A bizarre grow-op odyssey comes to an end

Authorities couldn’t believe a real estate magnate had no idea his building housed a mammoth grow-op

Tobin Grimshaw/CP

Share

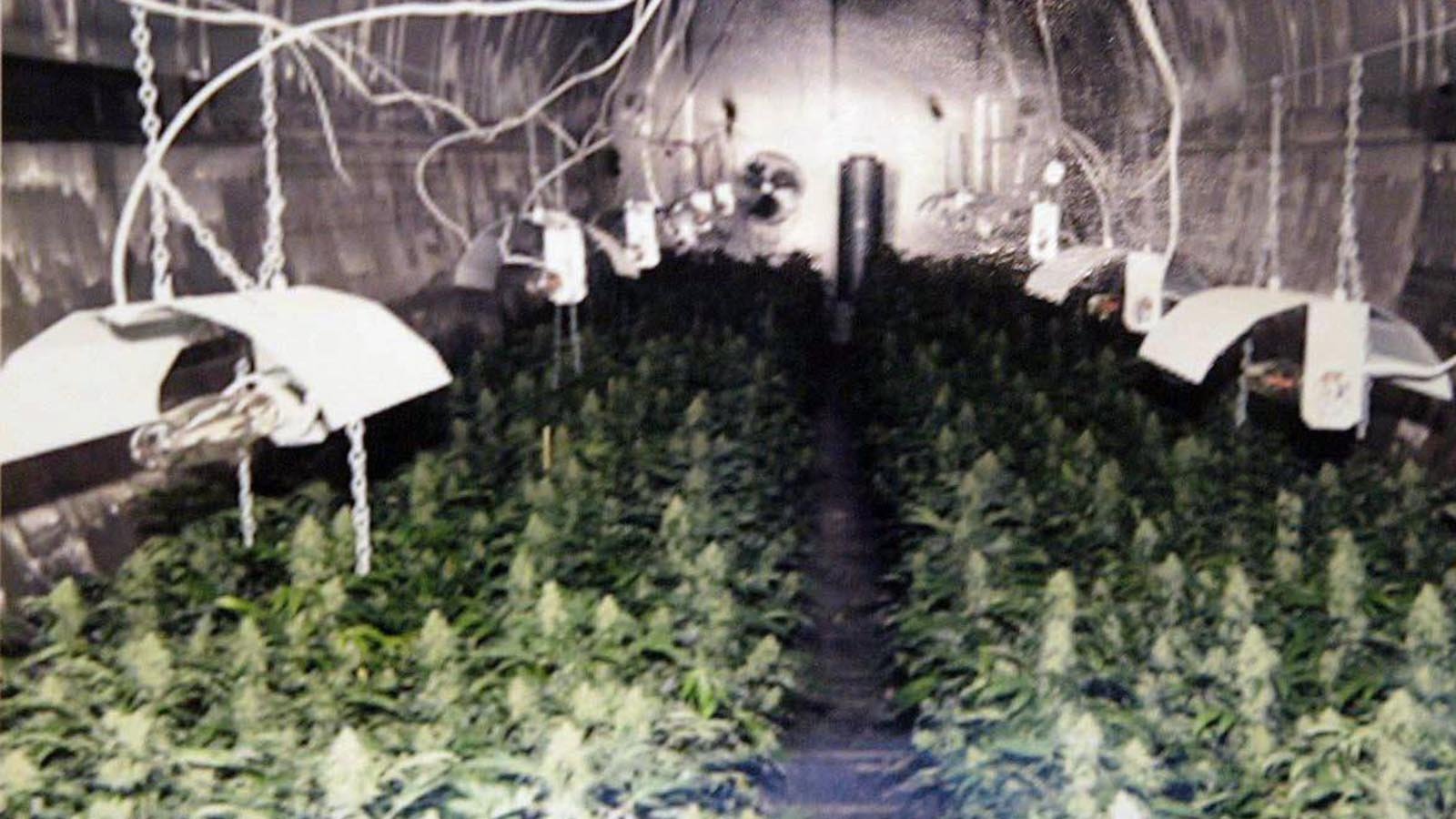

Ten years later, it remains one of the most legendary drug busts in Canadian criminal history: a sophisticated, multi-million-dollar marijuana grow-op hidden behind the walls of a former Molson brewery in Barrie, Ont. When police raided the old factory in January 2004, they discovered a literal jungle of high-grade pot plants, including thousands of green leaves budding inside the same gigantic beer vats that once produced some of the country’s favourite ales. As one senior officer said at the time: “You had to see it to believe it.”

For nearly two years, nobody saw it. Not the cops. Not the countless Highway 400 commuters who drove right past the building every day on their way to and from Toronto. Not even the other tenants who rented space in the once-booming brewery—and who were neighbours to a mammoth underworld enterprise. The operation was so discreet, so disciplined, the “employees” rarely left, sleeping in dorm-style accommodations complete with kitchens, laundry and a games room.

There was one other person who insisted he had no clue what was going on: Vincent DeRosa, a wealthy Toronto real estate magnate whose company, Fercan Developments, owned the now-infamous factory. As unbelievable as it may sound, DeRosa told investigators he was completely oblivious to the humongous weed harvest inside his brewery.

Although police did conduct an exhaustive probe—charging nearly two dozen people, including DeRosa’s older brother, Robert, who managed the Barrie property—Vincent was never implicated. But the state did pursue him in civil court, trying (twice) to seize the brewery under proceeds-of-crime legislation. Maintaining his innocence, DeRosa repeatedly fought back and, last week—a decade after the original bust made headlines—he won what appears to be the final legal battle, convincing a judge not to freeze more than $4 million from a recent sale of the land.

“There is no evidence before me to show that Mr. DeRosa had any knowledge of, or participation in, the marijuana grow operation,” wrote Madam Justice Mary Vallee, in a ruling released April 23. To freeze the $4- million sale proceeds, pending a forfeiture hearing, “would be manifestly harsh and draconian” and “offend the community’s sense of fairness,” she concluded.

For Brian Greenspan, DeRosa’s long-time lawyer, it’s a bittersweet victory. Authorities didn’t have any evidence to lay criminal charges in the first place, he said, so they found another way to target his client. “I think, quite frankly, they looked at it simplistically and unrealistically,” Greenspan says. “The government said: ‘This was the largest grow operation that we’ve known about. How could the owner not have known?’ ”

Federal prosecutors took the first crack at DeRosa’s building, slapping a restraining order on the property in 2010 and arguing that the land should be forfeited pursuant to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Under that federal law, the Crown had to prove Fercan was complicit in the illegal activity occurring at the factory in order to seize it.

They failed—utterly. After a seven-week hearing last year, Justice Peter West said the evidence was “overwhelming” that DeRosa had no idea his brother had gone behind his back and helped launch a huge marijuana plantation. (In fact, when Robert pleaded guilty in 2011 and received a 6½-year prison term, he specifically apologized to Vincent. “He did not know about the grow operation,” Robert told the court. “I’m sorry for the trouble I’ve caused.”) West’s ruling lifted the restraining order on the brewery and appeared to mark the end of the grow-op odyssey.

But when the land was sold in September 2013 (pursuant to power of sale proceedings), Ontario’s attorney general filed its own claim, arguing DeRosa’s cut of the transaction—exactly $4,067,685.10—was “proceeds of an unlawful activity” and should be frozen, pending a hearing under the provincial Civil Remedies Act. Greenspan was stunned. “This was nothing more than a collateral attack on the earlier judgment,” he says. “I’ve been 40 years at the bar, and I’ve seldom, if ever, been more offended by a government action. There should be some thoughtful decision-making applied as to whether or not you proceed against someone who so clearly and unequivocally has been exonerated.”

Justice Vallee was not quite so critical, but, in the end, she did agree with the defence. “To date, no credible evidence of wrongdoing on Mr. DeRosa’s part has been provided in a Canadian court,” she wrote. “Based on the record before me, I conclude that the interests of justice would not be served by preserving the funds from the sale of the property.” The Crown has until May 5 to release the $4 million to Fercan Developments.

Greenspan says DeRosa, now 52, is “finally relieved that, at the end of the day, the decision-making process operated fairly.” And that hefty cheque he’s about to receive after all these years? “He is not dependent on that money for his next move,” Greenspan says. “But he will certainly make it part of some business or investment, whether it’s real estate or some other venture. He is a high-calibre businessman who has done very, very well.”