We printed the names of Canadians killed in the Great War. You gave their stories life.

Here’s how Canadians embraced our project to honour the fallen from the First World War—and how, with each name, our readers imbued history with another soul

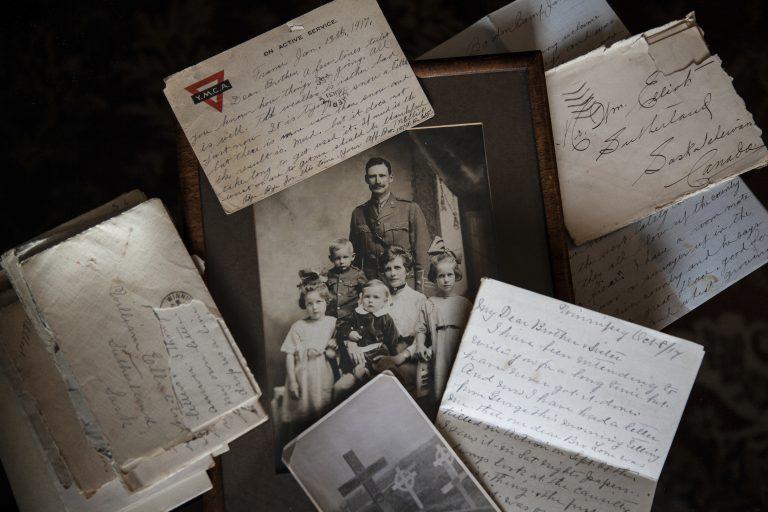

Letters from Thomas Ninian Elliot to his family with photographs of family and the original grave in Belgium. (Elisa Elliot)

Share

When the actor R.H. Thomson was providing narration for one of First World War historian Norm Christie’s documentaries, he told Christie he didn’t understand the point of the cemeteries where the war dead rest. “The cemeteries are the point,” Christie replied.

The 100 years since Armistice was declared have woven the story of Canadian courage, suffering and loss in the Great War into a unified portrait of one young nation’s sacrifice. But it is when you focus on a single name—one face, one life, one gravestone, one family left behind—out of thousands that the full weight of the torch passed to all of us is felt. “Once you get down to the individual, history becomes spiritual,” says Christie.

And so, Maclean’s has published a 100th anniversary First World War commemorative issue with 66,349 individual covers, each one dedicated to one of the Canadian fallen (plus one for the Unknown Soldier). We do this in order to translate the unfathomable enormity of the loss and honour of their service into a human-scale story, to place the name and memory of each of the dead into the hands of one person now living in the world they helped to defend.

From family members to perfect strangers several generations removed, the overwhelming public response to the project has been an exercise in collective memory and gratitude.

Pte. John Ferguson and his wife, Minnie, both went overseas, John with the Canadian infantry and Minnie most likely as a nurse. Near the end of the battle of Passchendaele, Ferguson was killed; his body was never recovered, and his date of death was declared as Oct. 31, 1917. Minnie was pregnant and waiting for him at Folkestone army base in England. Their son John was born in January, three months after his father’s death. Minnie would eventually return to Saskatchewan and remarry, and her grandsons would grow up with only the vaguest notion that their grandfather had served and died in the First World War.

That changed profoundly several years ago, when Library and Archives Canada began making full digitized service records available to the public. Terry Ferguson and his three brothers, all of whom live in Winnipeg, arrived at a new understanding of the war. It was one their dad, John Jr., had been deprived of. “[My grandfather] had been out there and sacrificing so much for all of us, essentially, and paid the ultimate price,” he says. “And really, my family did, because my father grew up without that influence, without that person there. It rippled through us.”

Without realizing it, Terry and one of his brothers both separately ordered commemorative copies of the magazine devoted to their grandfather. Ferguson has changed Nov. 11 for them all. “We always went to the ceremonies and we wore a poppy and stuff, but when we found out how connected our grandfather was and what he had gone through, it changed, and Remembrance Day became personal for us,” Terry says. “It’s pride in a country that went out and fought for what was right. But now it’s pride and almost sadness and remembrance of what they gave up.”

Larry Elliot vaguely recalled his late father mentioning an uncle who died in the First World War, but it wasn’t until he began his own research last year that he plunged into the life of Maj. Thomas Ninian Elliot, killed on Sept. 28, 1917, while serving with a railway battalion near Ypres, Belgium. Exactly 100 years—to the hour—after he breathed his last, Elliot’s descendants gathered last September next to Thomas’s brother’s grave in Saskatoon, paying tribute with a bagpiper and whisky toast to the man whose body lay 6,800 km away under Belgian soil.

Listen to Shannon Proudfoot talk about this project on The Big Story podcast.

Learn more at The Big Story Podcast.

“We honour your immense courage, sacrifice and service to your king and country. We are humbled by the greatest love you have shown,” they toasted. “We have not broken faith.”

When Larry and his family first heard about the tribute covers, their first thought was that they needed to find their soldier among all the dead, but then they realized the impossibility of that. Instead, they have special-ordered copies with his name, and Larry continues to unearth everything he can of his once-obscure great-uncle’s life and service.

In Vancouver, the cover Bryan Fair received launched him into a search for information on the life of a perfect stranger from the opposite end of the country. Fair’s issue was dedicated to Capt. Thomas Malcolm McLean, who died on Aug. 10, 1918, at the age of 23. Fair’s search revealed McLean’s hometown of Bridgewater, N.S., and the names of his parents, so he wrote to the local museum, asking for any crumbs of information they had. Fair is adopted, so tracing this kind of lineage is something he’s not been able to do for himself. “I find it interesting, what motivates people to search their history,” he says. “It’s trying to find a place in the world and trying to find connections with things.”

The Bridgewater museum shared everything they could dig up, and Fair traced McLean’s sister to a small town in Wisconsin. There the trail went cold. “As I read through it, I was thinking of him,” he says of the issue. “I thought, if it’s touching me, if it’s making sense to me, then maybe there’s somebody in his family who would like to have this, because it would mean a lot more to them.” Fair is still working to track down McLean’s descendants.

Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) ordered 20 magazines paying tribute to Sgt. Hugh Cairns, V.C., Canada’s last recipient of the Victoria Cross in the First World War. On Nov. 2, the 100th anniversary of Cairns’s death, VAC held a ceremony in his hometown of Saskatoon, presenting the commemorative editions to Cairns’s descendants and to students at the elementary school named in his honour. At Valenciennes, France, Cairns single-handedly charged enemy positions again and again, even after he had been wounded, before he ultimately collapsed from blood loss. He died nine days before peace was declared and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest honour for bravery in the British Empire.

Before going off to war, Cairns sang in his church choir and loved playing soccer, and he set up his own plumbing business. He was 21 when he died.

Alyssa Gomori is the curator of the Erland Lee Museum in Stoney Creek, Ont., once home to Erland and Janet Lee, whose oldest son, Gordon D’Arcy Lee, began his military career when he was just 16.

By the time Gordon went overseas in 1916, he had attained the rank of captain, and he soon became a major. In October 1916, he wrote to his sister from “somewhere in France in a little bivouac,” saying how the weather reminded him of home. In March, he wrote to his mother, describing the injuries and death all around and signing off with his middle name. Two months later, on May 3, 1917, after fighting at Vimy Ridge and 10 days shy of his 23rd birthday, Lee was killed in action near Lens, France.

He still seems very nearby to Gomori. “I set foot in his house every single day, and I think that I’m going up the stairs he would have gone up to go to bed every day,” she says. “He never came home. It’s a very emotional connection, because you imagine his mother and father being devastated by his loss.”

Gomori had read about the Maclean’s tribute covers, and when she first spotted the issues in the checkout lane at the grocery store, she dropped to the floor to rifle through them, before settling on one dedicated to Pte. Frank Ferguson Thompson, killed on Sept. 7, 1917, at the age of 39. She researched that soldier’s story and special-ordered copies dedicated to Lee. “A lot of people who died that long ago, unless someone is a genealogist in their family, their names don’t get mentioned,” she says.

Many people who wrote to Maclean’s to order a copy felt compelled to include everything they knew about the service member whose cover they sought—photographs, data, anecdotes, eulogies. Emails arrived heavy with attachments; phone calls were long and animated. It was as though they just needed someone to know more about that one person lost, who loved and was loved, among the 66,349.

Each edition of the Maclean’s First World War Centennial Issue featured the name of one of the 66,349 servicemen and women who sacrificed their lives. Since publication, many Canadians have contacted us, sharing the name featured on their cover or inquiring where a particular cover ended up. As we approach Remembrance Day, we’re asking readers to share the cover that they received with the hashtag #WeRemember100.