The bravery and the tragedy of Shannen Koostachin

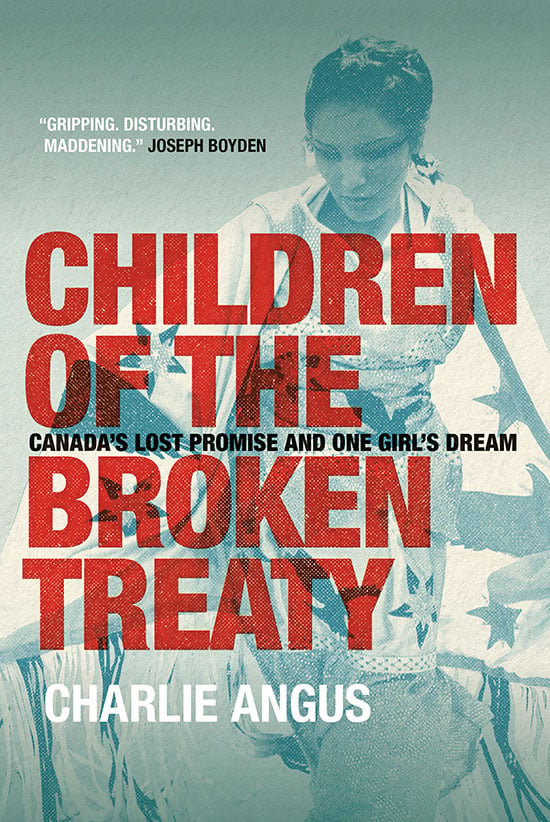

She inspired a film, and even a DC Comics hero. An excerpt of MP Charlie Angus’ new book about the 13-year-old who helped launch a national campaign.

Shannen Kootaschin speaks on Parliament HIll. (Charles Dobie)

Share

Before the water and housing crises in Attawapiskat, Ont., before its chief, Theresa Spence, held her hunger strike, the Cree First Nations community near the shores of James Bay faced an educational crisis. Its primary school was shut in 2000 because of site contamination and health issues from a 1979 diesel fuel leak. Despite federal government promises of a new school, students were still in mould-contaminated portables seven years later when they learned that Ottawa had cancelled the project. The news sparked a rebellion among Attawapiskat youth who reached out to students across the country, inspiring the largest youth-driven rights campaign in Canadian history.

Before the water and housing crises in Attawapiskat, Ont., before its chief, Theresa Spence, held her hunger strike, the Cree First Nations community near the shores of James Bay faced an educational crisis. Its primary school was shut in 2000 because of site contamination and health issues from a 1979 diesel fuel leak. Despite federal government promises of a new school, students were still in mould-contaminated portables seven years later when they learned that Ottawa had cancelled the project. The news sparked a rebellion among Attawapiskat youth who reached out to students across the country, inspiring the largest youth-driven rights campaign in Canadian history.

The campaign’s public face, a charismatic 13-year-old girl named Shannen Koostachin, eventually became widely known. She was nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize, and inspired a documentary, a novel and even a character in DC Comics’ Justice League. NDP MP Charlie Angus, whose Timmins–James Bay riding includes the reserve, has written an account of that struggle that is at once historical, political and deeply personal—Shannen lived with Angus and his family for a year while attending school.

In May 2008, Attawapiskat’s Grade 8 class came to Ottawa, for the National Day of Action for Indigenous People and to meet with Indian Affairs minister Chuck Strahl. In this exclusive excerpt from Children of the Broken Treaty: Canada’s Lost Promise and One Girl’s Dream, Angus—who was on Parliament Hill in support of the Indigenous activists—watches as Shannen steps into the national spotlight.

An exclusive excerpt of Children of the Broken Treaty follows.

The meeting with Strahl was set for the morning, just prior to the national march of Indigenous activists and supporters. The plan was for the youth leaders—Chris Kataquapit, Solomon Rae, and Koostachin—to speak to Strahl about the conditions that they faced, and then Grand Chief Stan Louttit would lay out options for getting the school project back on track.

Louttit spoke with the three youth to prepare them for what was to come. “Speak from the heart, and speak the truth, and you will be fine,” he said to them. The delegation was then ushered into a large, plush room with rich cornice mouldings. To break the ice, Strahl pointed to the surroundings and asked, “What do you think of my office?”

Shannen didn’t miss a beat. “I told him I wished I had a classroom that was as nice as his office that he met in every day.”

As they sat down, Strahl pre-empted the discussion by telling them matter of factly that the school wouldn’t be built. It simply wasn’t on the government’s list of priorities. The delegation was stunned. What was the purpose of the meeting if the government refused to discuss options?

“We invite you to come to our community to understand our living situation,” Chris Kataquapit offered.

But the answer was no.

The elders began to cry. Shannen didn’t want to cry in front of the government, so she stormed out. Louttit went out into the hall to find her. “This is not how the meeting ends,” he told her comfortingly. “You need to go back in there and be a leader.” Shannen wasn’t just sad but also furious. Nonetheless, she listened to him.

As she stepped back into the room, Strahl was telling the delegation the meeting was over. And this is how she later retold the story to media and supporters: “He told me he couldn’t stay for more of the meeting because he had other things to do. We were very upset. The elders who were with us had tears in their eyes . . . But when he was about to leave, I looked at him straight in the eyes and said, ‘Oh, we’re not going to quit, we’re not going to give up!’ ”

The delegation came out of the meeting into a bank of media cameras. They were whisked into taxis to meet the rest of the students joining the march assembling on Victoria Island. It was a fairgrounds atmosphere as thousands of people prepared for the big protest march. As soon as the rest of the Attawapiskat students saw the delegation, they knew that something was wrong. The leaders looked tense, and the youth representatives were clearly stressed. Around them, marchers bustled and shouted excitedly for the rally to begin, but the students of Attawapiskat stood in the midst of the crowd, bereft and desolate.

Carinna Pellatt, a teacher from Attawapiskat, said that the students were determined not to cry in public: “We stood in that circle, and the elders were crying. I cried. But the students were so stoic. I always wondered why the minister agreed to meet them if he was just going to turn them down.”

As the Attawapiskat students tried to come to terms with what had just happened, students from Brampton, Ont., who had come in support, stood with them. Pellatt said that their presence had a profound effect on the Attawapiskat youth: “When the students from St. Edmund Campion came to be with them, it really meant a lot. Both groups of students were shy, but words aren’t necessary with the Cree. Just to know that students came to be there with them meant so much.”

Strahl later told the media that he had simply been honest with the youth. “I could have strung them along. But they have been strung along before.”

Walking up to Parliament Hill, the leaders were troubled by how things had turned out. These were still early days for the new government, but clearly Harper’s team was not responding the way previous governments would have to the bad publicity of being perceived as so hard-hearted toward First Nations children. The Harper government had been pushed on the issue and they pushed back hard. The government was likely to dig in on the school campaign, and the momentum of the entire movement appeared to be in jeopardy. The question we asked ourselves was what effect would this rejection have on the students? Was it fair to bring children down from James Bay only to have their hearts broken?

As we approached Parliament Hill, the rally organizers informed us that they would allow one of the young people from the delegation to speak. This was a moment to try to salvage something from what had been a very heartbreaking day. It was decided that Shannen would be the one to tell what had happened in the meeting with Strahl. When she was informed that she would be the voice for the community, she seemed panic-stricken. “I don’t have my speech with me. I lost my notes. I don’t know what to say.”

“Shannen,” I said, “this is the moment where you need to be heard. Just speak from the heart. You’ll know what to say.”

The youth stood on the steps of Parliament as one First Nations leader after another denounced the government. Shannen had her hair pulled back in a ponytail and seemed to be so small and so young as she stood beside these national leaders. She was shaking with nervous energy. She and her classmates were just 13-year-old kids from an isolated reserve who were now standing in the midst of a complex political struggle that stretched back generations.

One of the adults whispered to me, “Do you think she will be okay? What do you think she’s going to do?”

“I have no idea,” I replied, “but we’re about to find out.”

When the time came, the rally organizers announced that the youth activists from Attawapiskat were on Parliament Hill, and a huge cheer went through the crowd. Shannen stepped forward to the microphone, and immediately the nervous, frightened girl became very poised.

“Hello, everybody, my name is Shannen Koostachin, and I am from the Attawapiskat First Nation. Today I am sad because Mr. Chuck Strahl said he didn’t have the money to build our school.” She paused and then added, “But I didn’t believe him.” The crowd lit up. Shannen became more confident. She related the story of looking him in the eye and telling him that the children were not going away. “And,” she said, “I could tell he was nervous.” The crowd roared their approval.

It was a simple speech, but her heartfelt determination genuinely touched people. The news coverage across Canada became the story of the 13-year-old girl who had never seen a real school and had stood up to the minister of Indian Affairs. Speaking to the media afterward, she related the daily humiliations of being educated in substandard conditions. “I told [Strahl] that we will not quit until every First Nation child has a school that they are proud of, that they can call their own.” In terms of the political impact, Shannen hit it out of the ballpark.

The day had been a hard one for the students. But there were those present who saw Shannen’s two-minute speech on the Hill as a potential breakthrough moment. In what would be a nasty and long-term fight with an entrenched government, the Attawapiskat School campaign now had a face and a voice.

Shannen Koostachin was killed in a car accident before her 16th birthday in 2010. The campaign for Indigenous education, renamed Shannen’s Dream, continued. Eventually, Ottawa agreed to fund a new school, which opened on Sept. 8, 2014.

Excerpted by permission from Children of the Broken Treaty by Charlie Angus. Copyright © 2015 Charlie Angus. Published by University of Regina Press. All rights reserved.

Excerpted by permission from Children of the Broken Treaty by Charlie Angus. Copyright © 2015 Charlie Angus. Published by University of Regina Press. All rights reserved.