The Supreme Court will decide if two sons of KGB spies can be Canadian

Four years after Ottawa revoked the brothers’ citizenship, the Supreme Court will hear one final appeal launched by the Trudeau government

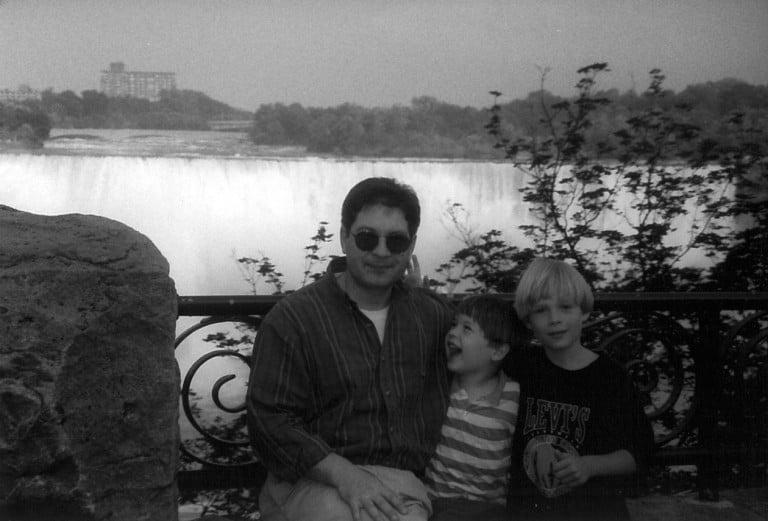

‘Donald Heathfield’ with his sons Alex and Tim in 1999. (Tim and Alex Vavilov)

Share

The Supreme Court will have the final say in the stranger-than-fiction saga of the Vavilov brothers—two men born in Toronto, but famously stripped of Canadian citizenship after their parents were exposed as elite Russian spies operating in the West under stolen identities.

Four years after Ottawa revoked the brothers’ citizenship—and one year after the younger sibling, Alexander, won it back at the Federal Court of Appeal—the Supreme Court announced this morning it will hear one final appeal launched by the Trudeau government. A hearing date will be set in the coming weeks.

The appeal will be heard in conjunction with two other cases that, according to the hight court, “provide an opportunity to consider the nature and scope of judicial review of administrative action.” Although Alex’s case will be the focus of the arguments, the eventual ruling will also apply to Timothy Vavilov, whose separate court challenge on the same legal grounds is not as far along as his little brother’s.

READ MORE: FAQ: Two sons of KGB spies fight for their Canadian citizenship

Today’s announcement is a temporary victory for federal officials, who remain determined to keep the Vavilovs from resettling in Canada. The government says the novel case raises important questions about “the integrity of Canadian citizenship.” The brothers insist they have done nothing wrong, pose no threat to Canada, and have been unfairly denied their birthright in retaliation for their parents’ espionage activities.

The Supreme Court will now decide once and for all.

Featured in a recent Maclean’s cover article, the Vavilovs’ life story has all the elements of a Jean Le Carré espionage thriller. The acclaimed FX television series The Americans, now in its final season, was inspired in part by the same 2010 FBI bust that exposed Tim and Alex’s mom and dad.

Born at Women’s College Hospital in the 1990s—as Tim and Alex Foley—the brothers spent their childhood oblivious to the fact that their parents were a husband-and-wife team of deep-cover KGB “illegals” who slipped into Canada during the Cold War, assumed the identities of two dead babies from Montreal (Donald Howard Heathfield and Tracey Lee Ann Foley) and settled in Toronto, where “Don” built a successful diaper-delivery company.

When Tim was five and Alex was one, the family moved to France, then to Massachusetts, where the spy couple was ultimately arrested and their true identities revealed: Andrey Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova. Tim was 20 when authorities stormed their Boston-area home; Alex was 16. “I was shocked in ways words cannot describe,” Tim later wrote in a sworn affidavit.

BIG READ: The Russian spies who raised us

After the bust triggered headlines around the world, Tim and Alex flew to Moscow, where they were granted Russian citizenship and a new last name. In Ottawa, meanwhile, immigration officials concluded that the brothers were never Canadian to begin with, despite being born here, because their parents were “employees in Canada of a foreign government,” a rare exception to the birthright rule under the Citizenship Act. Now 27 and 23, the Vavilovs have been fighting in court ever since to regain their lost status. “Whether or not the government decides to reissue my citizenship, I will always be Canadian at heart,” Alex told Maclean’s last year. “I have grown up that way and believe it to be my only identity. It is something I would fight to the end to retain.”

Despite all the intrigue surrounding their story, the brothers’ case hinges on a specific line of legislation: the definition of “employee of a foreign government,” as outlined in section 3(2)(a) of the Act. Ottawa contends (and the Federal Court agreed, in 2015) that the clause means exactly what it says: any employee of a foreign government, including a deep-cover Russian spy. But the Vavilovs argue that the meaning is actually much more specific, applying only to those employees who enjoy diplomatic immunity, such as an ambassador. Because their parents lived under assumed names and had no affiliation with the Russian embassy in Ottawa—and therefore no immunity—Tim and Alex say the clause can’t possibly apply to them, making them both legitimate Canadians in the eyes of the law.

In a 2-1 ruling released last June, the Federal Court of Appeal agreed with that logic, reinstating Alex’s citizenship. The government sought leave to appeal in September, leading to today’s decision.

In yet another twist, however, the high court does not appear particularly interested in ruling on that specific citizenship clause. Instead, the Supreme Court says Alex’s case, along with two others—appeals by Bell Canada and the National Football League over whether Canadian viewers can watch U.S. commercials during the Super Bowl telecast—provide an opportunity to clarify a much larger issue: the standard of review courts should apply when evaluating the conclusions of administrative decision-maker. In the brothers’ case, that decision-maker was the Registrar of Citizenship.

In previous court filings, the government has said the registrar reached a reasonable conclusion—that undercover spies are indeed employees of a foreign government—and that the Federal Court of Appeal created an “absurd result” when it overturned that finding. The dissenting judge on the appeal panel also agreed “that it was open to the Registrar to conclude as she did,” and that her decision should stand.

The Supreme Court will have the final say over how courts review such administrative decisions. Either way, a sensational case will come down to a granular question of law.