The end of Alberta exceptionalism—well, the part Jason Kenney never cared for

The UCP government’s new budget suggests Albertans must accept services that are average by Canadian standards. Will they stand for it?

Travis Toews, Alberta’s finance minister, shows off his budget boots the day before delivering the province’s annual fiscal roadmap (Jason Franson/CP)

Share

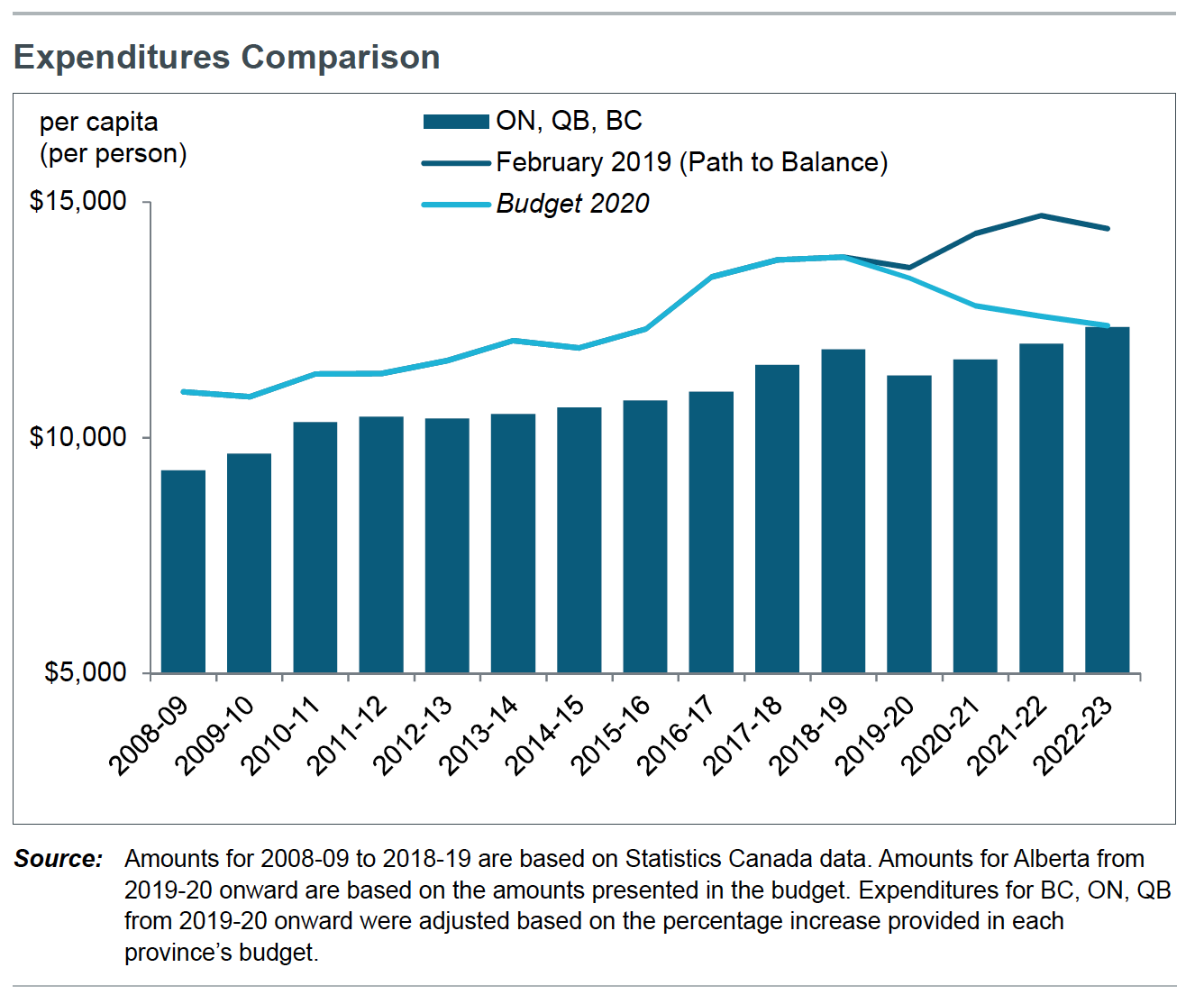

There’s a chart, near the front of Alberta’s 2020 budget, that compares the province’s program spending to averages of Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. It’s tracked higher by about $2,000 per person for more than a decade, but bends down in the new, Jason Kenney-led era until the lines are projected to meet in the 2022-2023 fiscal year, at around $12,350 per capita.

O, glorious future the budget foretells! When Alberta is not only supposed to balance its budget, but it also falls into line on spending with the other big provinces. Alberta exceptionalism, gone at last.

Hold on a second, you might say, if you’ve been following Alberta politics for the last, oh, two generations. The province of extreme flatness (prairie) and bumpiness (Rockies) has long fancied itself the rightful owner of all the superlative boasts: largest economy, highest incomes, lowest tax rates, and—though sometimes Conservative leaders were too bashful to talk about it—the richest and most generous public sector, with competitive pay for doctors, nurses and teachers struggling to keep up with the petroleum engineer and pipefitter Joneses.

Five years after the oil boom came crashing down, those superlatives remain in place. The province is still more prosperous in basically every respect, even if the gaps have narrowed, while Kenney’s Conservatives bank on their promise of economic recovery to further extend Alberta’s dominance. But that whole plan only works, this government has decided, if the province’s public sector is knocked back down to the middle of the pack.

“Alberta can no longer afford to be an outlier in the nation,” Finance Minister Travis Toews said in his budget speech, but he was referring to the public sector’s size and compensation. His fiscal plan does similar griping about overall health spending relative to others, and post-secondary grants per student; it points out to potentially ungrateful seniors and Albertans with disabilities that, while their benefits no longer keep pace with inflation, they are tops, or almost, tops in Canada.

Politicians—at least the ones without tin ears—don’t dare try to comfort frustrated Albertans by saying they should be happy their average incomes are still the highest in Confederation. Those who’ve lost six-figure oil patch jobs and have had to settle for lower (yet still above-average) incomes must nevertheless must make difficult changes, downsizing their lives to the new reality.

RELATED: Jason Kenney’s convenient blueprint to fix half of Alberta’s fiscal house

So it is, too, for households who have suffered cuts to Canada’s most generous seniors’ drug program in Kenney’s budget last fall. Or people who will lose subsidies for wheelchairs or orthopaedic supports in a fresh cut to Alberta’s “special needs” grants for seniors. The government rationalizes this because that “is a unique program, with no comparable programs in other Canadian jurisdictions.” But it’s the sort of spending Alberta was long proud to be able to provide. This government insists it can no longer support such funding, with natural resource royalties still down substantially from five years ago. A conveniently commissioned blue-ribbon report last fall—which disparagingly compared Alberta’s spending levels to those in less wealthy jurisdictions—also argued that the province’s largesse doesn’t always produce best-in-class results.

Alberta will eliminate another 1,400 public sector jobs this year, its master agreement with doctors has been unilaterally ripped up and redrafted in much leaner terms. And there is no money set aside to give unionized staff pay increases—even while the budget optimistically projects steady growth in average weekly wages overall for the first time since pre-bust days. In this respect, Alberta’s leaders have concluded, the best is no longer the aspiration. “We would be spending $10.4 billion less every year if our per capita spending simply matched the average of British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec,” Toews’s speech states.

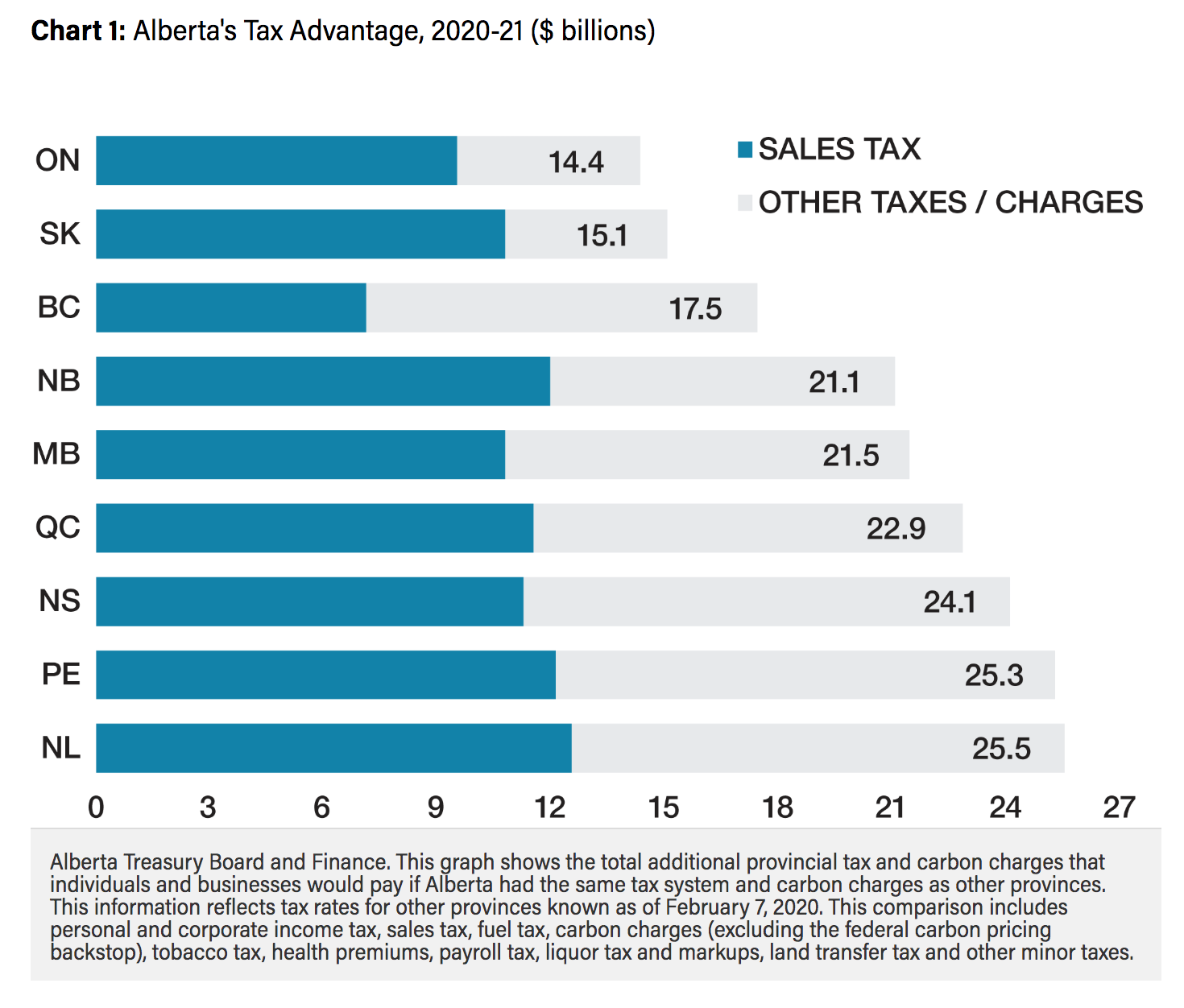

But wait. Isn’t there another side of a budgetary ledger? Ah, yes. According to another chart in the document, Alberta would reap at least $14.4 billion in extra income if its tax rates and programs matched those of Ontario, the second-least-taxed province in Canada. It would have $22.9 billion more if it had Quebec-level taxes. This chart is titled “Alberta’s tax advantage.” The province is on a multi-year plan to slash its corporate tax rate to eight per cent, several points below any other province’s, foregoing extra spending room and instead hoping the discount stokes more private-sector investment.

Then there’s an odd and previously unheard-of page in the budget called “Who Pays Alberta’s Personal Taxes,” which notes how much of the burden is carried by Alberta’s wealthiest—an unsubtle suggestion the Conservatives are seriously eyeing tax cuts for the rich.

A premier and their cabinet are free to choose what sort of exceptionalism they want. Alberta governments used to want it all, but Rachel Notley’s NDP was willing to cede the advantage on taxes, and Kenney is throwing in the towel on the greatness of Alberta’s services. The thing is, Albertans may still want it all. Receiving average—or average-priced—services means asking them to accept less than they’re used to. And scraping toward balanced budgets on the spending side will ultimately mean scraping away quality.

Selling Albertans on the average, not the exceptional: have fun with that, Conservatives.