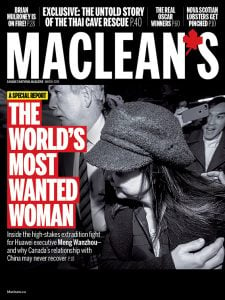

Huawei chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou leaves a Vancouver courthouse on Jan. 29, 2019. (Darryl Dyck/CP)

Share

For about $11,000 Canadian, a first-class ticket on Cathay Pacific from Hong Kong to Vancouver entitles the purchaser to a “suite” with a seat that transforms into a bed, wood-panel finishes, an organic cotton sleep suit and, if one pleases, a flute of champagne and a tin of caviar to begin dinner service. The Dec. 1 overnight trip was smooth and speedy, arriving at the Vancouver gate at 11:17 a.m., 18 minutes ahead of schedule. Meng Wanzhou couldn’t have known it at the time, but this early touchdown would shorten her remaining time as a free woman.

The snaking, glass-wall-lined corridor through Vancouver’s international terminal let Meng loosen her weary legs as she headed toward the customs area. She was scheduled for a 12-hour layover before catching a red-eye to business meetings in Mexico City. But after she scanned her Hong Kong passport in the self-serve machine, border authorities flagged her for further screening.

Two days earlier, U.S. officials had caught wind of Meng’s stopover in Vancouver—because her flight from Hong Kong crossed U.S. airspace, Homeland Security had its passenger list, and by Nov. 30, a B.C. Supreme Court judge had signed a provisional warrant for the Huawei chief financial officer’s arrest under the Extradition Act, due to looming U.S. charges against her for fraud linked to violating international sanctions against trade with Iran. RCMP officers awaited her arrival.

Meng was escorted to a windowless room for questioning by federal authorities. The 46-year-old’s severe hypertension flared up, so after the interrogation, she was taken to a nearby hospital for treatment. Then authorities took her to the Alouette Correctional Centre for Women in Maple Ridge, B.C., one hour’s drive from the airport and worlds removed from the luxuries familiar to a member of Chinese corporate royalty.

This would set off a cascade of events that now traps Canada between two antagonistic superpowers—one helmed by a man obsessed with demonstrating that he always holds the strongest hand despite a feeble grasp of the state of play, the other by a leader determined to prove that his country could rocket to worldwide economic dominance without the encumbrances of Western democracy.

Meng’s arrest would lead, in dizzyingly short order, to the imprisonment of two Canadians in China for reasons deliberately kept murky, and the resentencing of a third to death after his original 15-year prison term was suddenly deemed inadequate. Any pretense of friendly bilateral relations imploded as Chinese officials publicly scolded, mocked, insulted and threatened, and Canada leaned on its allies for support, with the implication that next time it could be them.

As China demanded that Canada pick a side, it would become glaringly obvious that the U.S.—the closest of this country’s allies by dint of both geography and long precedent—was more interested in nabbing Meng and Huawei than any repercussions Canada might face as a result. Equally apparent was that Ottawa had been caught flat-footed, seemingly unprepared for the forces Meng’s arrest would unleash. At the centre of the saga stood Huawei, telecom behemoth, striving avatar of China’s global ambition and—many critics charge—an instrument of state surveillance whose tentacles reach far beyond China’s borders. Meng would spend months out on bail, swathed in luxurious semi-confinement in her Vancouver home, surrounded by neighbours who barely knew her, occasionally sending plaintive and oddly hammy PR missives to the outside world.

Through the ratcheting international tensions, Canadian politicians and government officials would return again and again to the phrases that are supposed to lay out how things work—rule of law, international order, apolitical process—as though by repeating these words like a mantra, they will suddenly matter again. Instead, the blunt fury with which Beijing reacted to the arrest of one of its most prized and prominent citizens would make that belief look like starry-eyed naïveté.

READ: Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou’s arrest: What you need to know

The whole affair threatens to demolish Canada’s carefully built relationship with China, with enormous consequences. China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner, with total trade between the countries growing from $11 billion in 2001 to $64.4 billion in 2016. Eleven per cent of recent immigrants to Canada are from China, making it the third-largest source of new Canadians behind India and the Philippines. Almost a third of Canada’s 500,000 international students—who contribute more than $15 billion to the economy annually—are Chinese.

These numbers reflect Ottawa’s long-held hopes of closer ties with the world’s fastest-growing economy. The Meng saga would not so much sour that burgeoning relationship as make plain the profoundly corroded ground on which it was destined to rest. Xi Jinping’s China had dropped its mask.

***

Well before the bail hearing, the extradition request, the long list of U.S. indictments, the arbitrary detentions and death sentence for Canadian citizens and the furious diplomatic exchanges, there had been hope of something much more amiable between Ottawa and Beijing.

If there was a high point in relations between Justin Trudeau’s government and Xi’s Chinese regime, it may have lasted for a little less than five minutes on March 19, 2017, when John McCallum presented his credentials to Xi as Canada’s new ambassador.

The meeting was short, but at least Xi hadn’t made the new guy wait long. McCallum—a perpetually rumpled former bank economist who had held senior cabinet portfolios under Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin and Trudeau—had been in Beijing less than 24 hours. His appointment was part of a full-court Trudeau strategy to deploy top talent to deal with an increasingly complex modern world. Chrystia Freeland was the new foreign minister, tasked with keeping Donald Trump calm. Stéphane Dion would be Trudeau’s emissary to Brexit-tossed Europe. And McCallum, whose wife, Nancy Lim, is Chinese, and who speaks a kind of halting, nice-try Mandarin, was tasked with fulfilling the dream of generations of Canadian political leaders: a special and deeply lucrative relationship with China.

Later, McCallum told the Toronto Star his message to Xi had been that Canada wanted a deeper alliance than any previous leader on either side had envisaged. “My slogan is more, more, more. We want to do more trade, more investment, more tourists, more co-operation in many areas.” And back in Canada, Huawei, an increasingly visible global brand, seemed to be fulfilling that vision, wooing consumers through flashy sponsorship deals with institutions like Hockey Night in Canada, while making inroads in the country’s telecommunications infrastructure and research institutions.

McCallum’s arrival in Beijing kicked off nearly a year of talks between Chinese and Canadian officials on the scope of a possible free-trade agreement. But already that project was doomed. Because already, China was changing in ways that would make closer co-operation on any terms except Xi’s impossible.

He’d become general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission on Nov. 15, 2012, and consolidated his leadership role by launching a major anti-corruption campaign, recalls Guy Saint-Jacques, Canadian ambassador to Beijing from 2012-16, in an interview. Xi swore he’d go after “tigers and flies”—party figures high and low—but it’s a funny thing: though there were thousands of arrests, “no one close to him was arrested for corruption,” Saint-Jacques says.

With his leadership role consolidated, Xi set about making the CCP “an effective Leninist instrument of control,” a report from the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service said. The May 2018 report summarized the discussions at a conference the intelligence agency organized a few months earlier, gathering academics and think-tank specialists from around the world. “Xi Jinping is driving a multi-dimensional strategy to lift China to global dominance,” the report states. “This strategy integrates aggressive diplomacy, asymmetrical economic agreements, technological innovation, as well as escalating military expenditures.”

This new assertiveness amounted to a total abandonment of the cowed, wary stance China adopted internationally under Deng Xiaoping, its leader through the 1980s, who summed his strategy up as “hide your strength and bide your time.”

There was a limit to how much China could hide. World Bank figures show the country’s gross domestic product was US$347 billion in 1989; by 2012, the figure had grown to $8.6 trillion. (It has grown by nearly 50 per cent since even that relatively recent date.)

Xi used the 19th National Congress of the CCP in October 2017 to announce that China’s bashful era was over. He set a 30-year goal to re-establish China as the world’s leading power. “For a long time, [China] appeared to fear the West much more than the other way around,” the CSIS report states. “This is no longer the case.” Indeed, under Xi, it is “persistent in disputing the global rules put in place by powers it perceives as in decline.”

Few companies symbolize Xi’s strategy as clearly as an upstart telecom launched by a former engineer from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). It was Meng’s father, Ren Zhengfei, who founded Huawei in 1987, and back when Meng was a high school student using the photocopiers at the company’s Shenzhen office for her exam papers, the company was just one of many in China jostling for contracts to modernize the country’s telecommunications infrastructure.

Detractors point to Ren’s PLA career as evidence of the company’s ties to the communist government. But Dan Breznitz, the Munk chair of innovation studies at the University of Toronto, says Huawei got less help from the state and military in its early days than most people assume. Huawei “does not see itself as a creature created by Beijing,” he says. “It sees itself and its whole story and culture as . . . very independent.”

But Ren did take notes from a foundational figure of the People’s Republic. Inspired by Mao Zedong’s strategy of guerrilla warfare, Huawei dispatched sales staff to China’s rural areas first, gaining market share in areas overlooked by other companies. By the time its competitors noticed the company had emerged as a serious threat, it had already built up a solid base of business.

Meng first worked at Huawei in 1993 as a receptionist, but her career began in earnest when she returned in 1997 after completing her master’s degree in accounting. (Recent reports that she dropped out of high school appear to result from the mistranslation of an interview.) By that point, Huawei was a major domestic telecom player, with its sights set on global expansion. It took on the rest of the world the same way it took on China: by selling high-quality equipment at an affordable price to overlooked developing countries first, only tackling the First World after establishing market share elsewhere. To do that, Huawei had to be aggressive, willing to bend rules while working with some of the world’s more unsavoury regimes.

This aggressive corporate culture rocketed Huawei into the Fortune 500 in 2010, with the company overtaking Sweden’s Ericsson as the world’s largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment in 2012. It also created a long and growing list of lawsuits, controversies and investigations. In 2001, Indian newspapers reported Huawei had developed telecommunications equipment for the Taliban in Afghanistan, which the company denied and Indian authorities never corroborated. An Algerian court convicted a Huawei executive and two others from another Chinese telecom giant, ZTE, of bribery in 2012. The year before that, the Wall Street Journal reported that Huawei had become Iran’s leading telecommunications provider.

Huawei apparently realized it needed to do something about its image problem, and Meng was tapped to be its kinder, gentler public face. In 2013, she started hosting media briefings on financial results and even answered questions about her family and personal life, disclosing that her father—now CEO and a member of the board of directors—owns 1.4 per cent of the company. She said Huawei “has no secrets,” despite the lack of publicly available details (it is an employee-owned collective, a structure that is a holdover from the days when private companies were illegal in China, which makes its shareholder structure opaque). “We already have a plan to choose a time to turn the ‘black hole’ into total transparency,” Meng said in the full speech, which Maclean’s had translated. “My father said that if you tell a lie you will have to tell 10 lies to cover up the first lie. Ordinary people like us must tell the truth.”

When asked why her surname is different from her father’s, Meng said she changed it to her mother’s maiden name when she was 16, but did not give any reason for doing so.

Two weeks later, a Reuters story alleged she had been busy doing some less public-facing work for Huawei. The news wire had previously reported a Hong Kong-based company called Skycom had offered to sell at least $2 million worth of equipment made by American company Hewlett-Packard to Iranian company Mobile Telecommunication Co., in violation of U.S. sanctions. The proposal included at least 13 pages marked “Huawei confidential” with Huawei’s logo.

READ: U.S. alleges Huawei stole secrets, evaded Iran sanctions

The second Reuters report found more links between Huawei, Skycom and Canicula Holdings, the company that held Skycom’s shares. The article revealed Meng served on Skycom’s board from 2008 to 2009 and was Canicula’s company secretary in 2007. Huawei called the link between Huawei and Skycom “a normal business partnership” and asserted that it complied with international law.

In August 2013, Meng was trying to convince the U.S. bank HSBC that the reports about Huawei’s connections to Skycom were nothing to worry about. In a PowerPoint presentation that would be filed by the defence as an exhibit in B.C. court after she was arrested, she described Skycom as a “business partner” and Huawei’s relationship with it as one of “co-operation,” not control. Relying on her assurances, HSBC decided to continue as Huawei’s banker.

A year later, at an annual Huawei conference for finance professionals in New York, Meng took the stage to lavishly praise her American hosts and outline her company’s relationship with the U.S. She opened her speech by saying it was no accident that the U.S. was the birthplace of the internet and the hub of technological advancement. “These achievements can be attributed to the idealism and dedication of the American people and the advanced, flexible systems of the U.S., and more importantly to the American culture, in which individuals are respected, innovations encouraged, failures tolerated and intellectual property rights protected,” she said. “Huawei’s success today is the result of continuous learning from the U.S.”

Indeed, the company currently leads the global race to build the next generation of data networks, known as 5G. But already, three of Canada’s allies in the “Five Eyes” intelligence network—the U.S., New Zealand and Australia—have banned Huawei from their 5G infrastructure. The U.S. is leaning hard on the two holdouts, Canada and Britain, to do the same.

READ: What’s the worst China could do with access to Canada’s 5G network?

The American case against Meng would assert that her PowerPoint assurances to HSBC were lies that led to banks clearing hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of transactions that may have violated economic sanctions. Those transactions represent a tiny fraction of the US$92.55 billion the company reported in revenue in 2017, meaning that if the allegations are true, Huawei seemingly took an enormous risk for relatively little gain.

But Timothy Heath, a senior international defence researcher at the RAND Corporation who has also worked as a China specialist with the U.S. government and military, said the business aspects may be beside the point. Iran is an important Chinese ally, he notes, and Huawei is not the first Chinese company to be accused of violating sanctions there: “I can see the Chinese government wanting to demonstrate to Iran that they are a reliable partner and friend, finding ways to discreetly provide support. Using someone like Huawei is the perfect vehicle for doing that.”

***

Canadian government officials say there was no political coordination between Washington and Ottawa—not even a courtesy heads-up for Trudeau—before the gears of the official extradition process began turning on Nov. 30. A New York court issued the warrant for Meng’s arrest last Aug. 22, but Trudeau first learned of what would be his biggest diplomatic headache more than three months later in Argentina. On Nov. 29, he landed in Buenos Aires for events scheduled around the annual summit of the Group of 20 nations. He must have expected the trip’s most memorable moment to be the planned Nov. 30 signing of the new NAFTA trade agreement at the Palacio Duhau hotel. Instead, that same day, his top aides briefed him on developments in Ottawa: the Canadian Department of Justice’s International Assistance Group had received a formal request for Meng’s arrest from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of International Affairs.

Justice officials had quickly grasped the sensitivity of the request, senior government sources say, and alerted their counterparts at Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and in the Privy Council Office. Even with top politicians and their aides in the loop, however, federal officials say the process unfolded exactly as it would in less sensitive cases. The Justice Department issued what’s called an “authority to arrest,” which allowed lawyers working for the RCMP to seek an arrest warrant from a B.C. judge.

On Dec. 1, Trump and Xi—also in Buenos Aires for the G20 summit—had a private dinner meeting during which the two talked themselves down from the ledge of a trade war, at least temporarily. It was, in Trump’s telling, “an amazing and productive meeting with unlimited possibilities for both the United States and China.” By the time the two men cut into their grilled sirloin, Meng had been taken into RCMP custody.

News of her arrest didn’t hit the public radar until Dec. 5, when her appearance at the courthouse in Vancouver attracted a sparse crowd. A Vancouver Sun reporter observed the tech executive in a prison-issued dark-green tracksuit, smiling and nodding to male spectators in business attire, as a Mandarin interpreter sat at her side. And once Meng’s arrest went public, the Chinese embassy in Ottawa wasted no time demanding that Canada “immediately correct the wrongdoing” and release her.

In a conference call with reporters on Dec. 7, Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland said Canada’s envoy to China, the former Liberal MP and cabinet veteran McCallum, had briefed Chinese officials about Meng’s case. She declined to comment when asked about suggestions raised in the media by China observers that Beijing might strike back by detaining Canadians.

Meng was back in court that day in Vancouver, and this time, she was awaited by several dozen Canadian and international journalists, along with a large coterie of Chinese and Huawei representatives, plus interested locals. Her hearing was moved to the $7.2-million Courtroom 20, built for 2003’s Air India bombing trial, a cavernous space with a 149-seat public gallery separated from the proceedings by two layers of bulletproof glass.

The court lifted a publication ban on the Americans’ fraud allegations against Meng, which the Crown laid out to the judge. Meng’s lead defence lawyer, David Martin, gave a preview of her potential fight against the charges and extradition case: Huawei’s actions were in strict legal compliance, he said, and the suggestion that a PowerPoint presentation “induced the Hong Kong bank, the largest financial institution in the world, with vast compliance departments . . . to continue to provide financial services is preposterous.”

Questioning why the U.S. wasn’t levying a stronger sanctions-violation case against Huawei, like the battle Washington waged against Chinese tech giant ZTE, Martin hinted at a political subtext. “As matters unfold in the United States, there’s been an increase in velocity of conflict,” he told the court. “But I shouldn’t speculate about that.”

Indeed, the hearing wasn’t about whether the accusations held water. It was about whether or not Huawei’s CFO should spend the next several weeks or months in jail as she awaited an extradition hearing. John Gibb-Carsley, the Canadian government lawyer acting on behalf of the United States, argued that Meng’s wealth and connections were so vast that “no amount of bail or surety” could keep her from fleeing once free from prison. He also suggested Meng had no meaningful connection to the Lower Mainland, and that her intent to flee was made clearer because she and fellow Huawei executives had avoided travel to the United States since spring 2017, when a grand jury subpoena likely made Huawei aware of the criminal investigation.

Martin maintained his client has strong connections to Vancouver—a six-bedroom house purchased in 2009, in her husband’s name, along with a much larger house acquired in the city’s elite Shaughnessy neighbourhood, undergoing renovations for her family’s future stays. Meng stated in an affidavit that she spends at least two to three weeks of summer in the city every year, and the defence released photographs of her posing with relatives and friends by landmarks like the Lions Gate Bridge and the legislature in Victoria.

Further, Martin said Meng’s personal dignity would prevent her from breaching a court order. “To do so would be to humiliate and embarrass her father, whom she loves,” the lawyer said. “It would humiliate and embarrass the Huawei employees and the institution as a whole . . . and given her prominence in China, she would not embarrass China itself.”

Martin also explained Meng’s many health problems: chronic high blood pressure, 2011 surgery for thyroid cancer, and last May’s surgery for sleep apnea, which still made eating solid foods a challenge. “I continue to feel unwell and I am worried about my health deteriorating while I am incarcerated,” Meng said in her affidavit. Despite her precarious health, she had scheduled a whirlwind business trip for the very days she ended up in court: Mexico City to Costa Rica, then to Argentina, France and back to China, spending only a couple days in each city.

As Meng’s hearing stretched into the following week, a modest clutch of Chinese-Canadians gathered to demonstrate in support of her release. Joe Luo, clad in a plum-coloured blazer, printed out small “We love you Huawei” posters for others to carry. He used to be an engineer for Nortel Networks, he said, so he knows Huawei is “a great company, founded by great people in a great country.” “And stop doing the dirty work!” he shouted to assembled TV cameras. “For who?” he was asked, and he lowered his voice near a whisper: “For Americans.”

One day, near the start of proceedings in Courtroom 20, someone’s cellphone blared March of the Volunteers, the Chinese national anthem. Meng’s husband, Xiaozong Liu, sat in the front row as lawyers clashed over his viability as a guarantor for her bail as a non-resident of Canada visiting on a six-month visa.

Martin laid out details of his bail proposal, including the $15 million Meng would post, mostly comprised of equity in her family’s two Vancouver houses. As part of a complex plan to assure the court that Meng would stay put if granted bail, her lawyers had lined up an Ontario company that monitors bail suspects through electronic ankle bracelets, and Lions Gate Risk Management Group, a security firm that would provide guards and technological surveillance.

The judge wanted another day to consider his bail decision, and that night, Meng’s lawyers touched base with several individuals in her small local social network. On Dec. 11, Martin presented the court with a new set of Vancouverites who would help guarantee Meng’s bail compliance. It was a foursome that seemed drawn from a 9:30 a.m. lineup at a Vancouver Starbucks: a realtor, an insurance agent, a wealthy homemaker and a part-time yoga instructor—all Meng acquaintances in some way.

Justice William Ehrcke concluded that given several attestations to her character, and the fact that she’s “a well-educated businesswoman who has no criminal record,” bail should be set at $7 million in cash from Meng and her husband plus $3 million in sureties from her friends, with Meng footing the bill for the security monitoring. Applause rang out from the other side of the thick glass courtroom partition, and a smiling Meng gave a thumbs-up to the public gallery, then hugged her lawyers, pausing to wipe away tears.

***

On the other side of the globe in Beijing, McCallum had received an unusual Saturday summons from China’s vice-minister of foreign affairs, Le Yucheng, who wanted to personally express China’s anger over Meng’s arrest. He called it “unreasonable, unconscionable and vile in nature,” and warned there would be “grave consequences” if Canada did not immediately free the Huawei executive. After that, it was the American ambassador’s turn to be summoned to hear demands for the U.S. to drop its request to Canada.

Late on the eve of Justice Ehrcke’s bail decision, that sabre-rattling turned into action for a former Canadian diplomat named Michael Kovrig. He was working as a Hong Kong-based analyst for the International Crisis Group (ICG), an NGO that describes itself as conducting field research and offering policy recommendations “to help end deadly conflicts worldwide.” Kovrig had previously worked at the Canadian embassy in Beijing, specializing in detailed reporting on political issues—a job that required extensive travel in China to places most foreigners don’t visit, such as Tibetan minority areas, and meeting with dissidents. “All this was to take the pulse of China and try to find out what was going on,” says Saint-Jacques, the former ambassador, who worked closely with him.

Kovrig, who holds a master’s degree in international affairs from Columbia University, produced analysis that was balanced and thorough, Saint-Jacques adds, which ensured his work was well-received in Ottawa. Kovrig was quiet by nature, but at the end of each work week, he always joined his embassy colleagues to play ball hockey on some nearby tennis courts. In addition to his work in Beijing, he helped the consulate general in Hong Kong handle Trudeau’s September 2016 visit.

He liked China so much that he wanted to stay on at the end of his term rather than return to Ottawa for more training, so Saint-Jacques offered some advice. “I said, ‘Go ahead, apply for a leave without pay, but I certainly hope that after a few years you will want to come back to the department because we need people with your skills and your competencies,’ ” the former ambassador remembers.

Kovrig, who is in his late 40s, joined ICG in February 2017 as senior adviser for northeast Asia. The organization is well-known and highly regarded by GAC; Freeland had been scheduled to address its annual awards dinner at New York’s swanky Mandarin Oriental hotel on Oct. 3, but she cancelled when the updated NAFTA agreement was finalized just a few days before.

While working for ICG, Kovrig was unafraid to speak his mind publicly. A few months after he started his new job, when China’s state-run news agency Xinhua talked about Xi’s charisma fostering a love of China, Kovrig tweeted: “Saying it don’t make it so. Dear Xinhua, this is what soft power looks like.” Attached was a photo of Trudeau on the cover of Rolling Stone with the headline “Justin Trudeau: Why can’t he be our president?”

And this past October, as the China-U.S. trade war escalated, Kovrig told CNBC, “[Donald Trump] may also be attempting to put more pressure on China on multiple fronts in order to gain negotiating leverage on trade. If so, this kind of linkage between issues is a risky tactic that could backfire by deepening the rift between the U.S. and China.”

The remark was darkly prophetic. Although Kovrig was based in Hong Kong, he frequently visited Beijing to meet Chinese officials or attend conferences. But on Dec. 10, he wasn’t in Beijing for business, but rather for a personal trip. It was cut short when the State Security Bureau picked him up on the street near the apartment where he was staying.

A few hours later, in the middle of the night, ICG’s president Rob Malley was awoken by an emergency phone call to his hotel room. A friend of Kovrig’s had contacted the group’s office in Brussels, which tracked down Malley in Tokyo. “At first, you hope it’s a mistake or that they just want to ask him a few questions,” Malley says, “but of course we know the broader context of what’s happening between China and Canada.”

Back in Washington the day after Kovrig was picked up, a reporter asked Trump if he would intervene in Meng’s case with the Justice Department. The response was a jaw-dropper even by the current administration’s standard of caprice. “If I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made—which is a very important thing—what’s good for national security, I would certainly intervene if I thought it was necessary,” Trump said.

Freeland found out about Trump’s remarks much as the rest of the world hears about utterances from the White House: through a news report on her phone. The following day, in a press conference just off Parliament Hill, she offered two lengthy, excruciatingly careful answers to questions about Trump’s apparent politicization of the file, defending the impartiality of Canada’s process. “I do also think,” Freeland finally got around to saying, “that it is incumbent upon parties making an extradition request to be sure that extradition request is about ensuring that justice is done—is about respecting the rule of law. And our extradition partners should not seek to politicize the extradition process, or use it for ends other than the pursuit of justice and following the rule of law.”

During that news conference, Ottawa journalists learned that a second Canadian had apparently been detained by Chinese officials. When Freeland was asked about reports of another missing Canadian, she offered a glimpse into the shadows-and-fog quality of sorting out what’s happening in China. “We were in touch with a person who was being asked some questions by Chinese authorities,” Freeland said, “and we have not since that moment been able to ascertain the whereabouts of that person.”

The second Canadian to apparently pay the price for Meng’s arrest was Michael Spavor.

He had achieved a surreal sort of notoriety in 2013, when he helped arrange for former NBA player Dennis Rodman to visit his “friend for life,” North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un. Spavor grew up near Calgary; his fascination with the Hermit Kingdom was sparked during a visit to Seoul in the late 1990s, when he came across a chapter on North Korea in a Lonely Planet guide. “Just a little sliver in the back,” Spavor told Maclean’s in a 2013 profile. “It was the most interesting part of the whole book.”

He eventually spent six months in Pyongyang in 2005 as a teacher with a Canadian NGO. After his return to Canada, he worked as a continuing education instructor in the ESL program at the University of Calgary. In a blog post, he shared a photo of himself and his students in Pyongyang, laughing uproariously in front of Canadian and North Korean flags. “I can’t remember why we are laughing, but the guy on my right was always making funny jokes,” Spavor captioned it.

After moving back to Asia years later and working in various tourism and non-profit sectors in South Korea, Spavor became director of the Pyongyang Project, a Canadian non-profit meant to engage with the people of North Korea. By 2013, he could speak the North Korean dialect well enough to fool people on the phone, and when Rodman wanted to make a return visit to North Korea—his first had been arranged by a documentary crew—someone put him in touch with Spavor as one of the few people on the planet who could make it happen. In a photo apparently taken around the time of that visit, Spavor and Kim lean companionably toward each other. The caption says the two were enjoying Long Island iced teas aboard the North Korean leader’s private yacht.

In 2015, Spavor founded the Paektu Cultural Exchange, which organizes sport, business and tourist excursions to North Korea “to promote greater peace, friendship and understanding.”

Spavor—in his mid-40s—was living in Dandong, a northeastern Chinese city that looks across the Yalu River to North Korea. He remained resolutely apolitical about the North Korean regime. “I’m really in no position to comment on political and human rights issues,” he told Maclean’s in 2013. “Those issues are better discussed between governments.”

His work didn’t go unnoticed in China, and he was at one point detained for a few days for questioning. “More of a ‘Who are you and what are you doing’ kinda thing,” Spavor’s friend Leo Jehn, who owns a restaurant in Seoul, recalls. “He was doing something unique, so they were curious and I guess wanted to let him know he was being watched.”

On Dec. 9, Spavor took to Twitter to announce some travel plans. “BACK IN SEOUL! I’ll be in Seoul from Monday the 10th for a few days for new consulting work :) yeah! And a few meetings. I’ll be busy but if you want to have a few Makgeoli’s or beers with some of my friends come out…” he tweeted at 4:13 p.m., misspelling makgeolli, a popular Korean alcoholic beverage.

On Facebook, Spavor tagged a bunch of friends to gather them for a party once he arrived in Seoul. It’s unclear when and where he was picked up by Chinese authorities, but he never made it to that gathering. After Jehn realized what had happened to Spavor, he tried to look back at the Facebook Messenger history in which he and his friend had talked about his trip to Seoul, but the messages had been deleted. The two follow each other on Instagram, too, and the social-media site showed recently that someone had signed into Spavor’s account—six weeks after he was locked up.

It is grimly unsurprising to Saint-Jacques that the Chinese targeted Kovrig and Spavor, who would both eventually be accused of endangering national security. China’s national security law, adopted in 2015, is sweeping and general by design, he says, a net constructed in such a way that it can scoop up anyone. Spavor would have been an obvious target because of his uncommon access to North Korea, a territory over which China is protective; the very skills and experience that made Kovrig so valued at the embassy would have made him similarly suspect. “When you’re a diplomat in China and you speak Mandarin, you are a potential spy,” Saint-Jacques says. “And because he travelled to remote areas, I’m sure he was on the radar.”

The walls have eyes and ears in China, Saint-Jacques says—cameras and facial-recognition software are everywhere—and locals who meet with foreigners may be required to helpfully debrief their government on the conversation afterwards. He is convinced the Chinese maintain lists of carefully watched foreigners of various nationalities—a sort of human catalogue of bargaining chips at the ready. “If a problem occurs with a country of this foreigner, they will just nab him either to try to use this person to do a swap, or to try to punish,” he says. “For foreigners who travel to China or live in China, they have to keep that in mind. You could be a target at some point.”

On Dec. 14—unusually soon by the standards of Chinese detention—McCallum was allowed to meet with Kovrig. Two days later, he met with Spavor. When Canadian officials are allowed to visit—generally once a month, as laid out in Canada’s consular agreement with China—they get just 30 minutes. So consular staff would have met in advance to go over the key information they needed to obtain from Kovrig and Spavor. “You want obviously to make the best use of the time, so you will ask questions about how is the person, what kind of pressure he or she is under,” Saint-Jacques says. The locations where people are detained are kept secret, so Canadian officials would be taken to another designated spot for the meeting. “It’s very short, it’s controlled,” says Saint-Jacques.

Following these first visits with Kovrig and Spavor, GAC was publicly tight-lipped, merely confirming the meetings and vowing to continue to work with the detained men and their families, but offering no details on their condition or treatment.

Behind the scenes, though, there was a coordinated push from Canadian officials at all levels. TheToronto Star reported that in response to Trump’s musings about striking some kind of trade deal with China involving Meng, Trudeau asked the U.S. president to ensure that any such agreement would include freeing the two detained Canadians. Other Canadian officials pressed that point with their American counterparts as well, according to the report.

***

Huawei, meanwhile, was stepping up its PR campaign, publishing on its corporate website what it said was a Dec. 19 excerpt from Meng’s diary. Meng wrote that during her bail hearing, “many strangers” had called her lawyer offering their own property to cover her bond; these people did not know her personally, she said, but knew Huawei and wanted to help. “My lawyer said that in his 40 years of professional career he had never seen anything like this,” she marvelled.

The executive also said she had received a WeChat message from a Japanese stranger, the serendipitous arrival of which prompted Meng to share a long meditation on Huawei’s efforts to assist after the Fukushima earthquake. “I rarely mention this experience, and I have nothing to be proud of. It’s just my job. As they say, ‘Good people will be rewarded for what they do,’ ” she wrote. She added, “When I read the words of the Japanese citizen, I could not help bursting into tears, not for myself, but for so many people who believe and trust me.”

The diplomatic mess over Meng’s arrest was dominating the Liberal government’s attention as Parliament broke for the year-end holiday. On Dec. 21, Trudeau met in his offices across Wellington Street from Parliament with the top federal figures on Chinese issues—including Freeland, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan and Chief of Defence Staff Jonathan Vance.

That meeting marked a shift toward a more high-intensity Canadian push to persuade allies to take public aim at China over the detentions. “We are deeply concerned by the arbitrary detention by Chinese authorities of two Canadians earlier this month and call for their immediate release,” Freeland said in a statement released later that day. “I wish to express Canada’s appreciation to those who have spoken recently in support of the rule of law as fundamental to free societies.” The next day, in a conference call with journalists, she said Canada’s ambassadors would be asking for support in a campaign to put pressure on Beijing.

At that point, the U.S., Britain and the European Union had already voiced support for Canada. On Christmas Eve, China snapped back. “What’s this got to do with Britain and the EU?” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying asked. “When the Canadians illegally detained a senior executive at a Chinese company at the request of the United States, where were they?”

But Trudeau and Freeland kept chalking up statements of support, or noting when they had raised the issue in conversations with their counterparts in other countries. By mid-January, Trudeau talked about China with six heads of government—among them Trump, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and German Chancellor Angela Merkel—plus European Council President Donald Tusk and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. His officials tallied public statements of support from 11 countries, including Australia, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Latvia and Spain.

GAC, meanwhile, adjusted its travel advisory for China, urging Canadians to use “increased caution” because of “arbitrary enforcement of local laws.”

China seemed less daunted than defiant. In fact, the lengthening list of mostly Western nations critical of Beijing’s seizing of the Canadians seemed to prompt some innovations in the Xi regime’s rhetoric. On Jan. 9, Lu Shaye, China’s ambassador in Ottawa, wrote an extraordinary op-ed in the Hill Times, accusing his country’s critics of a “double standard” in their refusal to see Meng’s arrest and the detentions of Kovrig and Spavor in the same light. “The reason why some people are used to arrogantly adopting double standards is due to Western egotism and white supremacy,” Lu wrote. In a press conference, he also threatened “consequences” if Canada banned Huawei from its 5G network.

In Beijing, Canadian consular officials were permitted second meetings with both Kovrig and Spavor, but then China abruptly tightened the screws in deadly fashion on a third imprisoned Canadian.

Robert Lloyd Schellenberg, an oil field worker originally from Abbotsford, B.C., arrived in China in November 2014 while travelling across southeast Asia. He’d left behind in Canada convictions for drug offences, and a B.C. judge in 2012 had noted that Schellenberg’s father “had turned his back on him because of his criminal history,” though other family members stood by him.

Once in China, Schellenberg was introduced to a translator through a mutual friend. The translator, Schellenberg said, turned out to be part of a drug-trafficking syndicate. “I am not a drug smuggler. I came to China as a tourist,” Schellenberg said recently in a Chinese courtroom, according to Agence France-Presse.

Within weeks of his arrival, Schellenberg tried to depart for Thailand, at which point he was arrested, according to Chinese media. Prosecutors said he was hiding more than 200 kg of crystal meth in car tires, with a plan to ship the drugs out of the eastern Chinese port city of Dalian to Australia.

Schellenberg’s first trial stretched over two and a half years, and he was sentenced in November 2018 to 15 years in prison. But at his appeal hearing in late December, prosecutors said more evidence had surfaced that proved he was involved in the smuggling operation, which made his sentence insufficiently harsh, so a retrial was ordered. Foreign media were invited to watch-—a rare occurrence in Chinese courtrooms, and a move that seemed designed to ensure the proceedings grabbed international attention. In a one-day trial on Jan. 14, he was convicted and sentenced to death.

“Worst-case fear confirmed,” Schellenberg’s aunt, Lauri Nelson-Jones, told media. Freeland slammed Schellenberg’s sentence as “inhumane and inappropriate,” while Trudeau voiced the “extreme concern” of Canada and its broad coalition of “international friends and allies.”

Then, near the end of January, while speaking to Chinese-language media in his former riding of Markham-Thornhill in Toronto, McCallum made heads explode across Ottawa when he made the baffling decision to publicly lay out the case for Meng’s fight against extradition. “I think she has quite good arguments on her side,” he said. “One, political involvement by comments from Donald Trump in her case. Two, there’s an extraterritorial aspect to her case. And three, there’s the issue of Iran sanctions in her case, and Canada does not sign on to these. So I think she has some strong arguments she can make before a judge.” McCallum attempted to walk back the comments the next day, saying he “misspoke.”

RELATED: Meng, McCallum and the worst foreign policy bungle in a generation

Through the entire affair, federal government officials had been at pains to emphasize again and again—to both the Americans and the Chinese, depending on who seemed to need to hear it most—the absence of political meddling in Meng’s case in rule-of-law Canada. Trudeau’s response to questions about McCallum’s extemporaneous musings echoed that. “We will ensure, as a government and as a country, that all the rules and the independence of our justice system is properly defended and properly supported,” he said.

The day after McCallum issued his mea culpa, he told a StarMetro reporter that it would be “great for Canada” if the U.S. were to drop its extradition request. Whether it was because McCallum had the wrong idea or because he had the right idea but said it in his outside voice, Trudeau had had enough; under pressure from the Conservatives, he asked for and received the ambassador’s resignation. The PMO statement announcing his ouster included plenty of praise for McCallum’s two decades of service as a cabinet minister, but nary a word explaining his canning. Two days later, Freeland said McCallum had to go because his comments were inconsistent with the government’s position that Meng’s case is a judicial one free of political meddling.

In fact, the process is by no means that clear-cut. Under Canada’s Extradition Act, Meng’s arrest started a clock ticking, giving American authorities 60 days—until Jan. 30, 2019—to make a formal extradition request, including evidence mustered against her (they did so one day before the deadline). Then the Canadian Justice Department has until March 1 to issue what’s called an “authority to proceed.” Assuming the Justice Department issues that within the 30-day period, an extradition hearing before the B.C. Supreme Court will be scheduled. And if the court decides Meng should be “committed” for extradition, the justice minister—not a judge—decides whether to actually surrender her to the Americans. The process can stretch on for months or years.

In a press conference carried live on CNN two days before the extradition request deadline, the Americans slammed the door on any hope Canada had that it might wriggle out of this trap. The U.S. Department of Justice unsealed a 13-count indictment against Huawei, including charges of bank fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy to commit fraud against Meng.

“It’s important to understand that Ms. Meng has been charged based upon her own personal conduct and not because of actions or misconduct by other Huawei employees,” said Richard Donoghue, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York. Acting U.S. Attorney General Matthew Whitaker added that the Americans were “deeply grateful to the government of Canada for its assistance and steadfast commitment to the rule of law.”

***

Through this whole affair, there has been a vocal school of thought—counting among its members former foreign affairs minister John Manley, who told CBC that Canada should have displayed “a little bit of creative incompetence” at YVR—that a sharper Canadian government would have found a way out of its current position, wedged between two warring giants.

Tourism companies that arrange trips between Canada and China in both directions have reported a drop in business, and a Nanos poll conducted for the Globe and Mail in early January found that 56 per cent of Canadians think Meng’s arrest is “primarily a justice issue” and that Canada did the right thing. However, 29 per cent of Canadians align with Beijing’s views, believing the arrest was politically and economically motivated. Eight in 10 Canadians have a negative view of China’s one-party system, the poll found, and 53 per cent see China as a threat to Canada’s national security.

As for the federal government’s views, what seems clear is that at some point between Trudeau’s late-2017 visit to Beijing and now, the thinking about China—what was possible in terms of trade and general friendliness, what the moral and democratic costs of that would be and whether it was worth it—changed. McCallum—and others in the Ottawa orbit—seem to have missed the memo, perhaps because none was issued. Even now, in the midst of an international uproar in which three Canadian lives hang in the balance, there is little clarity on the federal government’s thinking about China.

There is, however, no shortage of analysis available to inform such thinking, and it does not paint a reassuring picture. “China has not emerged as a benign and benevolent beast,” writes Jonathan Manthorpe in a fascinating new book, Claws of the Panda: Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada. “Far from it. It has all the hallmarks of a fascist regime, if one accepts the definition of fascism as being a country with a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader, severe economic and social regimentation and forcible suppression of the opposition.”

Manthorpe is a veteran foreign correspondent whose previous postings include Hong Kong, and Claws of the Panda will become the definitive guidebook for understanding the Canada-China relationship. The idea—advanced by the late Pierre Trudeau, among others—that an open China would inevitably adjust its political, business and social practices to fit with international norms has been a resounding failure, he writes.

When the last great China optimist, Jean Chrétien, was elected, Canada still had a larger GDP than China. Now China’s is larger than Canada’s by a factor of 10, and Canada has fallen from being China’s fourth-largest trading partner in 1970 to its 21st-largest in 2016.

The elder Trudeau’s opening of diplomatic relations signalled an end to Western isolation of Mao in 1970. Chrétien’s first Team Canada trade trip to Beijing in 1994 ended a second stage of isolation after the Tiananmen Square massacre. “Canada had served its purpose,” Manthorpe writes.

He does not call for anything resembling an end to Canada-China relations, but Manthorpe argues “Canadian politicians need to assume a much tougher and more self-assured attitude toward Beijing.” Pushing back isn’t futile, he writes: “The party and its operatives are often off-balance when dealing with established democratic societies.”

Lu, the ambassador in Ottawa, has warned Canada off engaging in “microphone diplomacy” over the imprisoned Canadians, and insisted, for instance, that the World Economic Forum was not the place to agitate for further international support. “We hope the Canadian side will think twice before acting,” he said.

Freeland ignored this when she went to Davos near the end of January, making the rounds of high-level officials from Italy, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Jordan, Romania and Ukraine to “highlight Canada’s deep concerns regarding China’s actions against Canadian citizens and to thank those partners who have spoken up in defence of the rule of law and against arbitrary detentions and the death penalty.”

China has repeatedly dismissed the idea of other countries standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Canada as irrelevant and counterproductive. But of course, hollering that someone should stop doing something is an odd way to demonstrate that you don’t care about it. “Xi Jinping is a very proud individual. They want to project the image that they have made it, but this is bad publicity,” says Saint-Jacques. “Previously, when they were punishing a country and nobody else would react, they were sending the message to others: ‘Don’t mess with us because we will do the same thing with you.’ Now, I hope that this early solidarity will continue.”

Meng, meanwhile, has been living a comfortable, if carefully monitored, life on bail. She has travel privileges across roughly 250 sq. km, including Vancouver, much of Richmond and the North Shore. She must steer clear of the airport, be accompanied out by her court-ordered security minders and be at home between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., unless her bail supervisor permits otherwise.

She has one specific appointment every week, six kilometres from home. It’s a trip to the federal probation office in a Burrard Street plaza above an insurance office and Hawaiian poke restaurant, across the street from a Ferrari and Maserati dealership. On one of these recent visits, Meng wore an Hermès scarf and carried a woven leather handbag by the Italian luxury brand Bottega Veneta.

But it appears she spends most of her time at home, where guards keep watch around the clock on eight-hour shifts, and she regularly receives guests and gifts. One overcast Friday morning in January, movers from a Richmond home design store parked a truck at Meng’s curbside as they moved furniture in. Otherwise, it was a quiet scene, one of waiting—a former police officer standing in her front yard, drivers in a pair of hulking black SUVs across the street, someone else in a Toyota SUV by her rear lane’s garage. Inside the tall-fenced backyard stood a green portable toilet for the use of Meng’s minders.

Shortly before noon, after the furniture truck was gone, a black Suburban pulled up and deposited two women carrying stuffed plastic bags from T&T Supermarket. They registered with a clipboard-toting guard, and a man exited the house to help the women with their bags.

While Meng has been living in a gilded fishbowl surrounded by the comforts of home, only the most shadowy information is known about where the three Canadians are and how they are being treated. Schellenberg is awaiting a response to the death-sentence appeal he was required under Chinese law to write himself, while Kovrig and Spavor are interrogated for hours each day and kept in cells where the lights blaze and they are supervised around the clock. Everything they say during questioning is recorded, and they have been forced to hand over the passwords to their social-media accounts.

When consular officials are permitted a monthly visit with the detained men, they’re forbidden to speak French so that Chinese authorities can monitor their conversations. Consular staff gather medications and books, letters and photos from worried families to pass along at these visits, knowing that guards will scrutinize them for hidden messages.

The lights, the limitations, and especially the uncertainty—the entire process is designed to ratchet up the psychological pressure bearing down on the imprisoned Canadians, while Beijing applies a parallel order of stress to Canada in the realm of international relations.

There is an inescapable feeling that no one involved will be sprung from their trap until Meng goes free.

—with files from Terry Glavin