Move over, mushers: A battle brews over sled dog parking in Iqaluit

A plan to take away Iqaluit’s only prime sled dog lot has mushers up in arms and fearing for their future

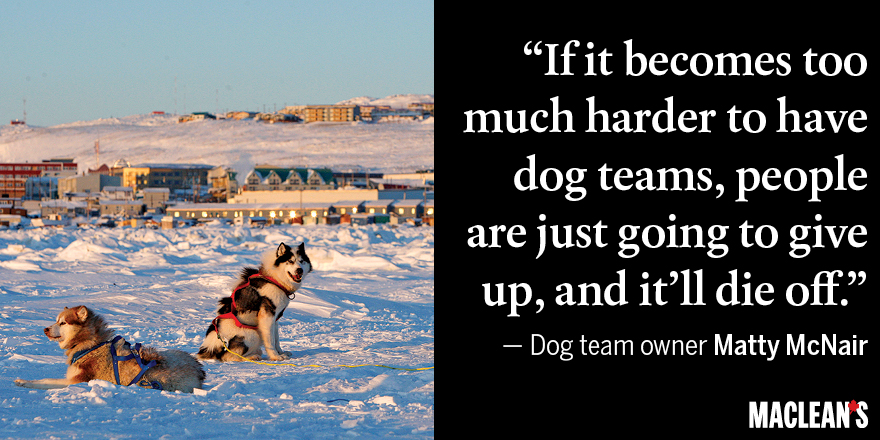

Sled dogs rest on the frozen Frobisher Bay where the G7 finance ministers’ meeting will take place in Iqaluit, Nunavut February 5, 2010. REUTERS/Chris Wattie (CANADA – Tags: BUSINESS POLITICS ANIMALS) – CREDIT: Chris Wattie/Reuters

Share

In Nunavut, the centuries-old practice of dogsledding is as iconic as the mighty walrus, the inukshuk stone landmark and Liberal leaders named Trudeau traipsing across the snowy plains in pillowy parkas. Yet the future of dog-powered transportation in Iqaluit is threatened, enthusiasts say, because officials in Nunavut’s capital city will soon yank what amounts to their dog parking spaces from under their paws.

For more than 20 years, Iqaluit’s mushers have housed their teams on a parcel of land located directly south of Iqaluit’s lone runway. Here, the owners of Iqaluit’s 10 dog teams performed the messy but rewarding work of maintaining about 100 of what the Canadian Kennel Club refers to as “Canadian Eskimo dogs” (locals prefer the more politically correct “Inuit dogs”), 365 days of the year. The area is one of three city plots marked by a municipal sign warning visitors that the dogs, who consume upward of a kilogram of raw meat a day, “should not be considered domestic animals.”

“It’s an ideal location,” says Matty McNair, a Pennsylvania-born adventurer who has called Iqaluit home for 25 years. “You don’t have to run your dogs through the street, because it’s out of town. It’s next to a plowed road, with access to trails and hunting grounds. The dogs used to be behind people’s houses and all over the place.” Mushers say other designated lots are too small and too far from trails, given their locations in town.

But various levels of Nunavut governments, as well as its airport authority, have other plans for the lot. The airport will soon add a second runway as part of a major expansion, which will necessitate the building of a new asphalt plant—to be built exactly where the dogs currently eat, sleep and run. McNair and other mushers say there is nowhere else big or accessible enough to accommodate the large, rambunctious beasts who have the work ethic of Clydesdale horses.

“If it becomes too much harder to have dog teams, people are just going to give up, and it’ll die off,” McNair says. “They are historic. Pick up any brochure of Iqaluit and you’ll see pictures of dogs.” (A picture of McNair’s own dog team is featured on Iqaluit’s tourism website.)

Iqaluit’s mushers began using the land near the airport in the mid-’90s, lured by its flat, remote location. In 2001, then-mayor John Matthews brought in a bylaw allowing for sled-dog parks, though, for mysterious reasons, the land around the airport was never included in the designation.

Further complicating the issue is the matter of the land’s ownership. Officially owned by the government of Nunavut, it is the subject of a (as yet unfulfilled) land-swap agreement with the city. Although the swap is expected to go through, the city can’t designate any of the land to the mushers—and it remains unclear whether there is even the political will to do so.

“Is the city going to offer land? I don’t know,” says John Mabberi-Mudonyi, Iqaluit’s acting chief administrative officer. “That will be a decision of council. They’ve been squatting on that land. Historically, when it comes to sled dogs, everyone thinks of the North. Yes, it’s important to the image of Iqaluit, but should we jump just because [dog owners] want this?”

Finding a place to park dogs is a unique sign of Iqaluit’s growing pains. The city grew by just over eight per cent, to 6,699, between 2006 and 2011, according to Statistics Canada. Its airport, built in 1942 for use by the Canadian and American militaries, was once in the barren plains outside of town; today, businesses and residences encroach on the runway—and the dog run.

Recently, mushers began getting noise complaints about the dogs from the new apartment buildings nearby. Once an essential part of the North’s supply chain, sled dogs have long been replaced by snowmobiles. “You don’t have to feed a snowmobile in the summer,” McNair says.

Dogsledding is now the weekend passion of a handful of Iqaluiters and scores of Arctic tourists, who flock to Iqaluit for the experience of strapping oneself to a pack of eager animals (a four-hour ride typically costs upward of $250). “There’s a romance to dogsledding. Running with dogs is silent; all you hear is the cracking of the sled over snow,” McNair says. “You steer by voice and hope they turn. And they don’t run fast—unless you fall off when they see a caribou.”