Shafia ‘honour killers’ do not deserve a new trial: Crown

Why Mohammad Shafia’s own words may sink his case for a retrial

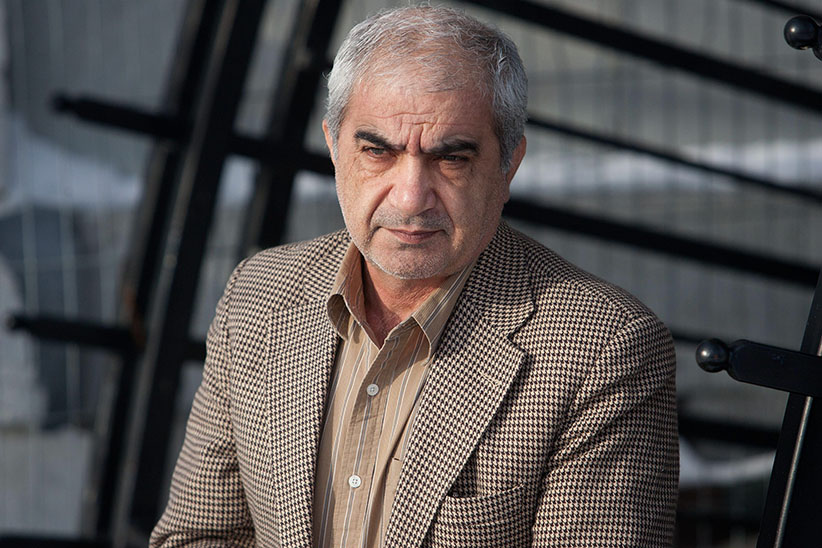

KINGSTON, ON. DECEMBER 5, 2011– Mohammad Shafia (l), eldest son Hamed Shafia and Tooba Mohammad Yahya ( back) exit a police van and are escorted to the Kingston Courthouse on Monday December 5, 2011. He along with his dad and mother are accused of killing the teenage Shafia sisters and Shafia’s first wife in a polygamous marriage over family honour.

MACLEAN’ S PHOTO BY Vincenzo D’Alto

Share

Of all the evidence pointing to his guilt (and there is plenty, by any standard), Mohammad Shafia’s own words—captured on hidden police wiretaps—may have been the clincher for the jury.

“We lost our honour.”

“There is no value of life without honour.”

“Even if they hoist me up onto the gallows, nothing is more dear to me than my honour.”

At the Ontario Court of Appeal on Friday, Crown prosecutor Jocelyn Speyer chose to read for the judges one especially vile intercept, secretly recorded just days after Shafia’s three daughters (and his first wife in their polygamous clan) were found floating in a car at the bottom of a Rideau Canal lock station.

“Even if they come back to life a hundred times, if I have a cleaver in my hand I will cut her in pieces,” Shafia barked on July 19, 2009, speaking to his other wife, Tooba Yahya, and his eldest son, Hamed. “If we remain alive one night or one year, we have no tension in our hearts, [thinking that] our daughter is in the arms of this or that boy, in the arms of this or that man. God curse their graduation! God’s curse on them for a generation! May the devil s–t on their graves!”

Three days later, the immigrant trio was in handcuffs, charged with four counts each of first-degree murder. The alleged motive? The one word Shafia couldn’t stop spewing: honour.

At trial, a jury in Kingston, Ont., completely agreed with the prosecution’s theory: that a multimillionaire Afghan businessman—who moved his children to the freest of countries, settling in Montreal in 2007—conspired with his wife and favourite son to execute three of those children (Zainab, 19; Sahar, 17; and Geeti, 13) because they were “whores” whose “treacherous” conduct destroyed the family’s reputation. Only their deaths, disguised to look like a tragic wrong turn, could restore their dad’s precious honour. (The fourth victim, 52-year-old Rona Amir Mohammad, was a convenient throw-in, long ostracized by her abusive husband and fellow wife.)

All three were sentenced in 2012 to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years.

Four years later, the Shafias are now clawing for a new trial, arguing, among other things, that the original was tainted by the words of a key Crown witness: Shahrzad Mojab, a University of Toronto professor who specializes in honour-based violence. Her testimony reinforced “pre-existing stereotypes of violent and primitive Muslims,” the Shafias’ new lawyers contend, and invited jurors to convict not on proof, but on “cultural prejudice.” (Hamed Shafia has also filed a fresh-evidence application, claiming that newly discovered documents show he was 17 at the time of the crime, not 18 as originally believed, and therefore should have been tried and sentenced as a youth offender.)

On Friday, it was the Crown’s turn to make submissions to the province’s top court. And reminiscent of the trial, the prosecution’s arguments smelled a whole lot more believable than the other side’s.

It was Shafia himself—not professor Mojab—who introduced the concept of honour to the case, Speyer argued. Mojab was called to the stand simply to explain the “context” to a jury of Canadians, who wouldn’t necessarily understand why some cultures equate honour with things that “might seem trivial and inoffensive” (like, for example, having a high school boyfriend). As Mojab explained, some patriarchal cultures measure a family’s honour by the chastity and obedience of its females, and even the mere perception of premarital sex can trigger murder. “The shedding of blood is the way of purifying the name of the family in the community,” she told the court. “It is an expected act.”

Her testimony was especially important, Speyer said, because one of the defence team’s core arguments was that no mother, father or sibling could ever commit such violence against their own flesh and blood. “Her explanation of honour allowed the jury to assess those conversations and understand them in a way that they otherwise would not have been able to do,” she argued. “This is not cultural profiling. This was equipping the jury to understand an issue in the trial.”

In fact, Speyer noted, Mojab went to great lengths to point out that many people in Afghanistan do not condone honour-based violence, and that her testimony shouldn’t paint every Middle Eastern man with the same brush. She was also never asked specifically about the Shafias; her role was to educate the jury about notions of honour, not weigh in on whether this particular case was an honour killing.

“The best evidence that the killings were motivated by honour comes from Shafia himself,” Speyer continued.

Then she read out the transcript of that wiretap. I will cut her in pieces. God curse their graduation. May the devil s–t on their graves! (For the record, Shafia has tried to explain what he meant by that last sentence, as if the words aren’t clear enough. “To me, it means the devil would go out and check with them in their graves,” he testified, back in December 2011. “If they have done a good thing, it would be good. If they did bad, it will be up to God what to do.”)

As for Hamed’s sudden insistence that he was 17 when his sisters turned up dead, the Crown said there is “a substantial body of reliable evidence” that proves otherwise. Hamed has produced three documents to bolster his claim: an old “tazkira,” the official Afghan identity document, which says he was born on Dec. 31, 1991, not 1990 as previously believed; a “Certificate of Live Birth” from Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health, which provides the same date of birth; and a document from the Ministry of Interior Affairs, which is essentially a translation of the tazkira.

But prosecutors say they have their own Hamed documents that clearly contain a 1990 birthday, including two other Afghanistan birth certificates: one issued in 1996, another in 2004. There’s also this obvious problem: the three Shafia children born immediately after Hamed—including dead sister Sahar, and two other surviving kids who can’t be named because of a court-ordered publication ban—arrived in consecutive years: 1991, 1992 and 1993. Simply put, if Hamed’s age is wrong by one year (i.e. if he was really born in 1991), then the other three children are also one year younger than assumed.

In the end, Speyer said, this case ultimately rests on the “overwhelming” physical evidence. The Google searches (“where to commit a murder”). The shards of headlight found at the canal’s edge (proving that one family vehicle, a Lexus SUV, pushed the other, a Nissan Sentra, into the water). The fact that the Sentra’s ignition was turned off when police hoisted the car from the canal. “It’s hard to know how a car can drive into anything with the ignition off,” Speyer said. “The evidence at the scene was completely inconsistent with the accident theory.”

Even if there were some legal errors during the trial, as alleged by the Shafias’ lawyers, Speyer said they were so insignificant that they wouldn’t have altered the eventual verdict. The jury still would have found them all guilty, she said.

And the jurors still would have heard those damning wiretaps.

“They messed up,” Shafia told Tooba in another intercept, discussing his dead daughters yet again. “There was no other way … They committed treason from beginning to end. They betrayed kindness, they betrayed Islam, they betrayed our religion and creed, they betrayed our tradition, they betrayed everything.”

The appeal court has reserved judgment.