Trying to figure out the elusive Omar Khadr

If a judge approves bail and sets him free, Canada’s most polarizing prisoner will prove someone wrong

Share

Spend enough time in courtrooms, and they will inevitably appear: students on school field trips, shuffling inside to witness the wheels of justice up close. On Wednesday morning, the second day of Omar Khadr’s bail hearing, it was a small class from Edmonton that walked through the door. The kids were maybe 13 or 14, not much younger than Khadr when he learned to build improvised explosive devices.

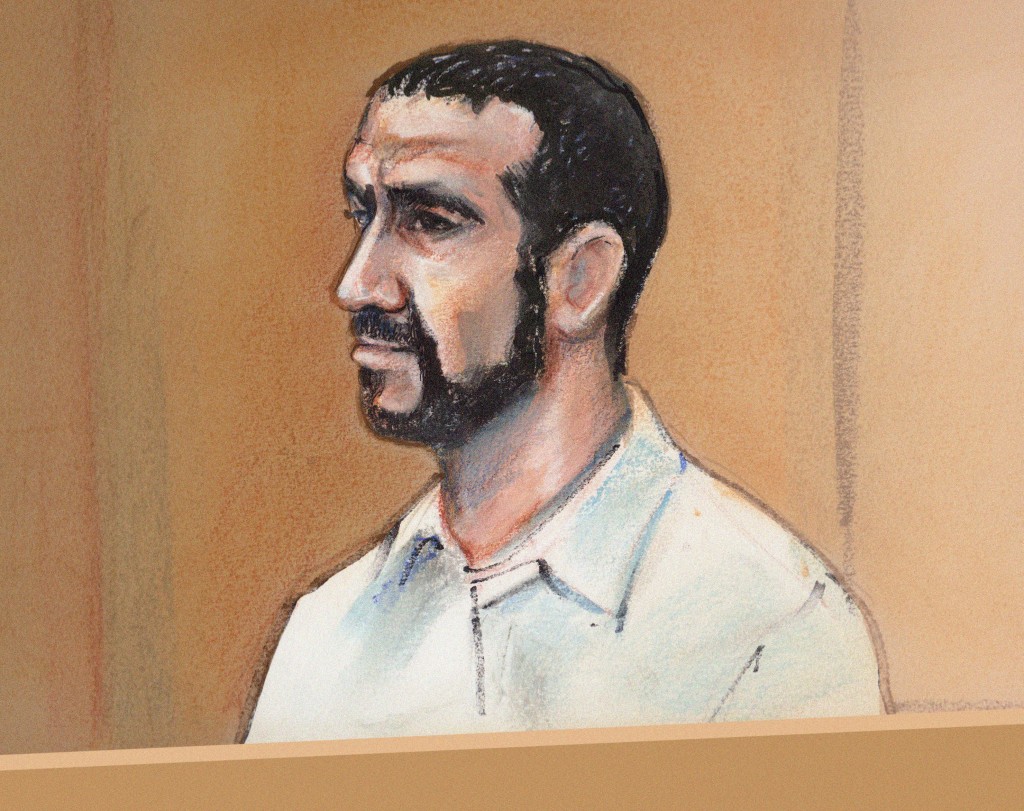

Now 28—six-feet plus, with a short beard and a solid build—Khadr looks nothing at all like the high school visitors he once resembled. Nothing like the teenager who was shot and captured on an Afghanistan battlefield in 2002. Nothing like the teenager who provided a false name to his U.S. interrogators (Akhbar Farhad). Nothing like the teenager who was transported to a different jail cell—every three hours for 21 days, otherwise known as the “frequent flyer program”—to soften him up for a Canadian bureaucrat who had come to question him at the Guantanamo Bay prison camp.

He is a man now. A very divisive, polarizing man whose case has so enraged fellow Canadians (for very different reasons) that even basic facts have become points of debate.

Khadr’s Canadian father, Ahmed Said, was a senior al-Qaeda associate, eulogized as a “founding member” of the terror network after his death at the hands of Pakistani forces (in a 2003 shootout that left another son paralyzed). Osama bin Laden did attend his older sister’s wedding (the same sister who later mourned bin Laden’s death on her Facebook page, asking Allah to “give us the saber and the strength to carry on the fight.”) And Omar did, at the tender age of 15, bury IEDs in post-9/11 Afghanistan, hoping they would find the feet of coalition troops.

After that, the truth is in the eye of the beholder. Believe what you must.

The American government says Khadr was a willing, committed jihadist who bragged about his role in that now-infamous firefight and admitted to tossing the grenade that fatally wounded Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Speer. Khadr and his lawyers say he was an innocent child soldier thrust into armed conflict, and later tortured and tortured until he confessed to whatever his captors wanted to hear.

In 2010, Khadr agreed to plead guilty to five offences at a U.S. military commission, including “murder in violation of the laws of war,” and signed a detailed stipulation of fact laying out his terrorist activities. Khadr and his lawyers now say those facts are fiction, that he didn’t throw a grenade at anyone, and that he only signed the deal so he could escape Gitmo and serve the rest of his eight-year sentence in a Canadian prison.

The Harper government says (even when not asked) that Khadr was convicted of “heinous crimes” and it will “vigorously defend against any attempt to lessen his punishment” now that he’s serving his sentence in Canada. Khadr and his lawyers say he is a victim of cheap politics, and is anxious to prove that he’s a peaceful, grateful citizen who deserves a second chance (and $20-million in damages from taxpayers.)

And so on and so on. Such is the Khadr narrative, 13 years after it all began: convenient assertions dripping with disclaimers.

His high-profile bail application, now in the hands of a judge, is no different.

In November 2013, with Khadr safely back on home soil, his legal team requested an appeal of his U.S. convictions at a special review court in Alexandria, Va. Simply put, they contend that Khadr can’t be guilty of the offences on his rap sheet because those offences didn’t exist in 2002; the Bush White House drafted the war-crime definitions after Khadr was apprehended. And even if Khadr did kill Sgt. Speer, they argue, it wasn’t a war crime. It was war. (For the record, Khadr is the only enemy fighter to be convicted of a soldier’s death in either the Iraq or Afghanistan combat zones.)

With his appeal now pending south of the border, Khadr wants an Edmonton judge to release him, on bail, from his current home at Alberta’s Bowden Institution, a medium-security prison. Convicted criminals request such relief all the time, and it’s regularly granted. But like all things Khadr, there is nothing typical about this application.

Here’s the wrinkle, according to the federal government: Khadr was flown to Canada from Cuba in 2012 under the authority of both a longstanding treaty with the U.S. and the International Transfer of Offenders Act (ITOA). But the Act specifically states that such transfers are available only to Canadian convicts, serving time in foreign prisons, whose sentences are final. If an appeal is active, in other words, a transfer can’t happen. “When he was transferred, it was with the idea that he would not appeal, that he would not seek to collaterally attack his sentence,” Bruce Hughson, a federal lawyer, told Madame Justice June Ross. “That is why the transfer was granted.”

If bail were now approved, Hughson said, it would be “a direct violation” of the plea deal—and could be frowned upon by the U.S. government, which only agreed to send Khadr home on the condition that Canada administer the sentence exactly as delivered. At the very worst, he said other countries could start thinking twice about allowing Canadian prisoners to go home out of fear that their sentences might be shortened.

Nathan Whitling, who has represented Khadr for more than a decade, said he doubts the U.S. “would somehow sever its relationship with Canada” if Khadr wins bail. He is, after all, not asking a Canadian court to overturn the U.S. sentence; he is simply asking for bail—“a right that every other prisoner in this country has”—while an American court ponders his convictions.

It is Ross who will now do the pondering. Does she have the legal authority to grant Khadr bail? And if she does, is he a good candidate for release? “It is not a surprise to anyone that I am reserving my decision on this matter,” she told the lawyers, just before adjourning. “I will give this a high priority and get to it as quickly as I can. It’s a big job, though, and I will take the time that I need to take on it.”

If she approves bail, another hearing will be held to determine the release conditions, if any. Dennis Edney, Khadr’s other longtime lawyer, has already pledged to welcome Khadr into his Edmonton home and treat him like a member of the family. If bail is denied, his next chance at freedom will come in three months, when he appears in front of the Parole Board of Canada in June. (The prisoner transfer treaty does allow him to seek parole.)

And if parole is denied? Khadr’s sentence will officially expire in October 2018, leaving him a completely free man. But he’s also eligible for statutory release in late 2016, after serving two-thirds of his sentence. In the vast majority of cases, the government doesn’t oppose a prisoner’s statutory release. But most prisoners aren’t named Khadr. “This government has obviously dug in politically in relation to this case, unfortunately,” Whitling told reporters outside the courthouse. “I think it’s lost a lot of its objectivity, so we expect they will dig in and fight against Mr. Khadr at every stage of his sentence.”

Edney went so far as to say that the Harper government is so obsessed with demonizing his client that a member of the Prime Minister’s Office phones Khadr’s prison “every month or so to check” on him. (A PMO source told Maclean’s “there is absolutely no truth to this.”)

Although the bail application hinges on the kind of arcane legal concepts that would confound even the brightest high schooler in the gallery—habeas corpus, transfer obligations, territoriality—the real question is always the same: Which portrait of Omar Khadr is the accurate one?

Speaking to the cameras, Whitling was blunt. Khadr did not kill Sgt. Speer. He “is not a threat to anyone.” He was “convicted of some so-called crimes that were concocted” by the former Bush administration. And if he were stuck at Guantanamo, he would have signed any document the Pentagon presented if it meant going home. “He knows that he’s now in a country with real laws and real courts,” Whitling said. “He is getting a whole lot of support from educators and spiritual leaders and members of his communities and his lawyers, and he’s really quite optimistic about getting out and getting on with his life. He certainly has no anger or frustration or blame toward anyone involved in this process.”

In his own sworn affidavit, Khadr says he just wants to find a job, attend college and learn basic life skills, from grocery shopping to buying a gym membership. He has no idea how to catch a city bus or apply for a library card. But Khadr also doesn’t hide the fact that he plans to have contact with his notorious family, via phone calls and Skype.

“Mr. Khadr is now 28 years old,” Whitling said. “You can’t tell a 28-year-old that he can’t speak to his mother because they might brainwash him or something of that nature. He is an independent-thinking individual. He is now nearly to his high school equivalency. He’s an intelligent person and we don’t have any concern that he is somehow going to be influenced or radicalized by some other people.”

As his lawyers spoke to the media, Khadr was in the back of a locked sheriff’s van, beginning the two-hour drive back to Bowden. Whatever happens—bail, parole, statutory release, sentence expiry—he is now one day closer to walking out of prison.

“He’ll be slowly reintegrated into Canadian society,” Edney said. “This is someone who hasn’t even opened a door since the age of 15. That is the journey he will have to take. He will also get on with his education, and like every other young adult, he’ll have to start to make his own way through life. My belief is he will be a wonderful contributor to our Canadian society.”

Belief, as always, being the key word.