Canada now brings in more refugees than the U.S.

For the first time in the history of the United Nations refugee program, the U.S. has slipped behind another country.

Syrian refugee family Mohammad Al Mnajer and wife Fouzia Al Hashish sit with their three daughters Judy, second left, Jaidaa, far right, and Baylasan as they eat their after school snack at their home in Mississauga, Ont., Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Share

Canada’s status as a global leader in refugee resettlement—new figures show it has eclipsed the U.S. in the number of refugees it brings in—owes less to Canadian generosity than a cool disinterest from a neighbouring administration.

Robert Falconer, a Calgary-based researcher, had been following Washington’s retrenchment from refugee assistance under President Donald Trump out of both professional and personal interest: his father landed in Edmonton as a refugee after fleeing Augusto Pinochet’s 1970s dictatorship in Chile. Falconer wondered whether the U.S. refugee intake had begun to fall towards Canadian levels, which were lower than the height of 2016’s Syrian resettlement program but higher than recent years. But when he collected the figures, he was surprised. “I didn’t realize how drastic the change was,” says Falconer, who’s with the University of Calgary School of Public Policy.

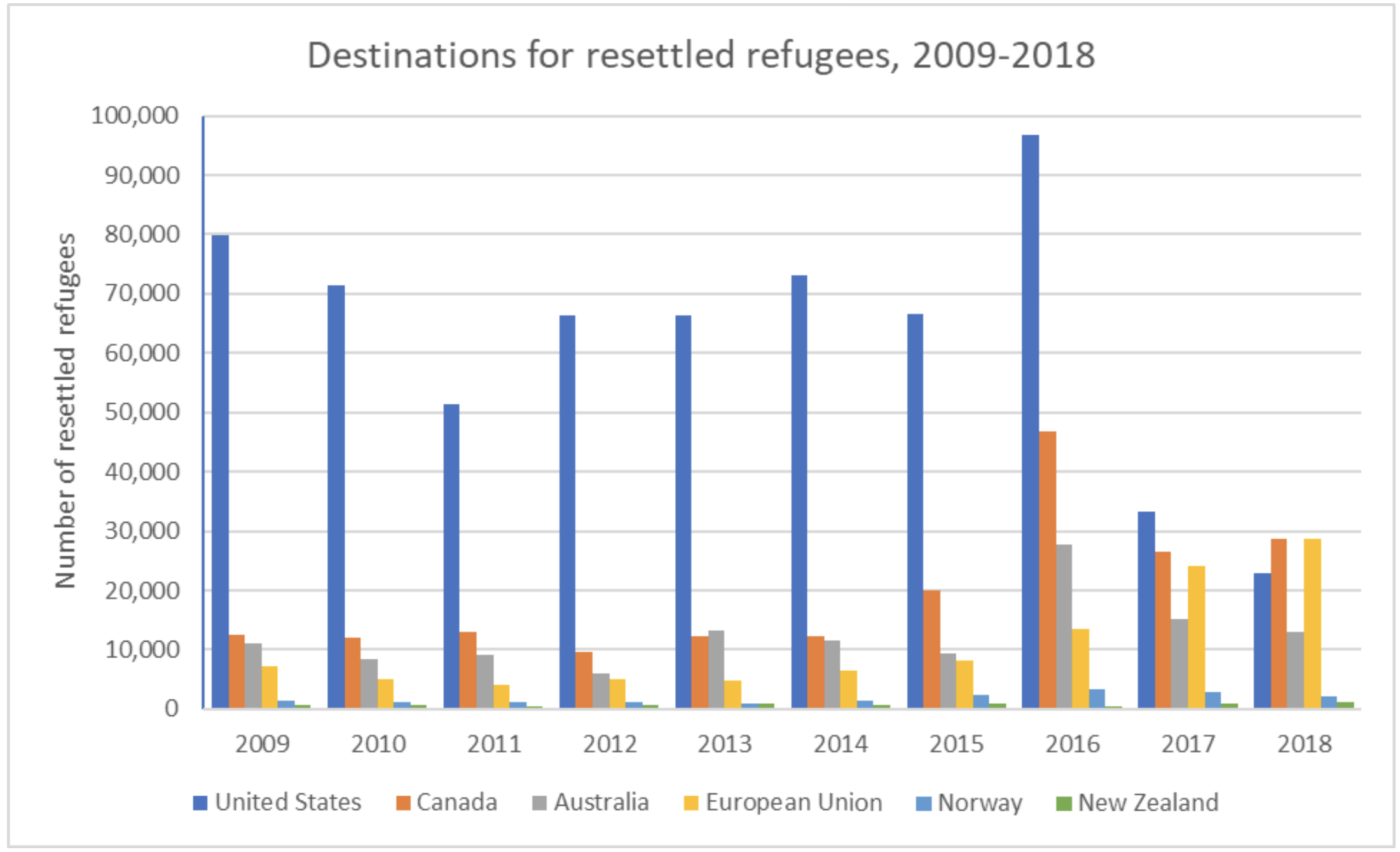

The United States took in 24,000 refugees through the global refugee program last year and Canada accepted 28,000. This marks the first time that United States slipped behind another country in the history of the United Nations refugee program, which began in 1946 in the grim shadow of the Second World War. Canada’s resettled refugees are about double what the country took in earlier this decade, while the American levels are less than one-third of what they recently were, and the lowest in any year since 1977, according to the U.S. State Department.

The American plunge came a year after Trump demanded a freeze in the refugee program to study further vetting, a pledge made at the same time as he banned travellers from seven countries, most of them with Muslim majorities. Refugees entering the United States now face an “enhanced” vetting program.

Resettled refugees are in a system separate from asylum seekers, such as the ones who have walked across the border along the Quebec-New York border. While asylum seekers find their way into Canada and try their refugee claims before tribunals, resettled refugees have their cases and urgency vetted overseas, often in refugee camps, in concert with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

The decline of the U.S. refugee program behind Canada’s comes at a time when the refugee crisis worldwide has reached unprecedented levels, with strife in Myanmar, Syria, Sudan and elsewhere. There are more than 25 million refugees worldwide, and annual resettlement is down to 102,800 worldwide, according to the UNHCR. “This gap between the number of refugees in need of resettlement and the number we actually resettle has grown substantially,” Falconer says. Canada has remained consistent in its acceptance of resettled refugees amid the Trump retrenchment and shifting moods in Europe, which has taken in vastly more asylum seekers in recent years than it has refugees through resettlement programs, though last year the European Union took in almost as many of those migrants as Canada did. Some European countries like Germany and United Kingdom aim to increase their resettlement levels as they tighten their acceptance of asylum claimants, while others like Hungary and Denmark are becoming less welcoming to desperate newcomers altogether, Falconer says.

Becoming the top resettler of refugees likely won’t mean to Canada what it did to its neighbour. The United States would take the lead in urging other countries to join the program, and help negotiate their refugee levels. Canada likely lacks the comparable diplomatic or economic clout to take on that task, Falconer suggests. But what it could do, he says, is promote its thriving sponsorship program, through which individuals and private groups like churches take the initiative of settling refugees in Canada, as opposed to the government-assisted program.

Canada also has capacity to accept more refugees to make up for the U.S. decline, even as the country’s asylum intake rises as well, the University of Calgary researcher says. The combined total is nowhere near European levels, but as the asylum processing and hearing backlog grows, along with costs to government, public confidence and willingness to take any sort of refugee may wane, Falconer says. “It may be easy for researchers to divide resettled refugees from asylum seekers from economic immigrants, people who come to reunite with family, but it isn’t so conveniently divided in public perception,” he says.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has set a target of 29,950 resettled refugees in 2019. Falconer predicts the U.S. intake will fall further. There’s little sense it will recover as long as Trump is in the White House, to the detriment of thousands of people in refugee camps worldwide.