In their honour, we publish their names

Maclean’s has published more than 66,000 covers, each one dedicated to an individual Canadian who died in the First World War

The statue known as Mother Canada looks out over Vimy Ridge as part of the memorial commemorating Canadian war losses near Arras, France. (Tom Stoddart/Getty Images)

Share

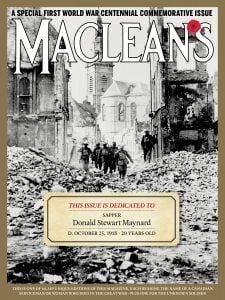

If you hold a paper version of Maclean’s, consider closing this issue for a moment to read the dedication on the cover. You’ll find the name of a Canadian serviceman or woman whose life was snuffed out more than a century ago in what became known as the “Great War.”

Where possible, we also list their rank, age and date of death. But even such tombstone details for thousands of soldiers were lost in the chaos of war or the mists of time. This compounds the tragedy of Canada’s deadliest war, for surely we owe them this: respect for their courage, and remembrance for their ultimate sacrifice; lessons written in blood and, as history shows, too easily forgotten.

And so, you hold a name.

There are 66,349 unique issues of this magazine; 66,349 different covers, each dedicated to one of the “fallen,” that bloodless term for bodies torn apart by bullet and bomb, poisoned by gas, or ravaged by infection. The names of people, distinct and irreplaceable, who never returned from the killing fields to realize their potential in a young country still finding its place in the world.

Sixty-six thousand, three hundred and forty-nine names—and one “Unknown,” representing all the soldiers, some 20,000 never accounted for; buried in forgotten graves, or sucked deep into the mud of Flanders, or obliterated by the destructive power of weaponry never before seen in battle.

MORE: Search our database of Canadians who died in the First World War

What’s in a name?

“We are the dead,” wrote Lt.-Col. John McCrae of Montreal as he gazed at the fresh grave of his friend Lt. Alexis Hannum Helmer, 22, killed by a bomb on May 2, 1915, near the French-Belgium border. McCrae enlisted as a medical officer in 1914. “I am really rather afraid,” he admitted to a friend, “but more afraid to stay at home with my conscience.”

McCrae, too, would die, age 45, succumbing to pneumonia and meningitis on Jan. 8, 1918, ravaged in body and spirit while tending the endless parade of the damaged and the dying. In Flanders Fields, his poetic lament, endures—though the peace he craved did not.

Perhaps your magazine is dedicated to Nursing Sister Agnes Florien Forneri of Kingston, Ont. She shuttled between military hospitals in London and France, the strain destroying her health. She died of a hemorrhage from a stomach ulcer, April 24, 1918—one of 44 Canadian women who died in service that year.

Statistically, most of the dead Canadians were young infantrymen. People like Pte. Elmer Arthur Dahmer of Galt (now Cambridge), Ont., just 18 when he enlisted in 1916. He survived Vimy Ridge, only to die Aug. 8. 1918, the first day of Canada’s final 100-day offensive that contributed mightily to Germany’s defeat.

RELATED: 100 years ago, Canadians led the First World War’s final charge

Victories were no longer measured in yards of mud, but in miles of terrain as Canadian troops, under Canadian command, rose from the trenches, using stealth, speed and superior intelligence to surge under a “creeping barrage” of withering artillery fire.

The place names—Amiens, the Drocourt-Quéant line, the Canal du Nord, Valenciennes—may not resonate as Vimy does, but the capture, one-by-one, of these strongholds helped force Germany’s unconditional surrender.

And finally, on the 100th day, near Mons, Belgium, Pte. George Lawrence Price, 25, of Port Williams, N.S., was the last Canadian soldier to die in combat. A sniper’s bullet tore into his heart just two minutes before the Armistice came into effect on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, 1918.

It was a cruel end to a bloody war. Almost 46,000 soldiers of the Canadian Corps were killed, wounded or taken prisoner in those 100 days.

“Do you understand the nature and terms of your engagement?” asked the military induction form. Price would have written “yes,” as Dahmer did. As they all did.

But how does one understand the incomprehensible? Infantrymen suffered an extraordinary 80 per cent of Canadian casualties. And yet they fought.

READ J.L. GRANATSTEIN’S ESSAY: How Canada earned the world’s respect

Most entered the war as civilians. They were farmworkers, like Price, and shopkeepers, teachers and doctors. They were as green as the country they sailed from. A British officer training fresh-off-the-boat Canadians in riflery bellowed in despair: “Gentlemen, when I see you handle your rifles I feel like falling on my knees and thanking God we’ve got a navy.”

And yet, by the war’s end, Canadian soldiers were considered elite shock troops, their reputation forged at terrible cost. It wasn’t until Easter of 1917 that the four divisions of the Canada Corps fought as a unified force to storm the seemingly impregnable Vimy Ridge. While the capture of Vimy, which had eluded the British and the French, was of limited strategic value, it looms in the Canadian imagination as a keystone of nationhood.

“They had been gassed at Ypres and bloodied on the Somme,” wrote Pierre Berton, historian, author and former Maclean’s managing editor, in his searing examination of the battle, “and the shoulder badge ‘Canada’ had made them all brothers, no matter what their language or region.”

Back home, the mounting toll left no corner of a country of just eight million untouched by tragedy. In cities and whistle stops, Canadians mourned together, a family united in grief and pride.

READ MORE: What Vimy means, a century after the iconic battle

There is a term military command used to describe the loss of soldiers from battle for whatever reason. They called it “wastage.” It is ugly, but certainly more straightforward than “the fallen.” Night falls. Leaves fall. Soldiers bleed and soldiers die.

Their names are inscribed in cenotaphs, on plaques and in legion halls across the country, and in the battlefields of Europe. They live, too, in the yellowed pages of scrapbooks in homes across Canada, hauled out on rare occasions by distant relatives to acquaint themselves with missing branches of the family tree. And to wonder what might have been.

Consider a young medical officer wounded by shrapnel in the war’s closing days and sent home with a Military Cross. Capt. Frederick Banting, as he was then, lived to become, three years after the Armistice, a co-discoverer of insulin. How many Bantings, in any number of endeavours, did we lose? Wastage indeed.

Those of a certain age will recall Remembrance Day ceremonies long past where the ones who made it home, faded, frail and bent with age, pinned on medals and poppies inspired by McCrae’s poem. They joined their dwindling corps of comrades to recall what most of us can only imagine.

Those who could stand, stood straighter. Those who could march, marched. While others hunched and shivered through the silence and the reveille, these old ones seemed impervious to the November cold, having known far worse.

The war followed too many of them home, haunting their dreams and draining joy from their waking hours. They called it nerves or fatigue or shell shock, as we now call it post-traumatic stress disorder. They tried to forget what we strain to remember.

Across the Atlantic is the towering Vimy memorial on a pockmarked patch of Canadian soil in France, justifiably immodest in scale. Its two massive pylons, cut from 6,000 tonnes of limestone, soar above the countryside.

The design came to Canadian sculptor Walter Allward in a dream. “I saw thousands marching to the aid of our armies,” he explained. “They were the dead.” Inscribed there are the names of 11,285 Canadians, those killed in France with no known resting place.

He sculpted outsized allegorical statues to represent in human form such principles as faith, truth, honour, sacrifice—and loss. The largest of these is a cloaked woman, stooped in mourning; Mother Canada as she came to be known.

Allward searched for an appropriate model, finding his muse in British-born Edna Alice Jennings. Her shoulders were broad and strong, her niece Rosemarie Biggs of Edmonton later explained. “He said ‘Mother Canada had a huge burden to carry.’ ”

As do we. Their names live on in the remembering. We shoulder their burden as guardians of peace.

CORRECTION, Oct. 19, 2018: An earlier version of this post misstated the timing of the Armistice that ended the First World War.